|

New

Releases |

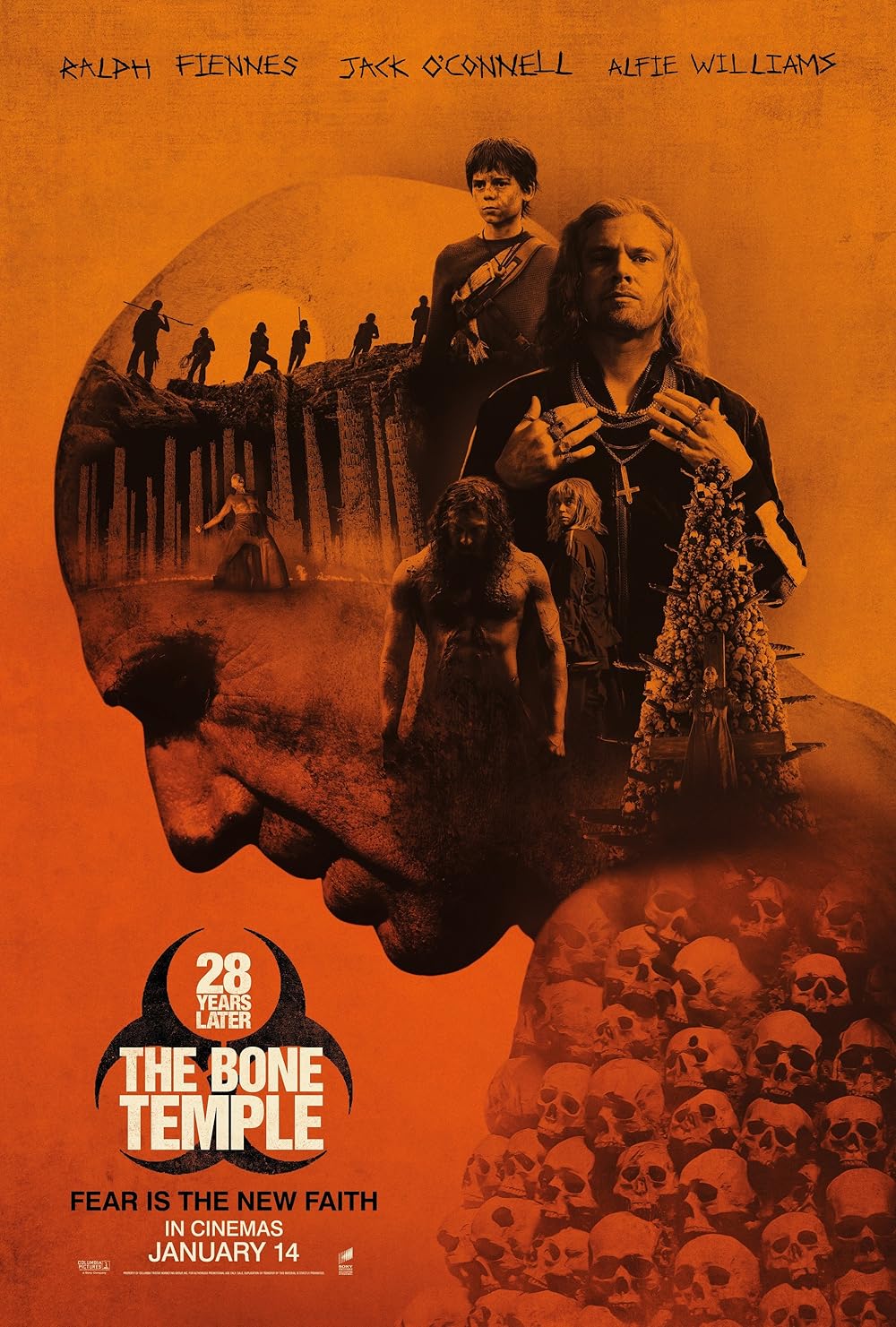

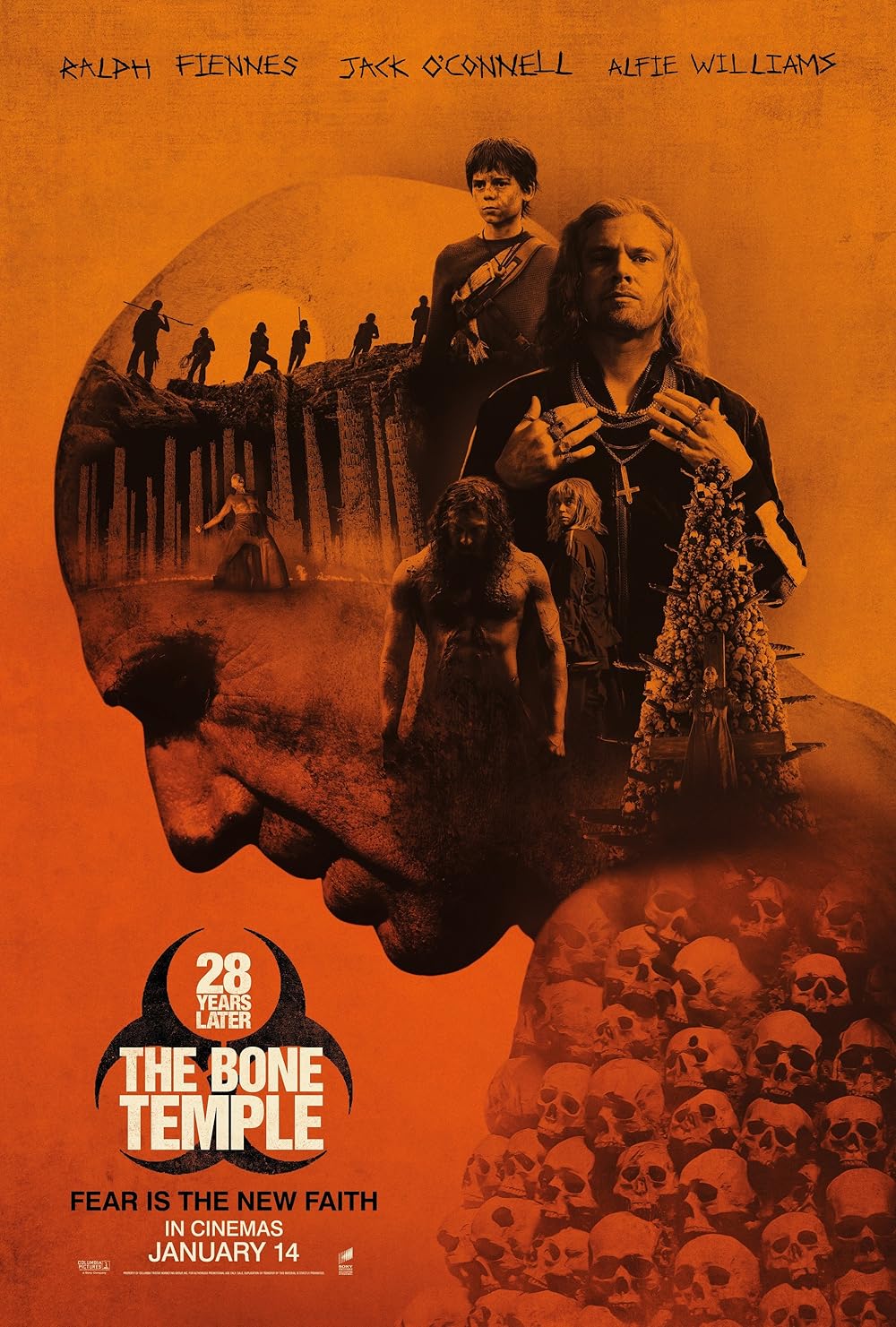

January 16, 2026

|

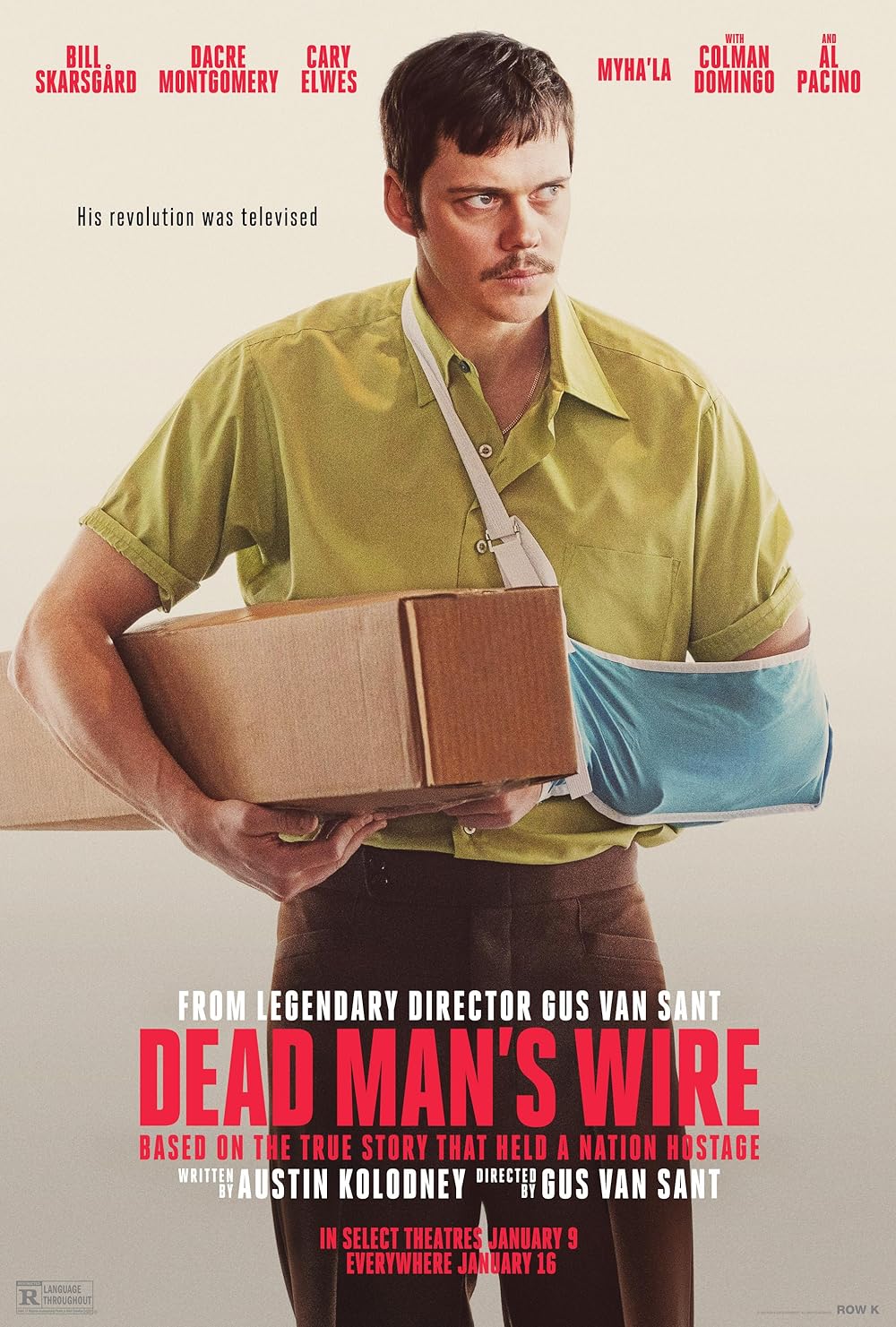

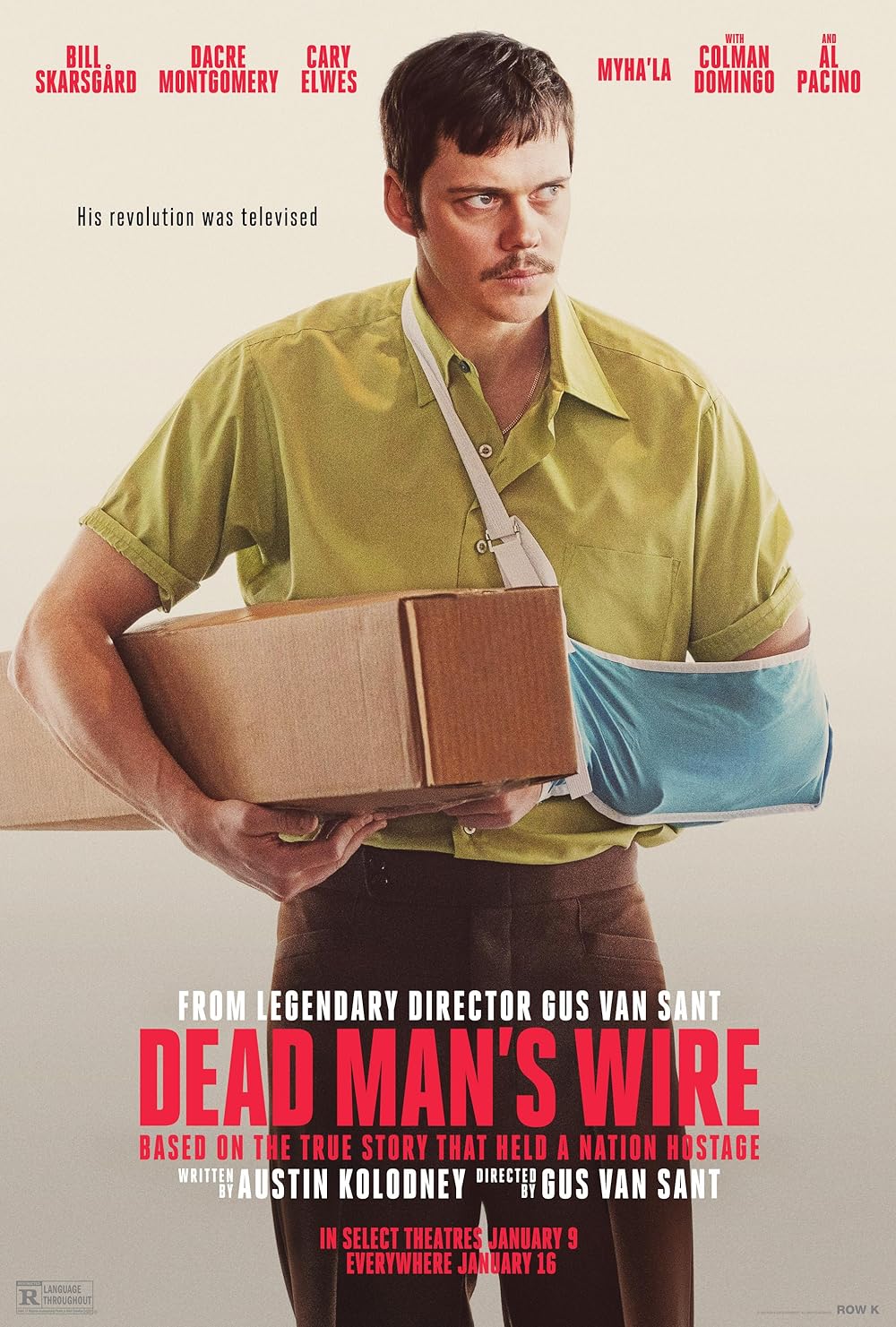

January 9, 2026

|

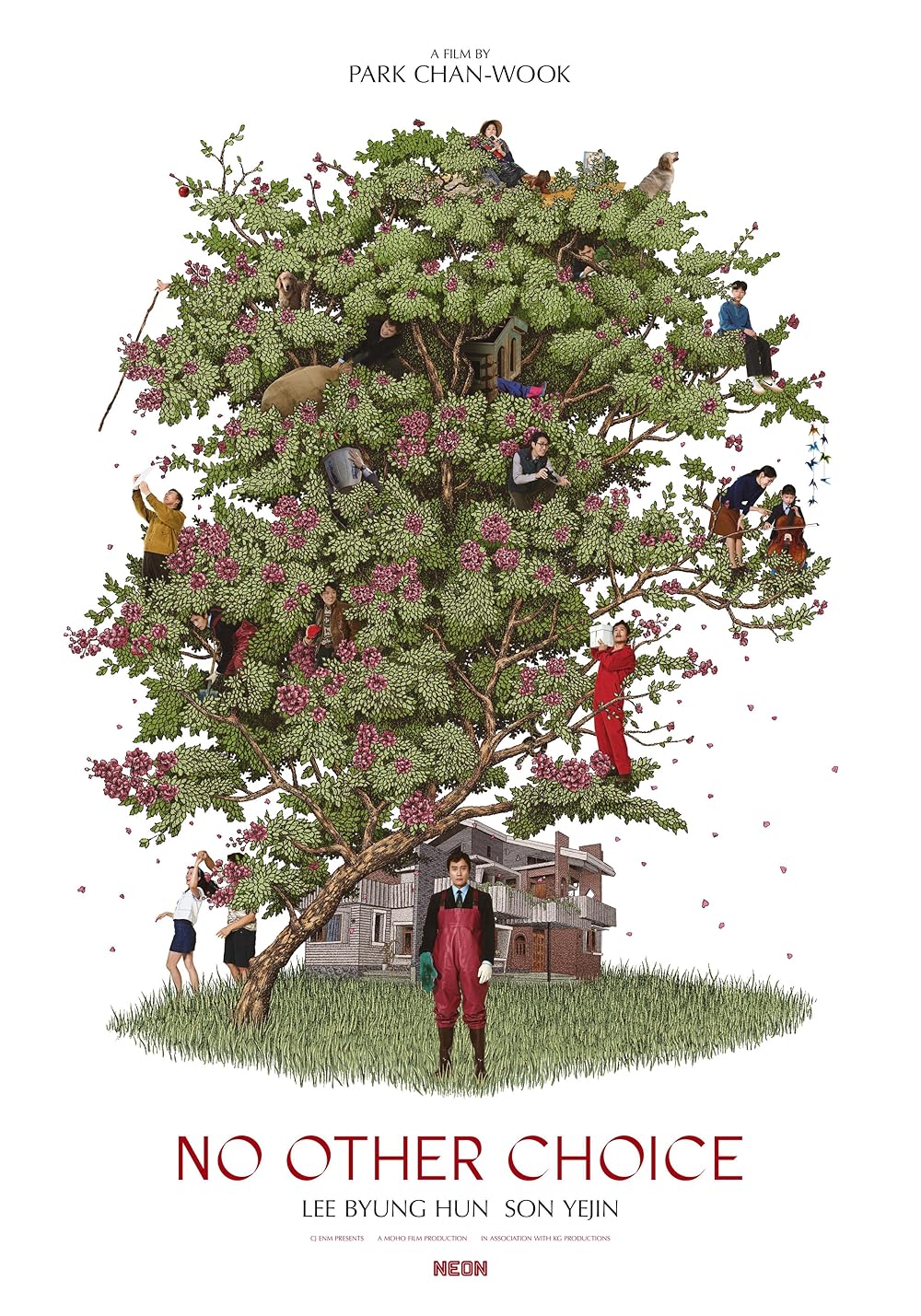

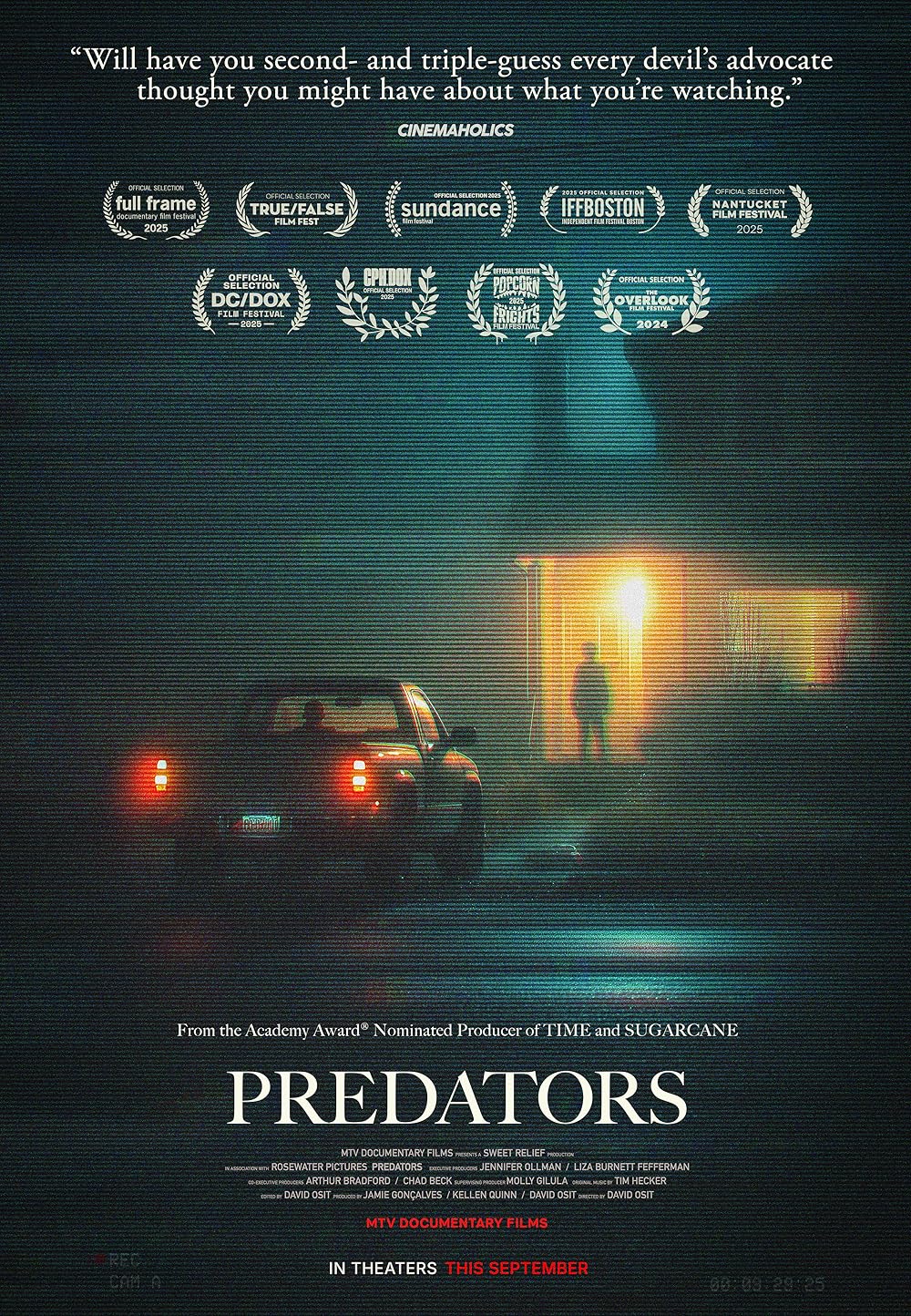

January 2, 2026

|

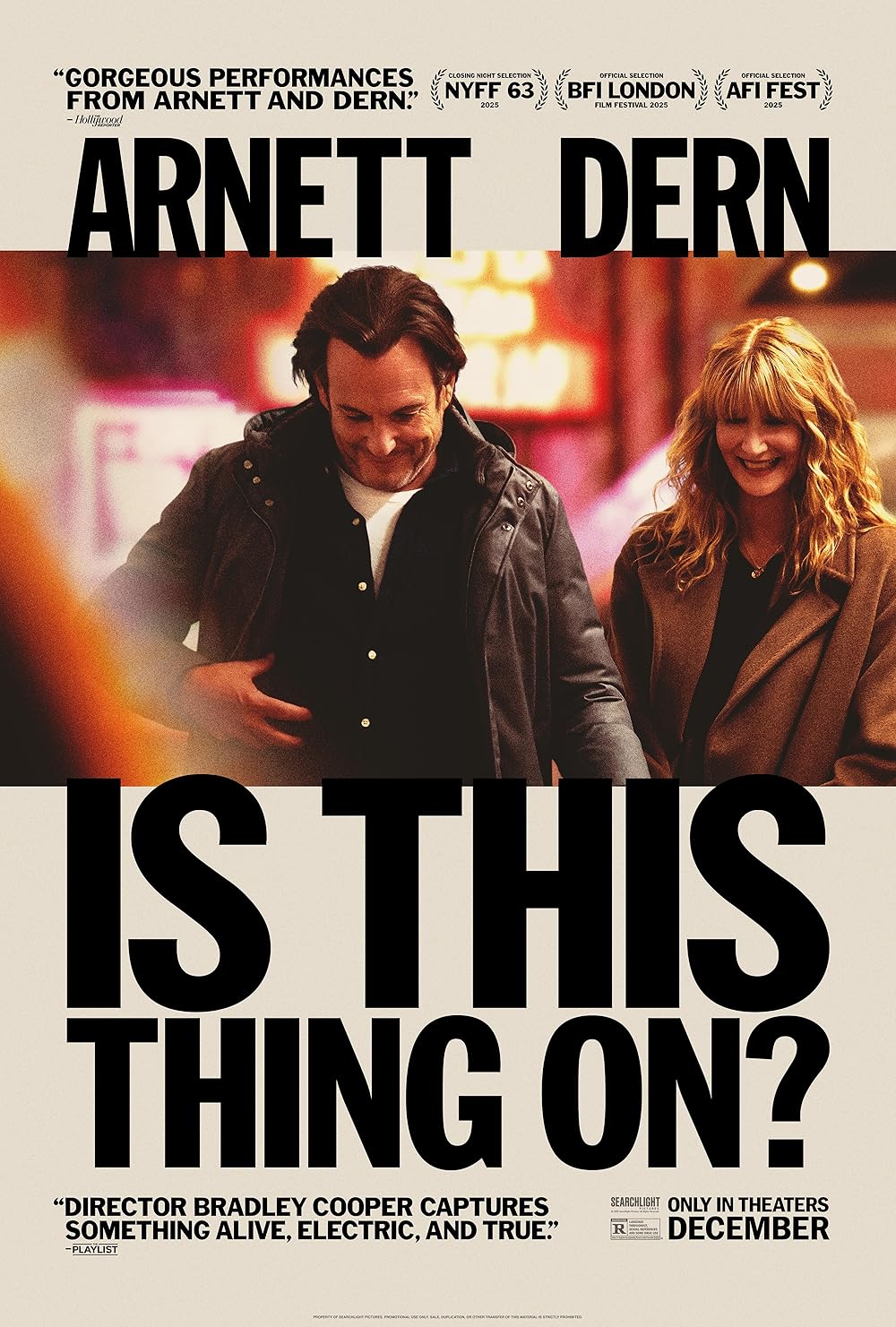

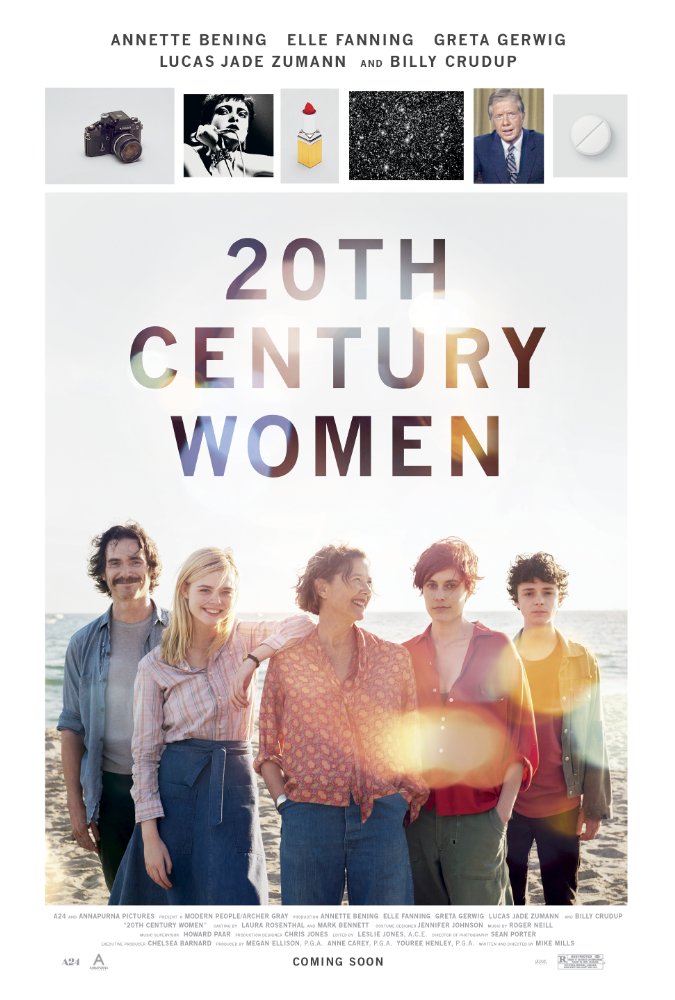

December 26, 2025

|

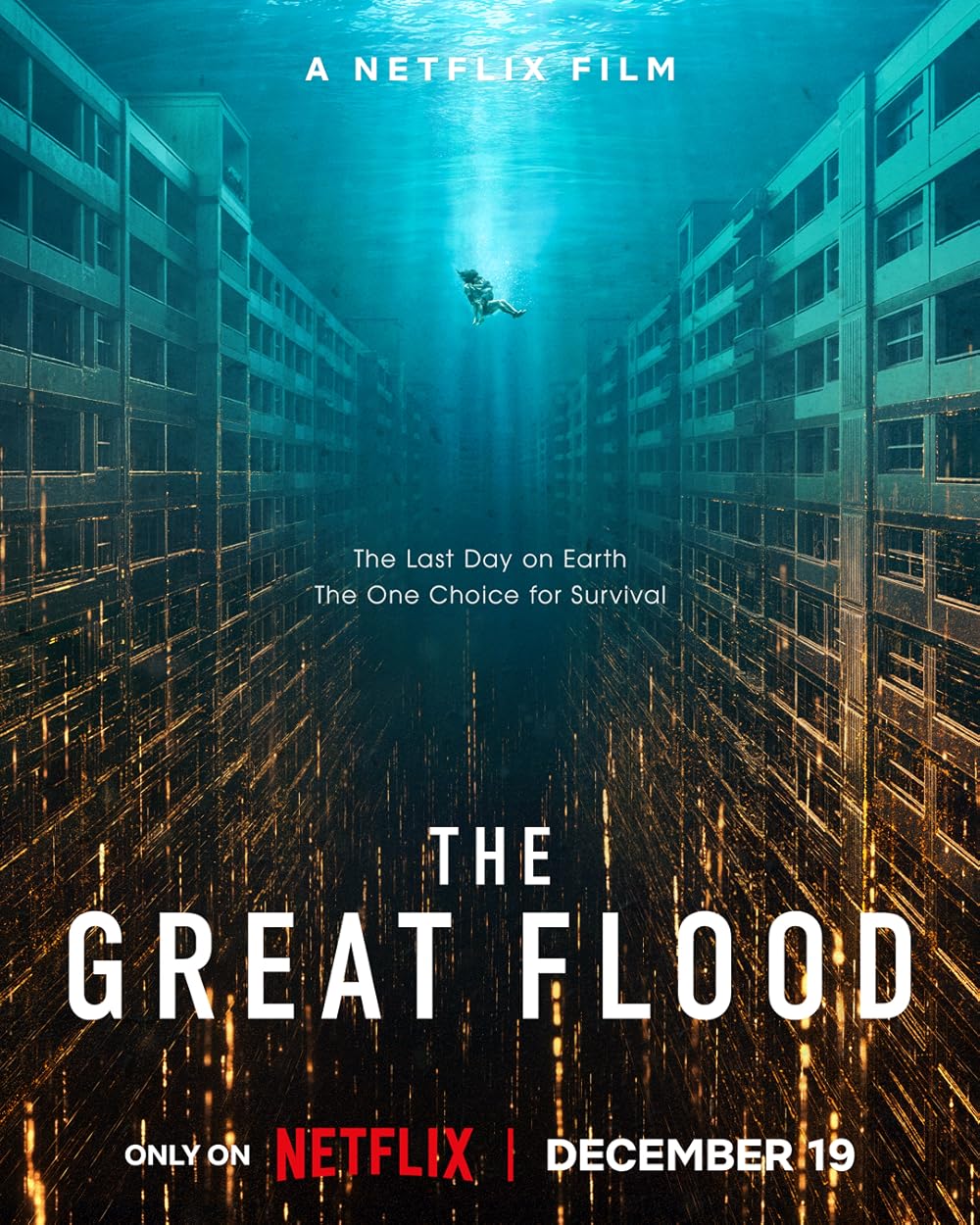

December 19, 2025

|

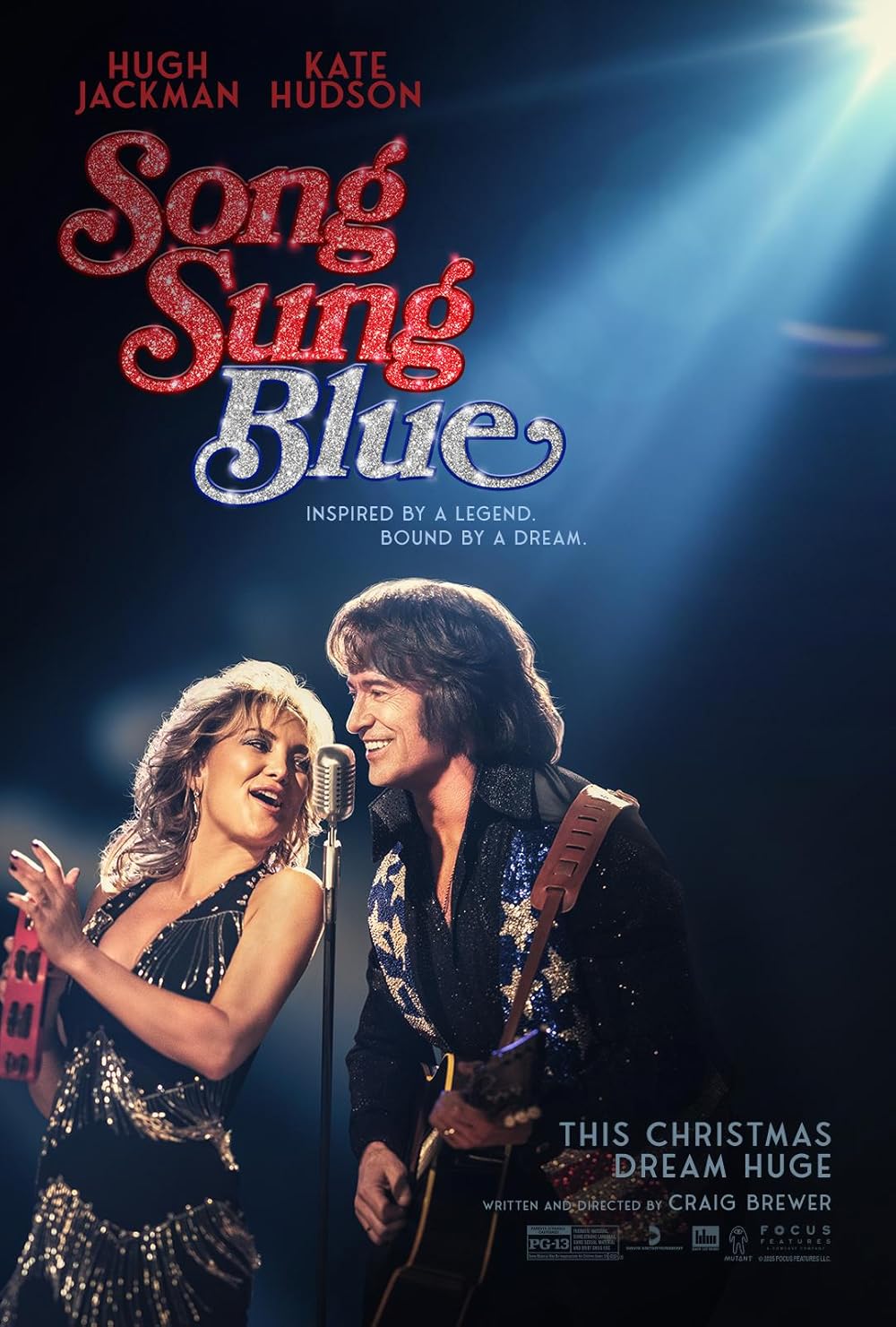

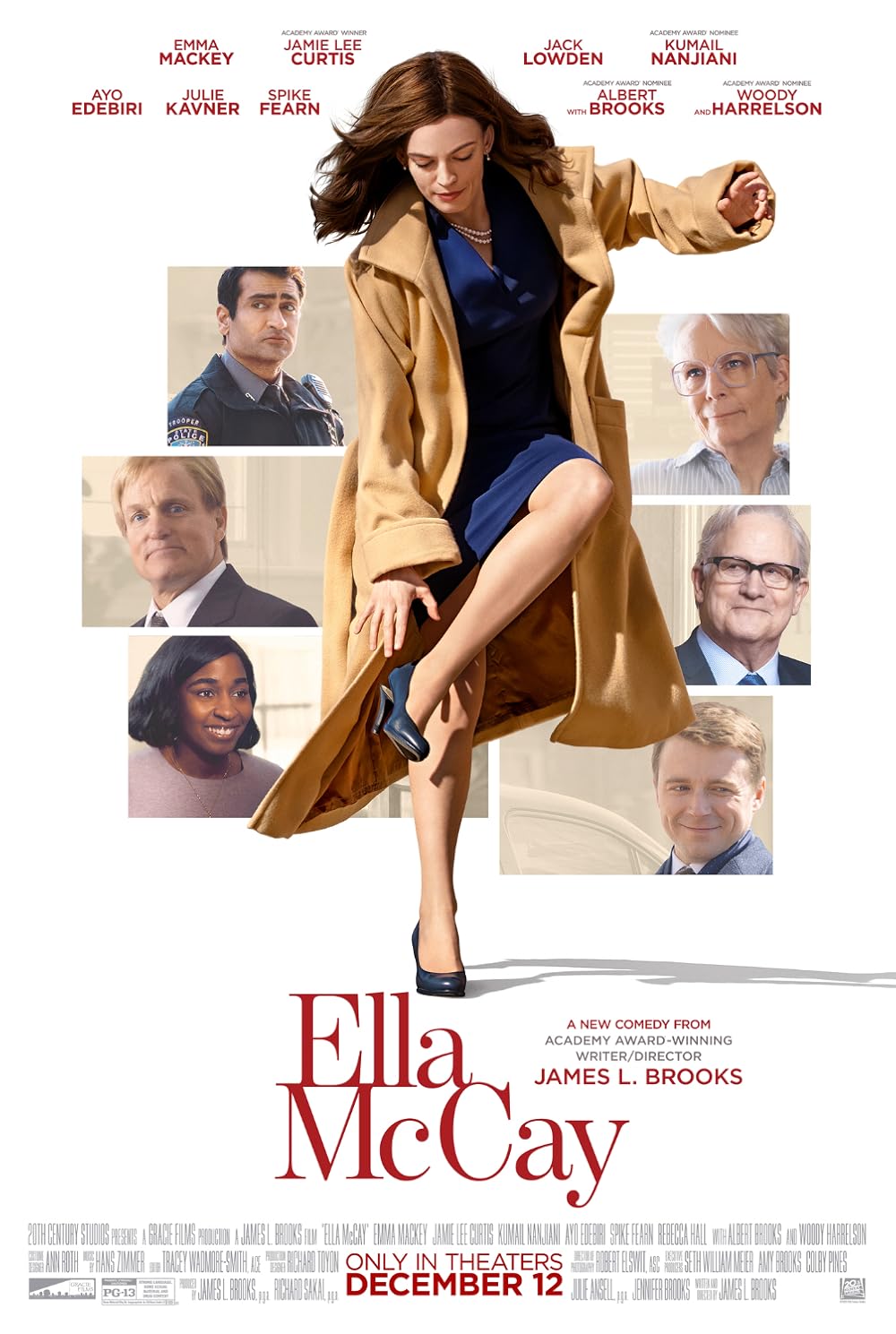

December 12, 2025

|

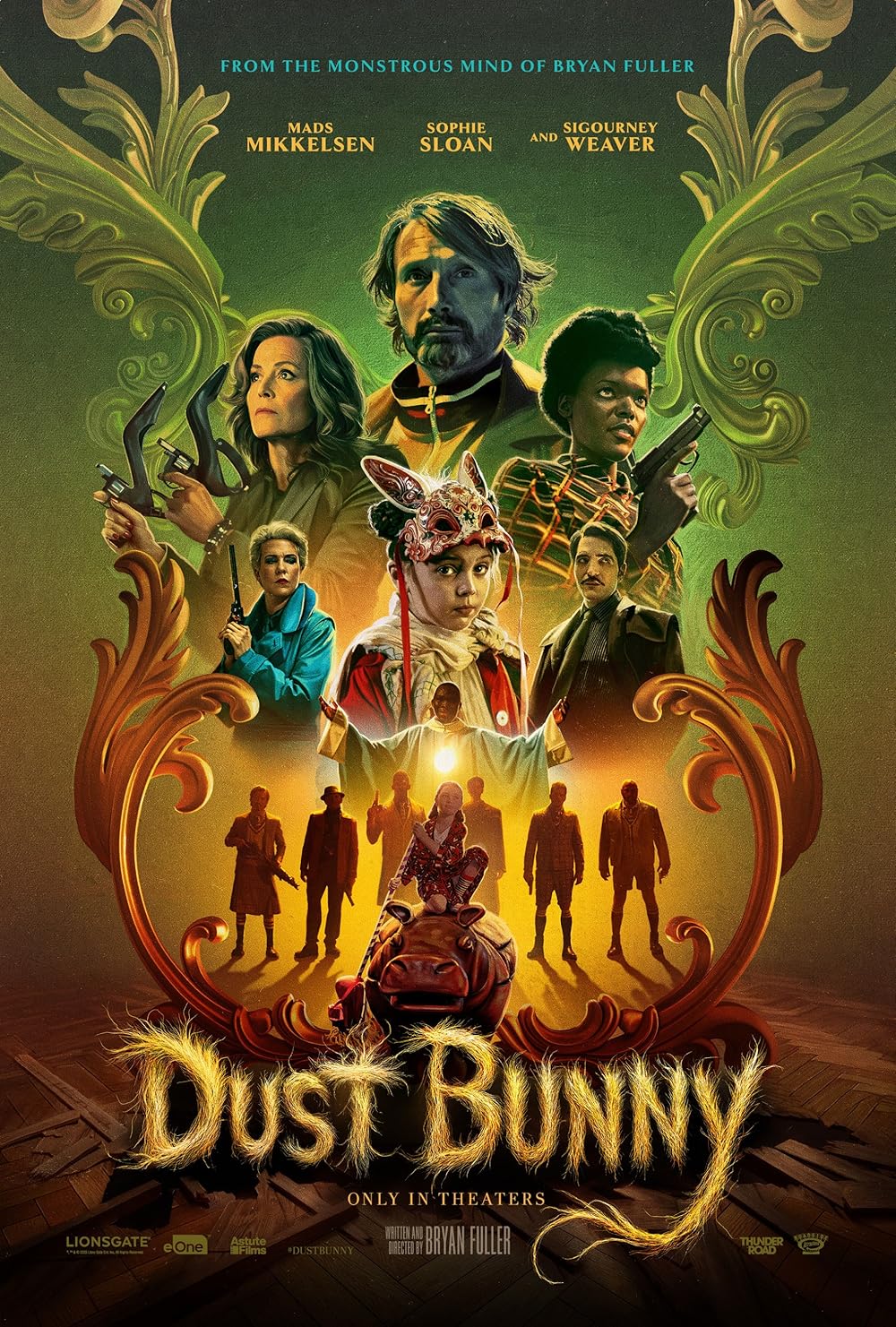

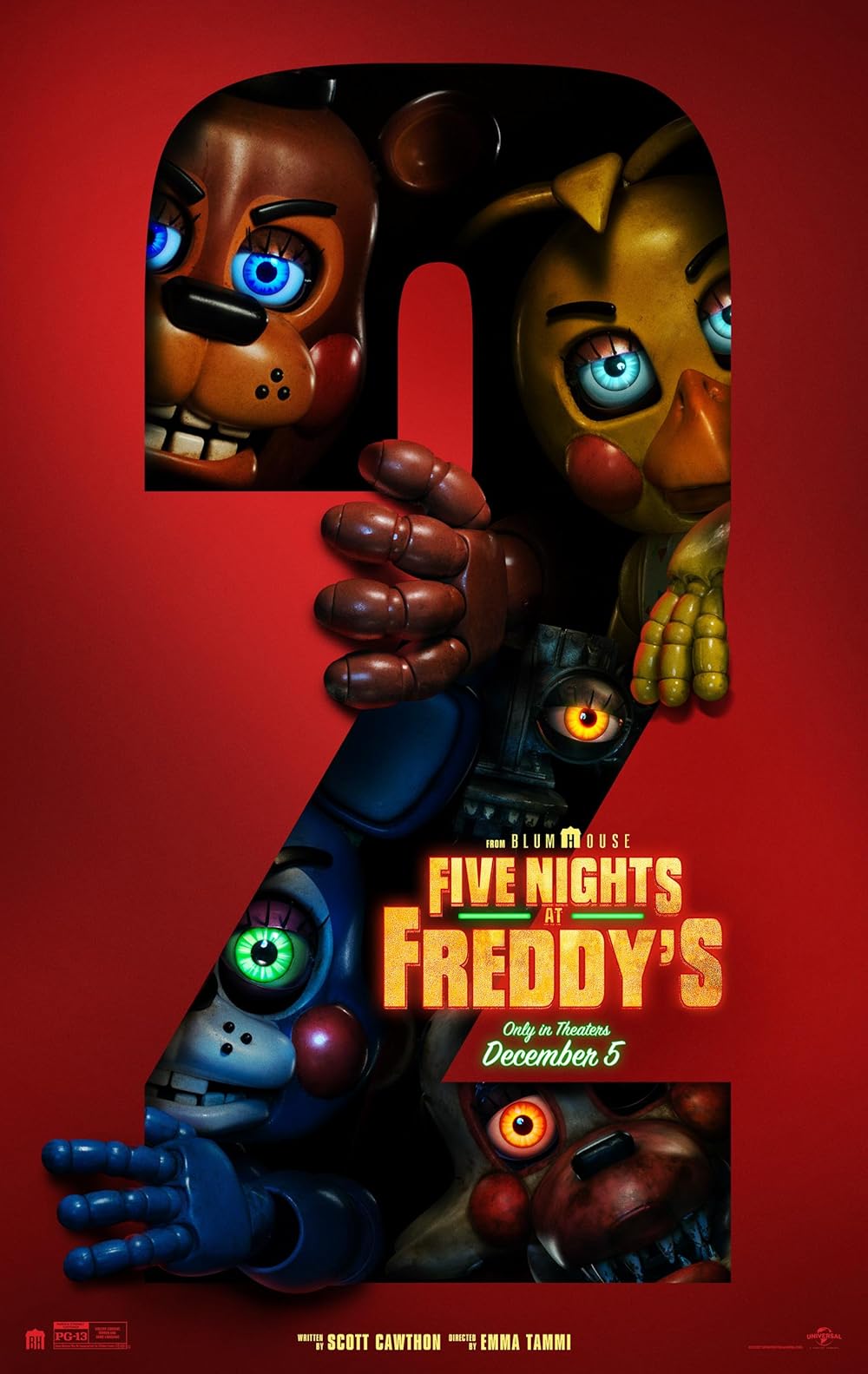

December 5, 2025

