|

New

Releases |

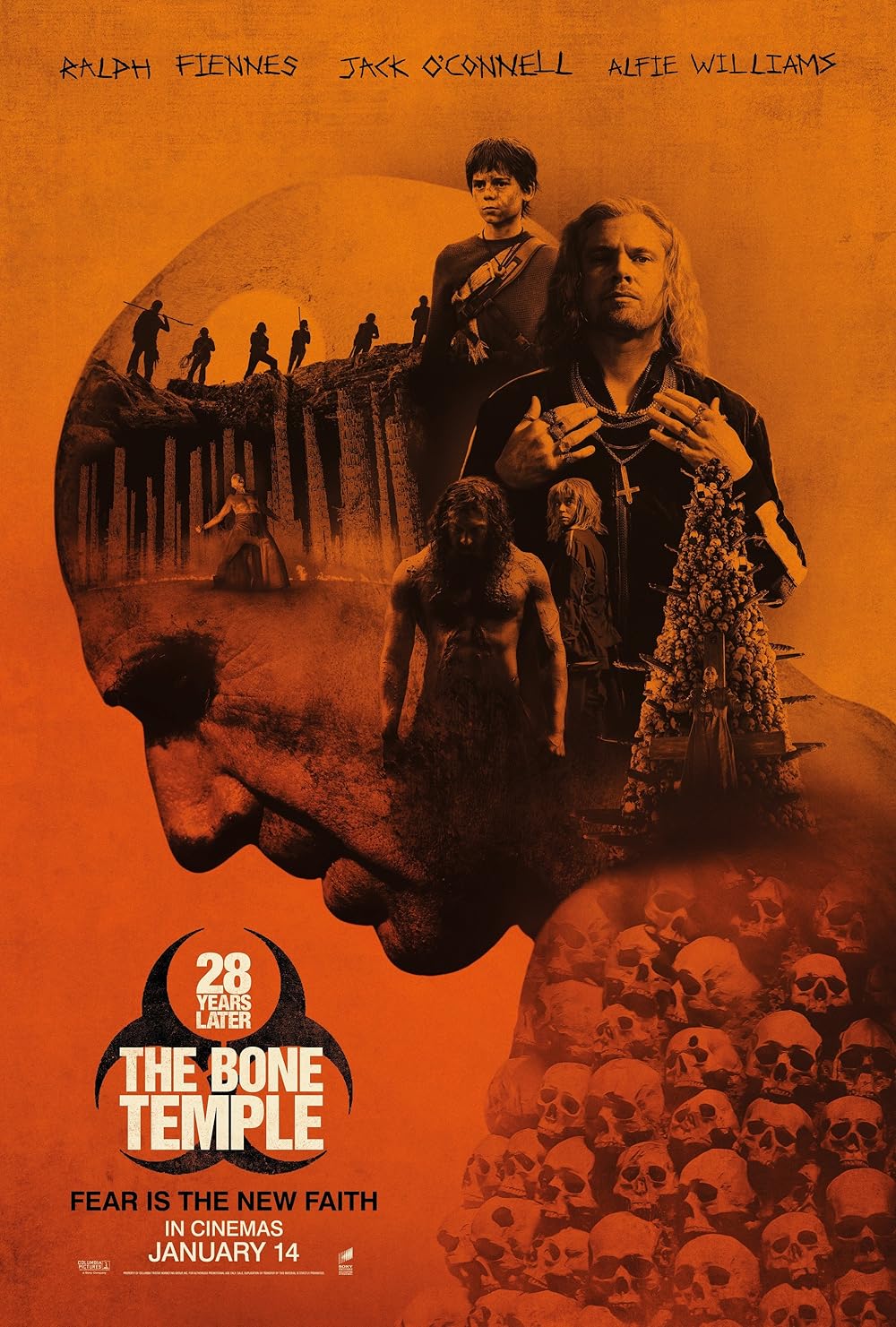

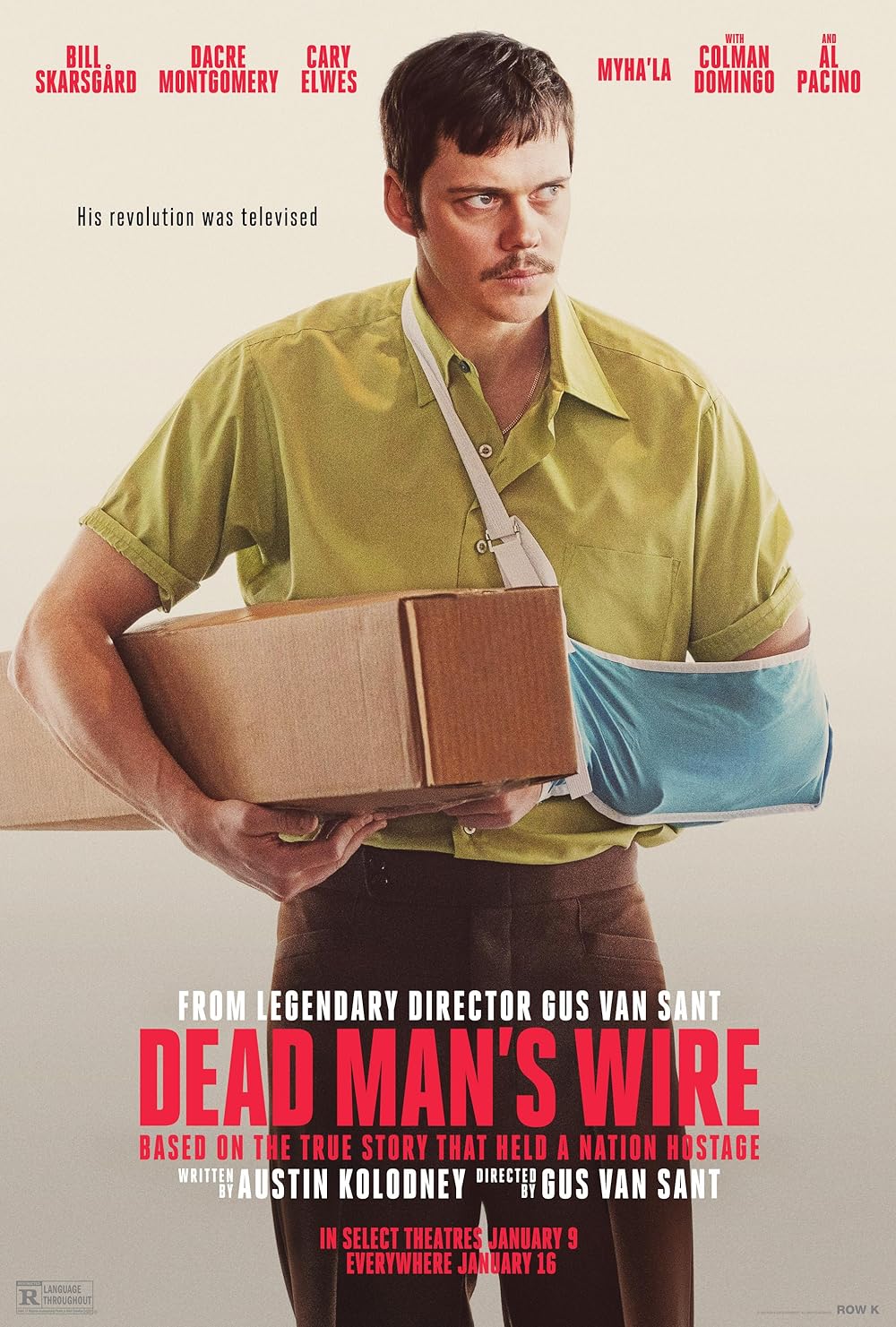

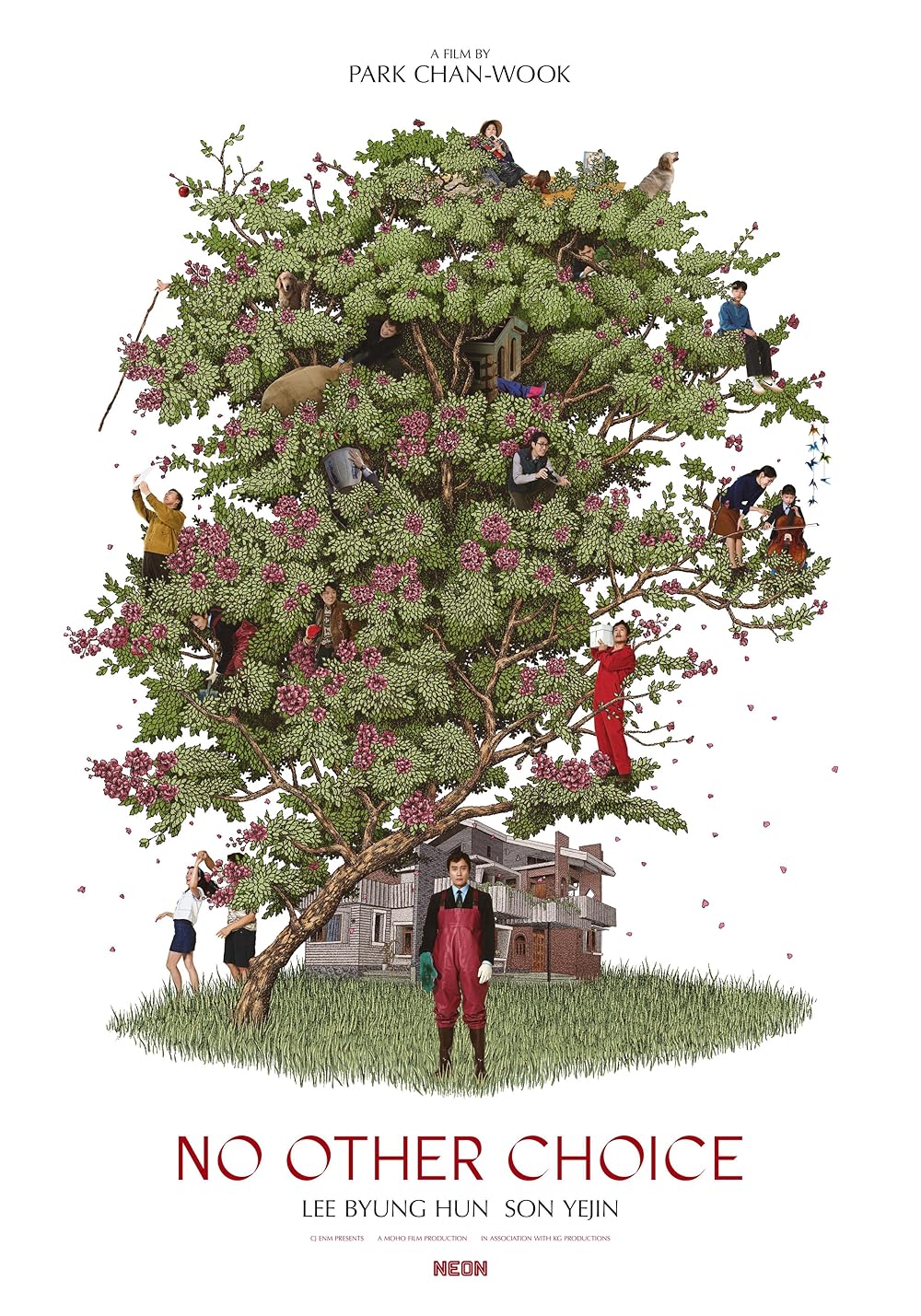

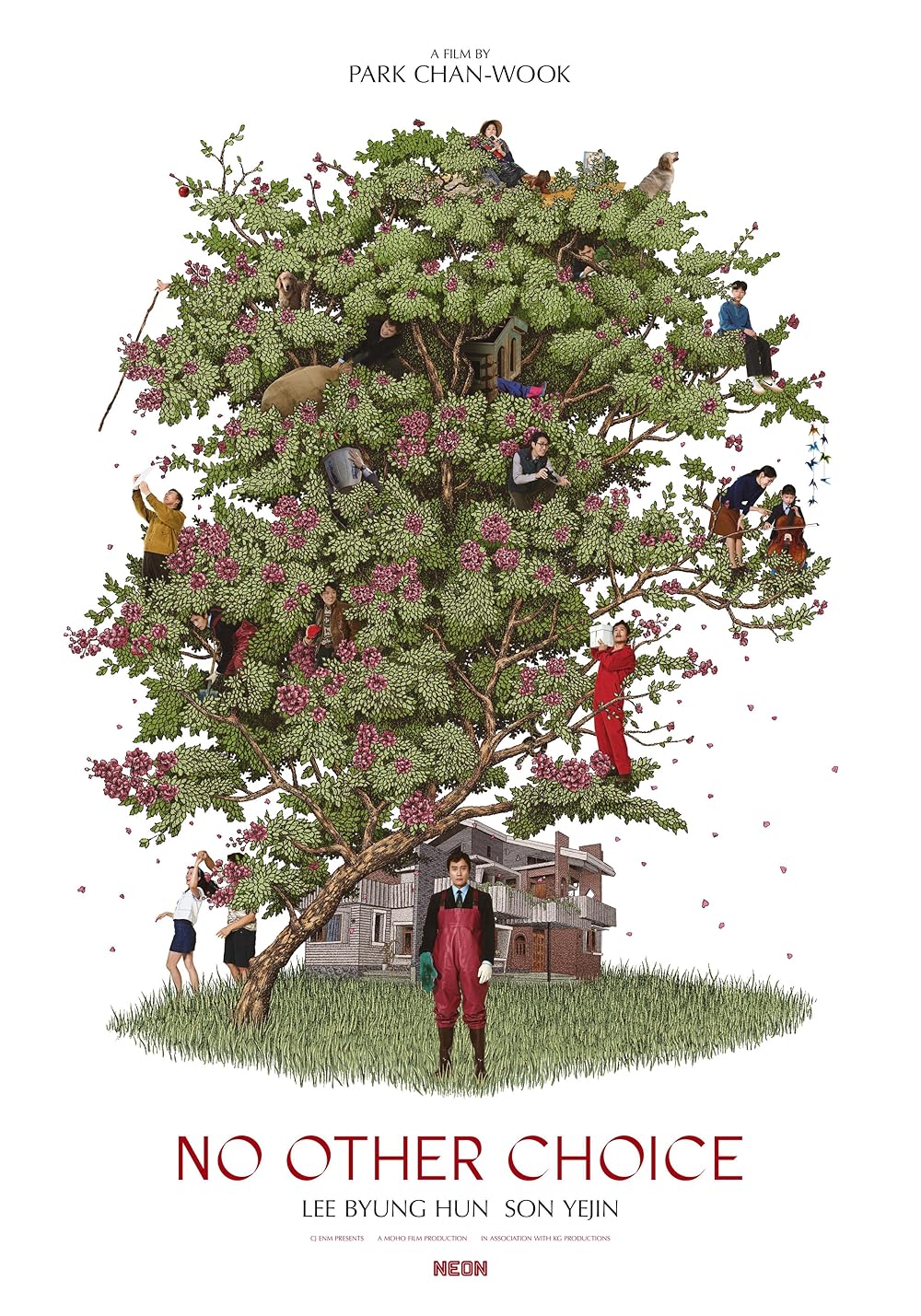

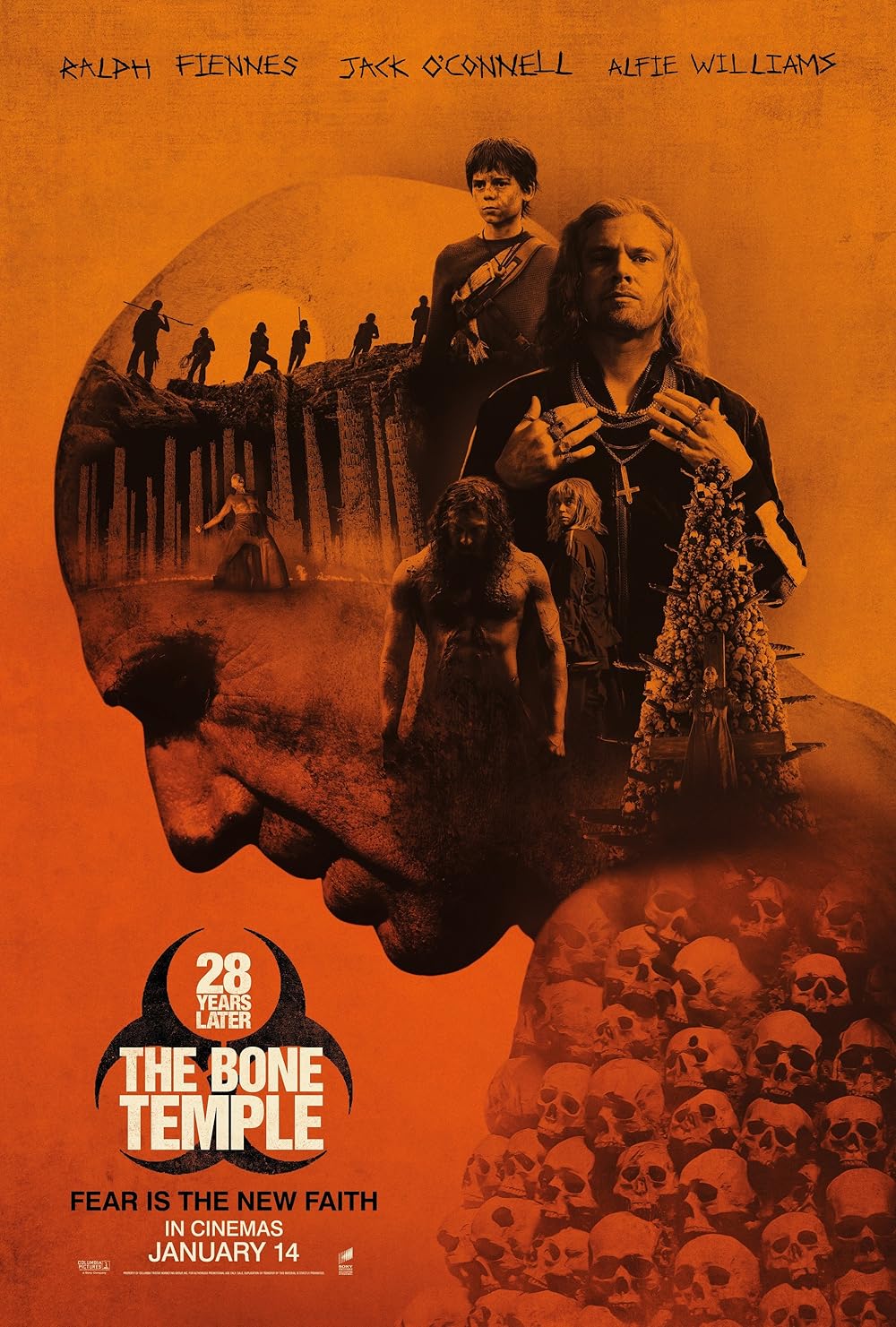

January 16, 2026

|

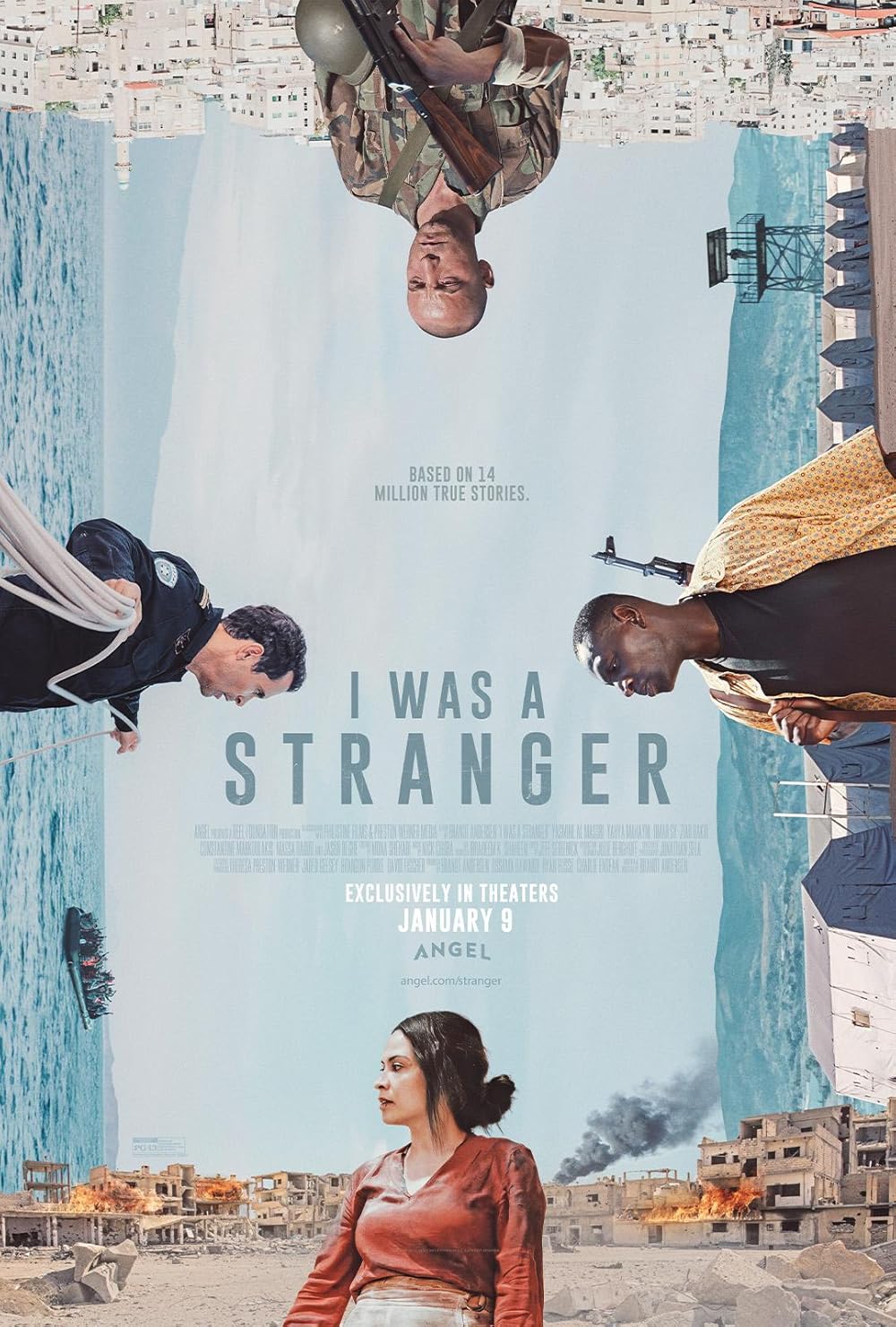

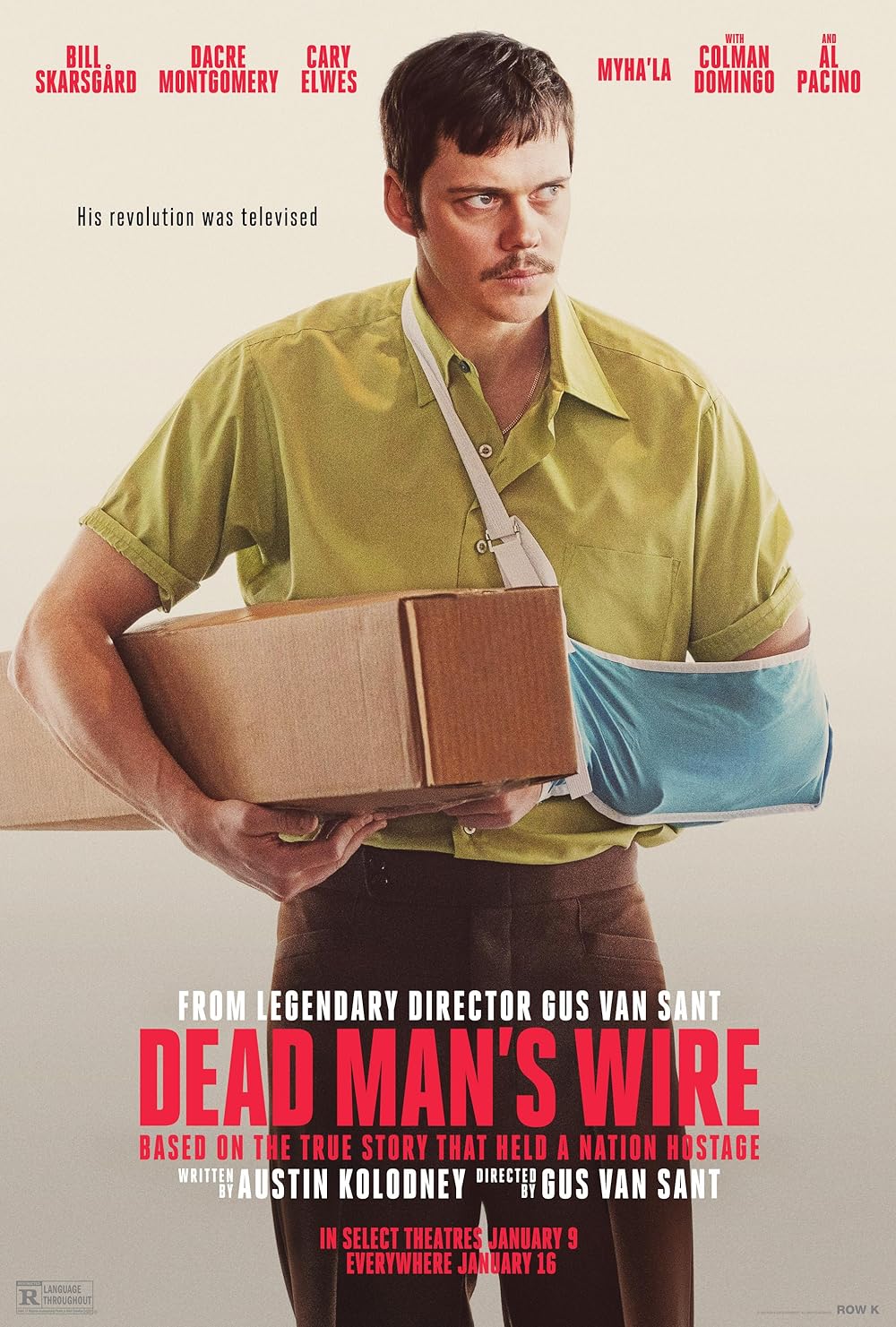

January 9, 2026

|

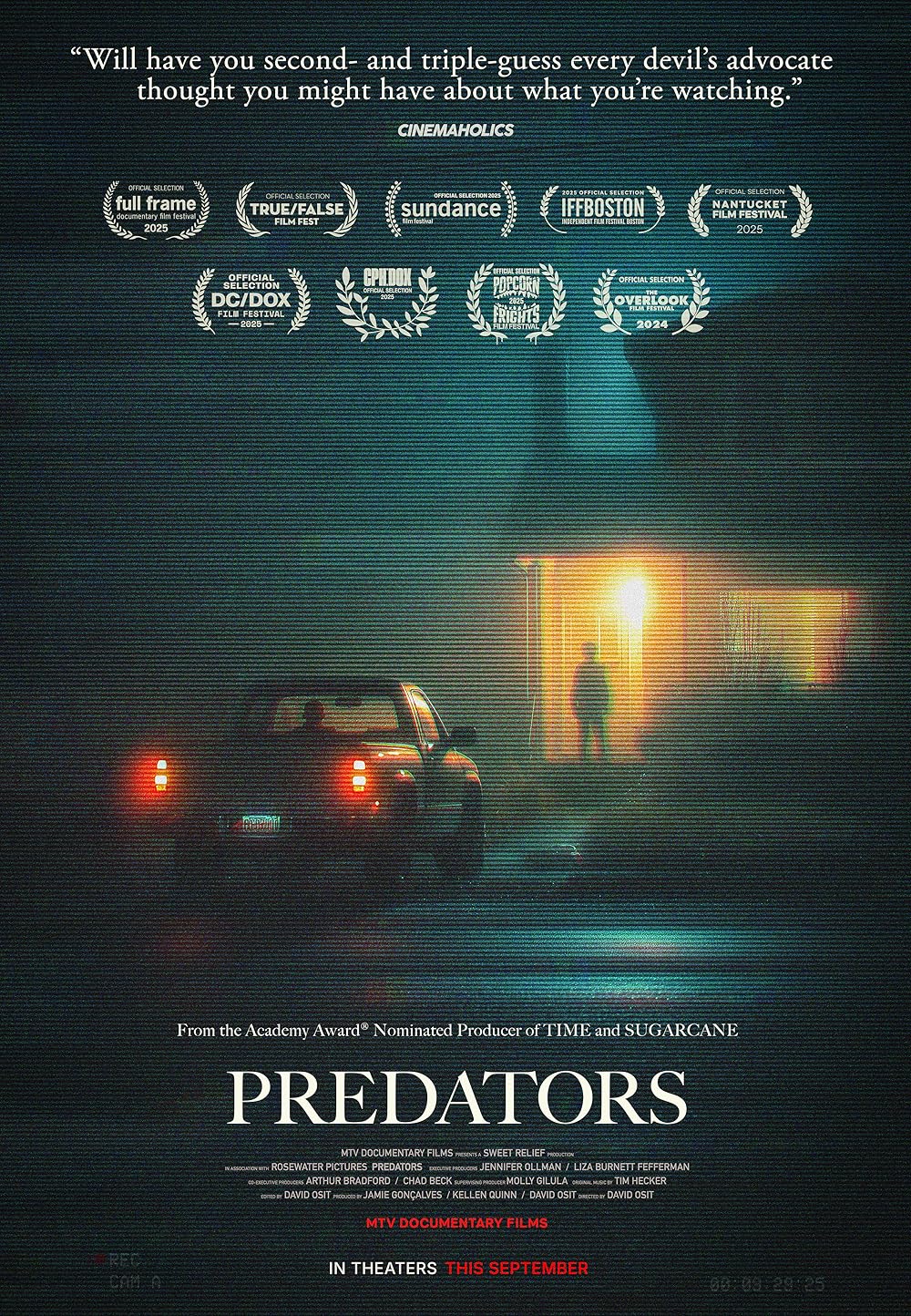

January 2, 2026

|

December 26, 2025

|

December 19, 2025

|

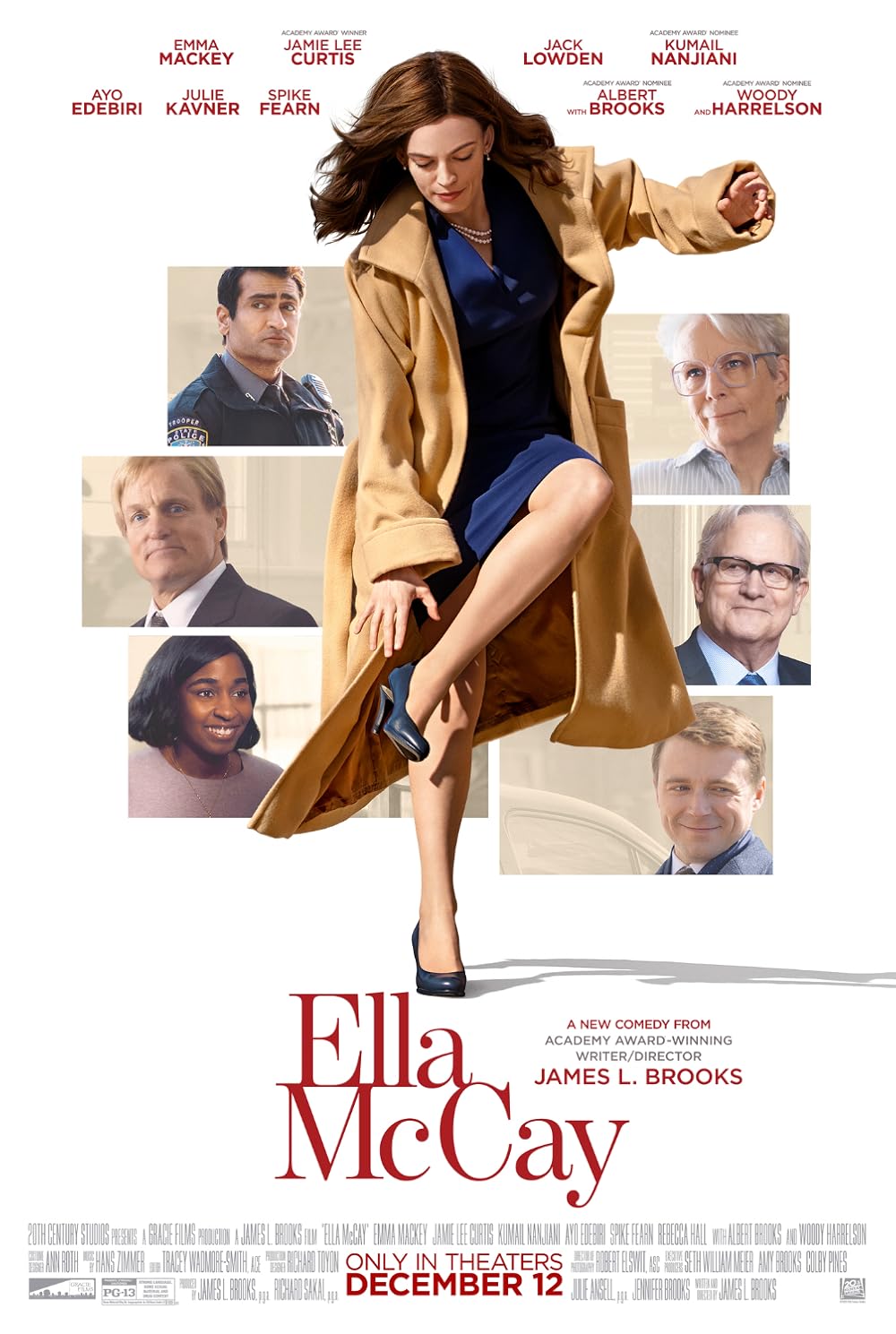

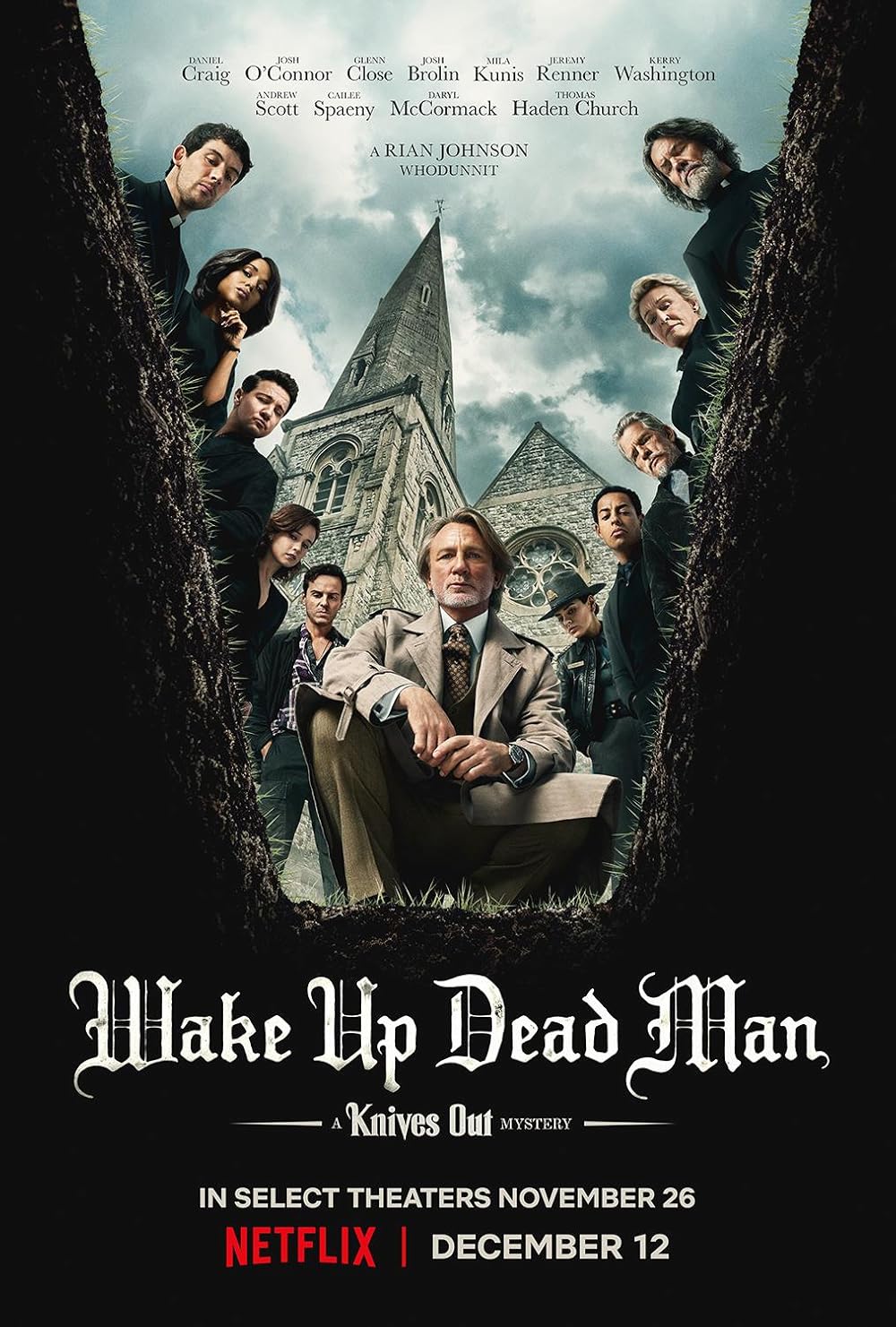

December 12, 2025

|

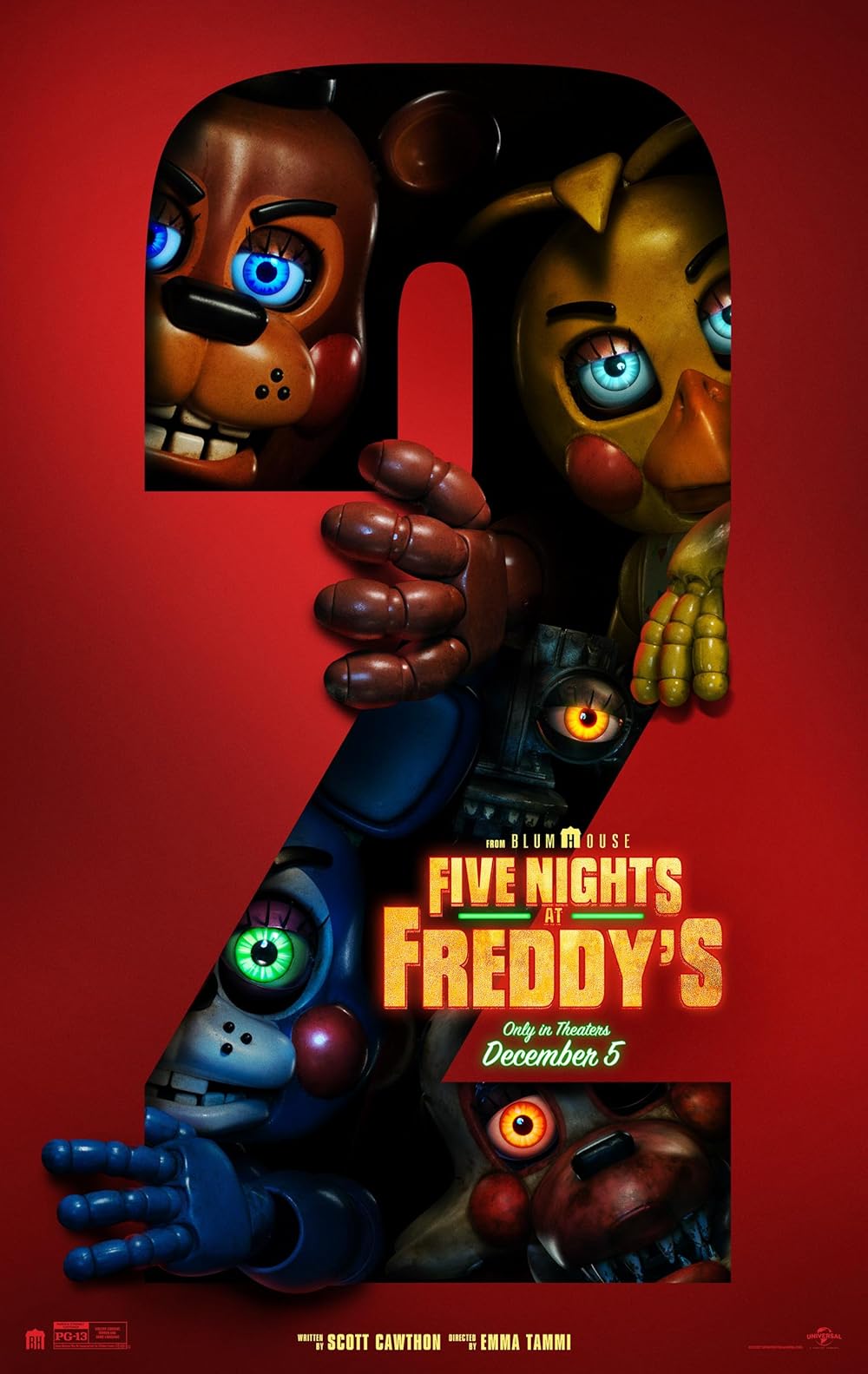

December 5, 2025

|

|

|

|

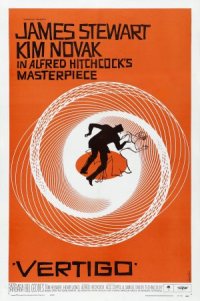

Vertigo

(1958)

Directed by

Alfred Hitchcock

Review by

Zach Saltz

Theodor Reik

tells us that the supreme goal of human love, as of “mystical love,” is

identification with the loved one.

A romantic relationship between two people is defined as a unit,

a single cohesive bond.

The

very act of sexual intercourse involves two bodies forming a harmonious

single figure; any fan of Gothic literature knows that the most enduring