|

|

|

|

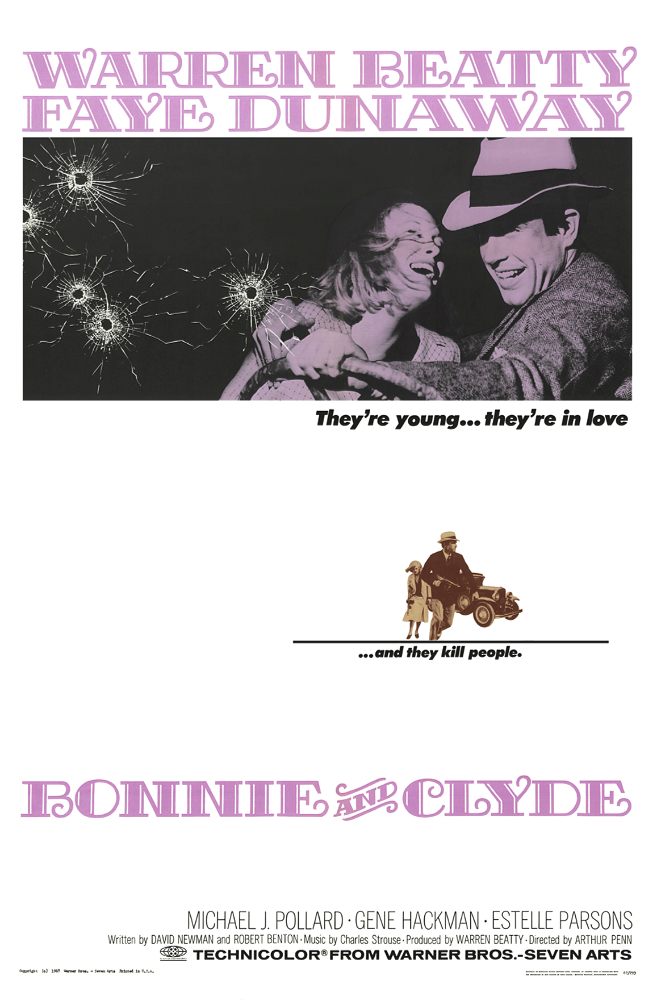

Bonnie and Clyde

(1967)

Directed by

Arthur Penn

Review by

Zach Saltz

“Some day, they’ll down together

They’ll bury them side by side,

To a few, it’ll be grief,

To the law, a relief,

But it’s death for Bonnie and

Clyde.”

Arthur

Penn’s

Bonnie and Clyde

(1967) belongs on that short list of uniquely, unequivocally American

masterpieces that include

A

Streetcar Named Desire (1951),

In Cold Blood (1967), and

Fargo (1996).

The key

word in that distinction is American; the films aforementioned

all contain elements -- overt and abstract -- that could only be

mastered and materialized by writers and filmmakers that know the

landscape of