love scene of the genre is between Cathy and Heathcliff, when Cathy

quietly tells herself that she, herself, is Heathcliff.

The

perception becomes difficult when we consider how a woman’s identity is

inherently shaped by the man who controls her.

This is not a two-way street, however; the man, bequeathed in

Apollonian brute and intellect, is the proprietor, not the consumer.

She is his pawn, and in

Vertigo (1958), she lives and breathes not in her identity, Judy,

but in the identity the man she loves wants her to become -- that of

disillusioned and troubled Madeleine, who herself is possessed by the

dead spirit of Carlotta.

Judy becomes Madeleine because Scotty tells her so, and Madeleine

becomes Carlotta because Gavin tells her so.

What is unaccounted for, however, is the paralyzing effect this

has on the viewer; are we watching a psychological thriller, a murder

mystery, or a perverse, voyeuristic tale of sexual fantasies?

What

Vertigo isn’t, simply, is the

story of a man who falls in love with three different women all

contained within the same body; it’s something much more elusive and

abstract, like the dream sequence midway through the film (a hallmark of

Hitchcock seen in some of his other films).

Perhaps the dream provides the necessary evidence to explicate

the meaning of the film; for that sequence provides the barrier in

between a routine detective procedural (man stalks woman hoping to find

catalyst to her insanity) and surrealist painting (man attempts to

reincarnate sentimentalized vision of fractured beauty).

The dream transforms everything -- what is real, what isn’t, and

what we should truly be afraid of.

The central

theme of Alfred Hitchcock’s films is that of identity.

Whether it’s a deadly game of false identities (Notorious),

identities that should have remained secret (The

Man Who Knew Too Much), or complete amnesic submission into the

subconscious (Spellbound),

the Master of Suspense was obsessed with the concept that it is our

identity, and its subsequent loss, that creates the most terrifying and

chilling tales.

That

prospect may be frightening, but what is more disturbing, the

wonderfully gothic

Vertigo

suggests, is trying to dig up that very same identity which we have

lost.

One must

finally ask the question whether the film misogynistic in its

underpinnings.

I do not

think so, for a number of reasons.

First, the central psychological conflict -- that of a fear of

heights, or, vertigo -- renders the traditionally imperious male hero

incompetent and unable to control his sentimental emotions, something

traditionally attached to the diminutive female.

The ploy surrounding Madeleine’s idolatry of Carlotta is later

revealed to be a ploy with the purpose of duping fearful Scottie -- and

it works beautifully, of course.

There are

also many elements laced throughout

Vertigo that can be easily

mistaken for overt sexism.

For instance, the film is told almost completely from Scottie’s

perspective, and the one scene presented from Judy/Madeleine’s viewpoint

-- the revelation concerning the murder -- is quickly torn up into

pieces.

Hitchcock is not

suggesting that the woman’s perspective is unimportant; it’s almost the

complete opposite.

In this

scene, we are shown the raw reality, unencumbered by male sexual drives

of grandeur and fantasy.

The woman wants the truth, however much it may hurt, and she knows that

the man will not be able to accept it.

By tearing up the past, she is protecting herself against the

anger and manipulation of the man who only thinks he knows what he’s

dealing with.

The film’s

palette may suggest another facet beneath the façade of convention.

Hitchcock uses vibrant reds to exclamate traditional sensuality

expressed in the color; when we first glimpse the rapturous figure of

Judy/Madeleine, her surroundings are drenched in red, pulsating blood

from the veins into the heart.

The opening images, undoubtedly influenced by the electric pop

art modes of the emerging French New Wave, focus on the jigsaw-like

puzzle of a woman’s visage, perpetuating radiant sensuality and shades

of green and grey, however, are Hitchcock’s reality; for even in the

transcendent first image of Judy/Madeleine, she is wearing a green

dress, and in the unforgettable shot of Judy/Madeleine in the grey suit,

beneath the green fog.

Perhaps the

final curiosity of

Vertigo is

the character of Midge.

Her

purpose in the film is unclear; she is not Scottie’s secretary or love

interest or really any sort of vital character rendering a major effect

on the outcome of the story.

The only way we can assess her is by labeling her Scottie’s “best

buddy”, an archetype confined nearly inseparably to someone of the same

gender as the hero.

Midge,

though quietly sexy, is polymorphously androgenic, appropriately labeled

“boyish yet motherly” by Karen Hollinger.

Her playful banter with Scotty suggests a sexually ambiguous

persona, but it isn’t until she paints her head on the body of Carlotta

(in a scene Dali would appreciate) that we learn of her longing for

Scotty.

But she will never

be recognized because her sexuality is too quiet, to say the least.

The only red she wears are in the rims of her eyeglasses.

But is this all she serves?

Or does Midge really hold the keys to something more integral to

the story than we may think, on the surface?