America

intimately.

Bonnie and Clyde

does indeed know America better than any scholar or history book will

tell you.

It knows that

famous Americans thrust into the national spotlight -- like the film’s

protagonists, Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker -- are usually painfully

normal people, with tendencies, flaws, and urges just like you and me.

It knows about America’s

insatiable yearning for the spectacle, for fame, and for wealth and

material goods.

It also

knows a bit about loneliness, too; the film is set during the Great

Depression in the area of what is now collectively known as “The Dust

Bowl.”

All the characters

of the movie are isolated in some way or another, and feel an

overwhelming emotion of liberation doing the only thing they believe

they were sent on Earth to do:

To rob banks, naturally.

The story is

very simple.

The opening

scenes show a bored Bonnie Parker, basking cheerfully naked around the

room, with the galore and sensuality of a starved sex kitten.

Clyde Barrow waits carefree outside her window, next to her

mother’s car, apparently ready to steal it.

Their eyes meet.

He

tells her that he robs banks.

She doesn’t believe him.

He drives over to a bank and sticks up the teller -- only to be

told that the bank is now out of business and holds no tenure (Clyde

of course forces him to tell Bonnie this so she knows he isn’t lying).

Bonnie and

Clyde continue to rob banks, but it’s very difficult to deem them

cold-blooded thieves.

They’re simply too nice, naïve, and desperate for anyone to think lowly

of them.

Along the way,

they pick of a dumb car hand named C.W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard) and

eventually meet up with Clyde’s older brother, Buck, and his wife,

Blanche (Gene Hackman and Estelle Parsons).

In a sense, they’re all as innocent as Huck and Jim floating down

the

Ohio;

but the film is very keen in the way it presents a shifting morality in

regard to social issues of the time.

Huck and Jim were defying a racist system of caste and hatred;

Bonnie and Clyde are defying a system that flatly turns its back on

people in a time of national economic crisis.

This is shown no more true than in the early scene were Bonnie

and Clyde meet up with an old farmer visiting his repossessed house, and

promptly give him a pistol to shoot at the repossession sign.

There is

another scene later when Clyde is robbing a bank and asks a bystander if

the money he is holding is his own or the banks.

The bystander tells him it is his own, and

Clyde tells him that he can keep it.

It would be easy, then, to label them as Robin Hoods protecting

average citizens from the scum government, but that would not

necessarily be true either; they are enigmas, these people, at one point

loveable, the next detestable.

Perhaps this quality shows the ever changing American aspiration

to hail someone we love to hate.

Technically,

the film is exemplary in its use of mise-en-scéne to heighten elements

of story and character.

The

exterior tones throughout the film are very bland, suggesting not only

the presence of 1930s dust storms, but a morose, death-like quality that

unabashedly shows the isolation of the protagonists alongside the

foreshadowing of their eventual demise. The use of still photographs,

especially during the opening credit sequence, establishes a nostalgic

mood -- a time and place that was long, long ago, but whose lessons and

morals can still be felt in America

today.