Rating:

# 63

on Top 100

|

|

New

Reviews |

Reactions to the Nominations

Written Article - Todd |

2026 Oscar Predictions: Final

Written Article - Todd |

Todd Most Anticipated #5

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

10th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Zach |

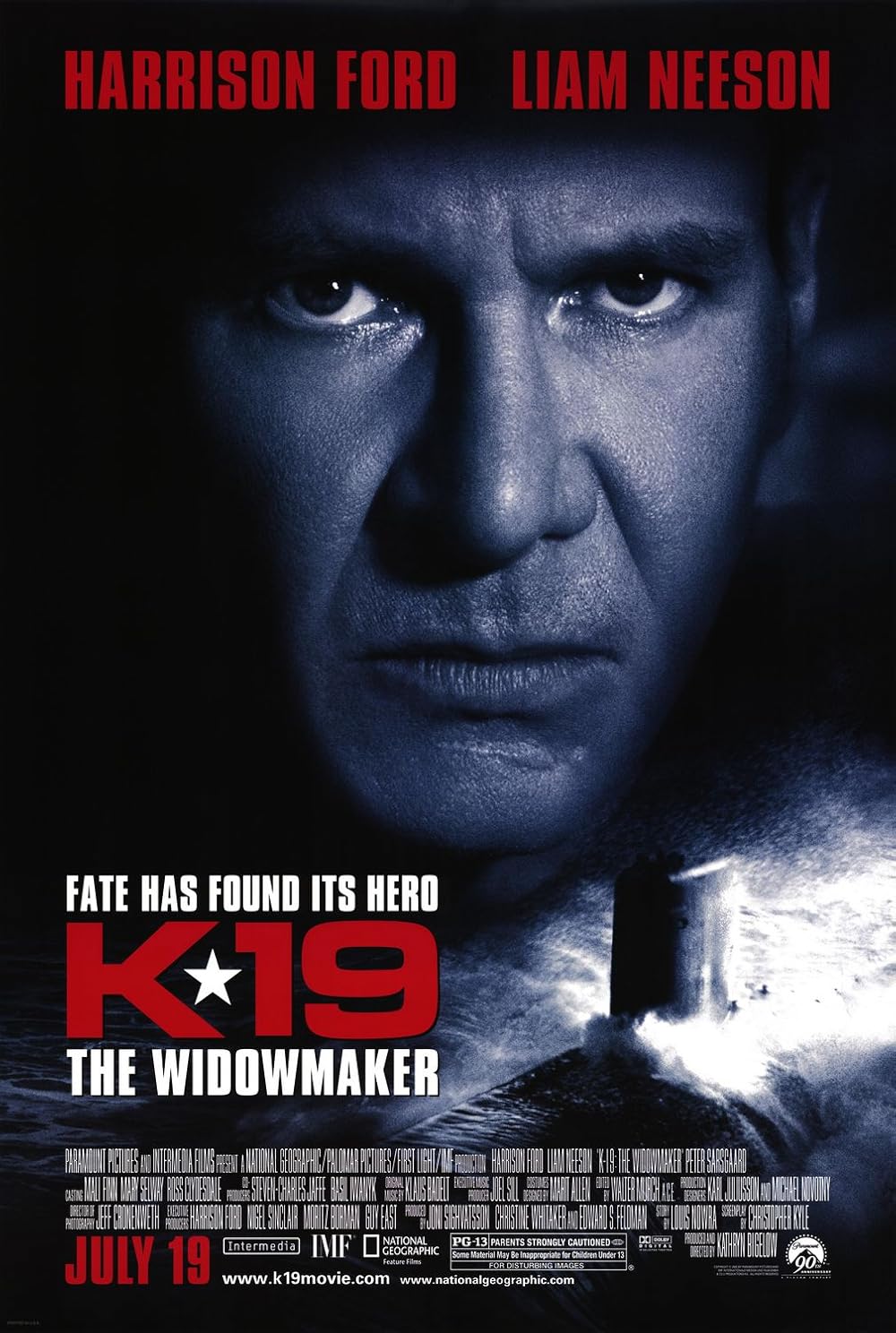

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

2027 Oscar Predictions: Jan.

Written Article - Todd |

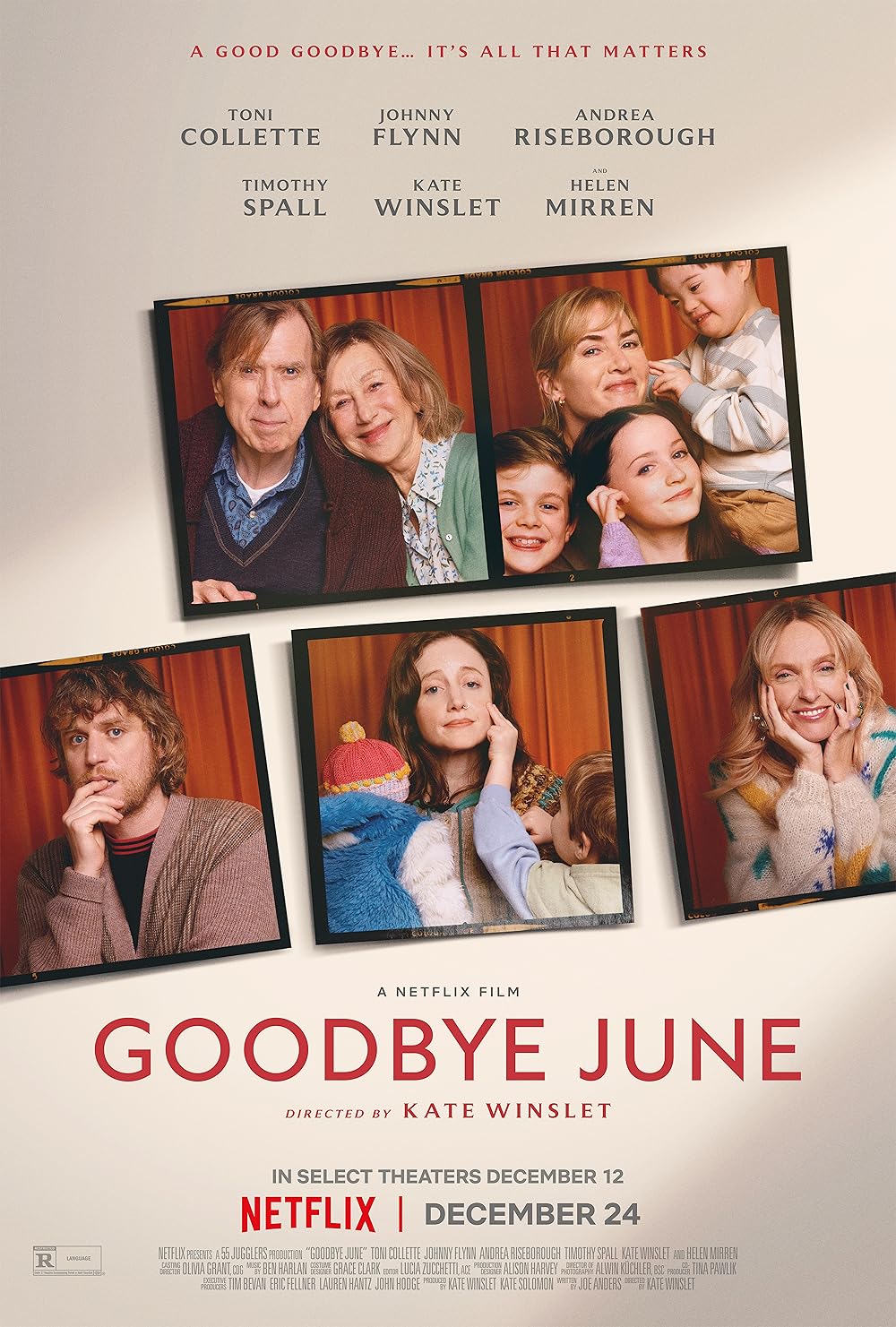

Terry Most Anticipated #2

Podcast Featured Review |

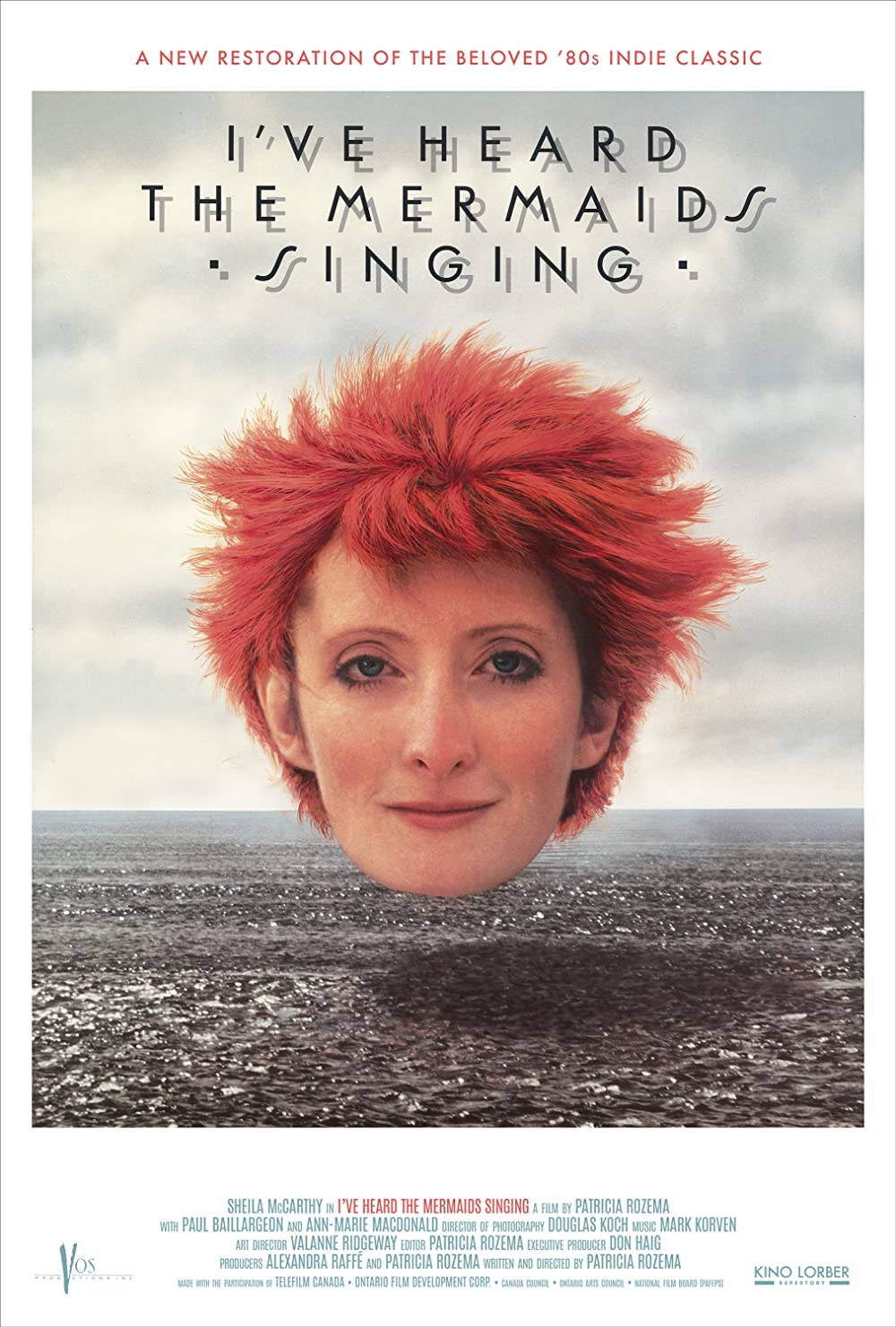

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

20th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Trivia Review - Adam |

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Terry |

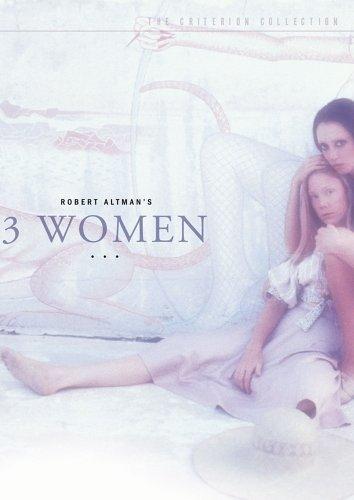

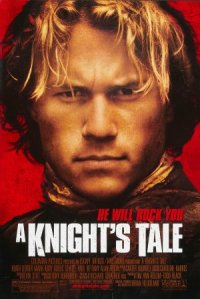

25th Anniversary

PODCAST DEEP DIVE |

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Terry |

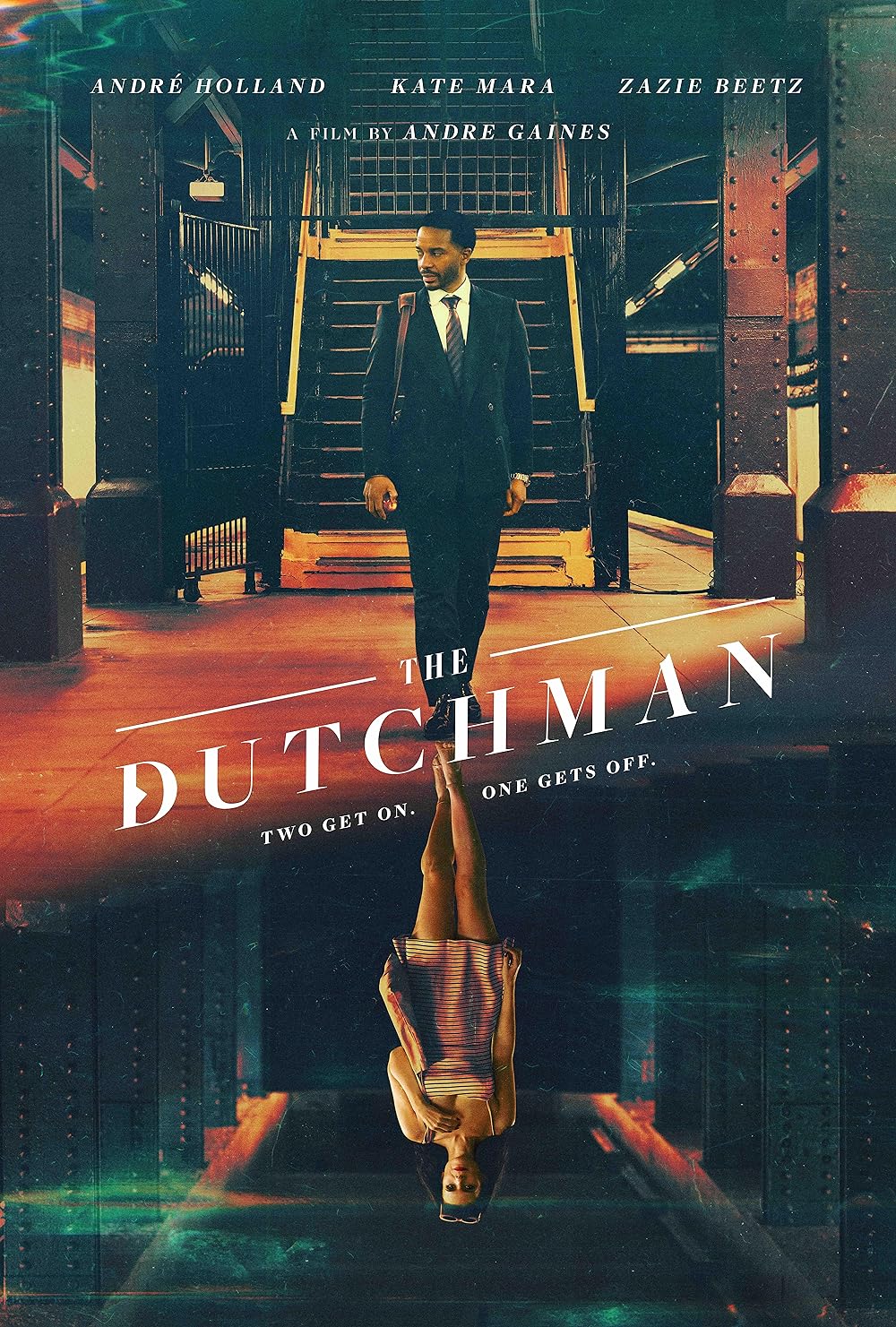

Indie Screener Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

|

|

|