There are

three scenes in particular that simply left me awestruck in their

technical majesty and enhancement of emotion through mise-en-scéne.

These scenes also provide integral clues as to Bonnie and

Clyde’s unalterably tragic fate. The first is a high angle

shot of Bonnie running across a corn field, with Clyde chasing her down.

What is particularly amazing about this view is the slow movement

of an unseen cloud overhead, shadowing over the entire wheat field,

including Bonnie and Clyde.

This shot would be easy to create nowadays, with the innovation

of computer generated effects; but one can only believe that this shot,

filmed nearly forty years ago, was a product of pure and unadulterated

luck.

The cloud present the

first sign of Bonnie and

Clyde’s

downfall, and the wide angle expresses the open freedom of the two

protagonists to do whatever they want -- but are ultimately held at bay

by the cloud, about to beset grief and tragedy upon them.

The second

scene is more of a sequence than a single shot; it is the reunion of

Bonnie and her mother, whom she has not seen in months.

This scene is easily distinguishable from all other scenes in the

film because of the soft focus mid-range shots.

It appears as though there is a party going on, but you could

never tell that because of the dark, foreboding atmosphere in which

director Penn chose to film the scene.

For a while, I suspected that the entire sequence may have been a

dream (furthering this belief was the improbability of Bonnie being able

to reunite with her entire family without the police knowing about it).

But whether it is reality or not is almost beside the point; this

is a completely different and discrete atmosphere from the wild and

vibrant mood when Bonnie and

Clyde

are robbing banks.

It

suggests a very harsh reality, and shows the ramifications that

shameless escapism and a life of crime can have on a normal,

full-blooded family unit, and when Bonnie’s mother says goodbye to her

daughter, we know it is the last exchange that will ever take place

between these two women who, at one point it seems, loved and cared for

each other very much.

The third

scene comes toward the end of the film, and consists of a singe shot.

Both Bonnie and Clyde are at the height of their national popularity, but

find themselves in deep trouble after being shot by the police.

C.W. drives them to an extended family of Okies (perhaps a mirror

reflection of Bonnie’s reunion scene) and asks them to spare some water,

as to heal the wounds.

The

family is dumbstruck; perhaps they have seen Bonnie and Clyde’s names in the paper, perhaps it is just the mere

sight of two bloodied and helpless bodies lying in the back seat of a

car.

Whatever the reason,

the group is stunned, and in the midst of one of the most painstakingly

quiet sequences ever filmed, we see a man in a hat, standing outside

Clyde’s window, quietly caress his bloody hand.

Again, this is beautifully ambiguous; is the man responsive to

the fact that Clyde is by now a

celebrity?

Is he astonished

by the sudden presence of outsiders on his small ramshackle of land, and

in this caress showing his longing for escape from the problems of

poverty and sickness?

Or is

it simply a gesture of human sympathy -- reaching out to help a dying

man in time of crisis?

It’s hard to

believe that, for a while in the mid-sixties, the front-runners to

direct this film were Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Goddard.

It is the unique American perspective and meditation on violence,

notoriety, and stark isolationism contrasted with rugged individualism.

I do not mean to be course or narrow-minded, but could anyone

outside this country convey the longing and inexplicable sadness

expressed in this motion picture?

The speech and dialect of the film may be prescribed as banal,

but there is a certain poetic beauty in those final few haunting lines

of the poem Bonnie sends in to the papers to be published.

Her and Clyde know that their fates are up to the heavens, but

for one brief, gleaming moment they see a path that may lead out of

their abhorred and dull lives, and that route was through each other --

all of this implied in their last gaze into each other’s eyes moments

before their sudden and violent deaths.

This makes

Bonnie and

Clyde a stunning American statement on the desire to love and to be

loved, even if you are detested by everyone else.

Rating:

# 39 on Top 100

# 1 of 1967

|

|

New

Reviews |

Reactions to the Nominations

Written Article - Todd |

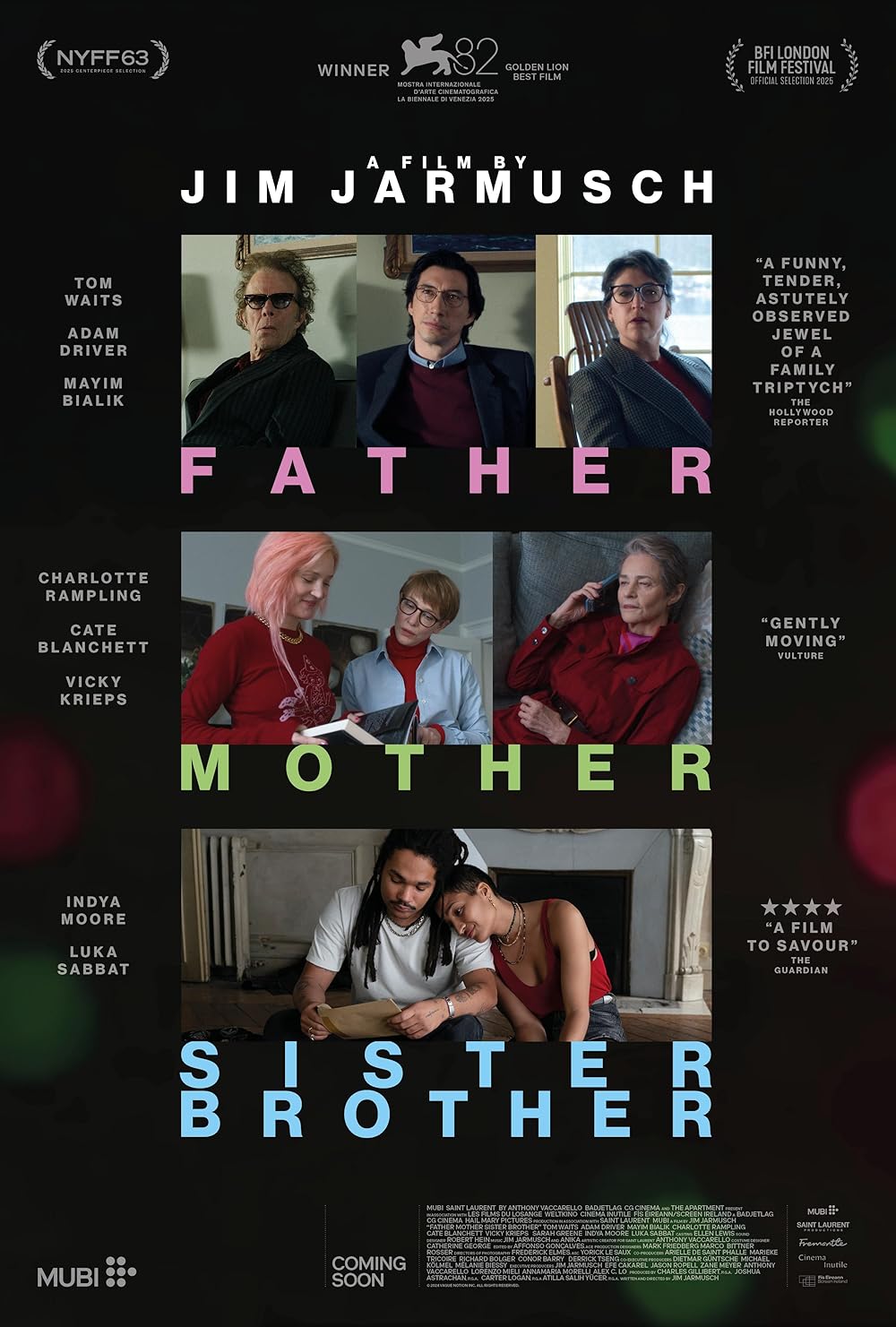

2026 Oscar Predictions: Final

Written Article - Todd |

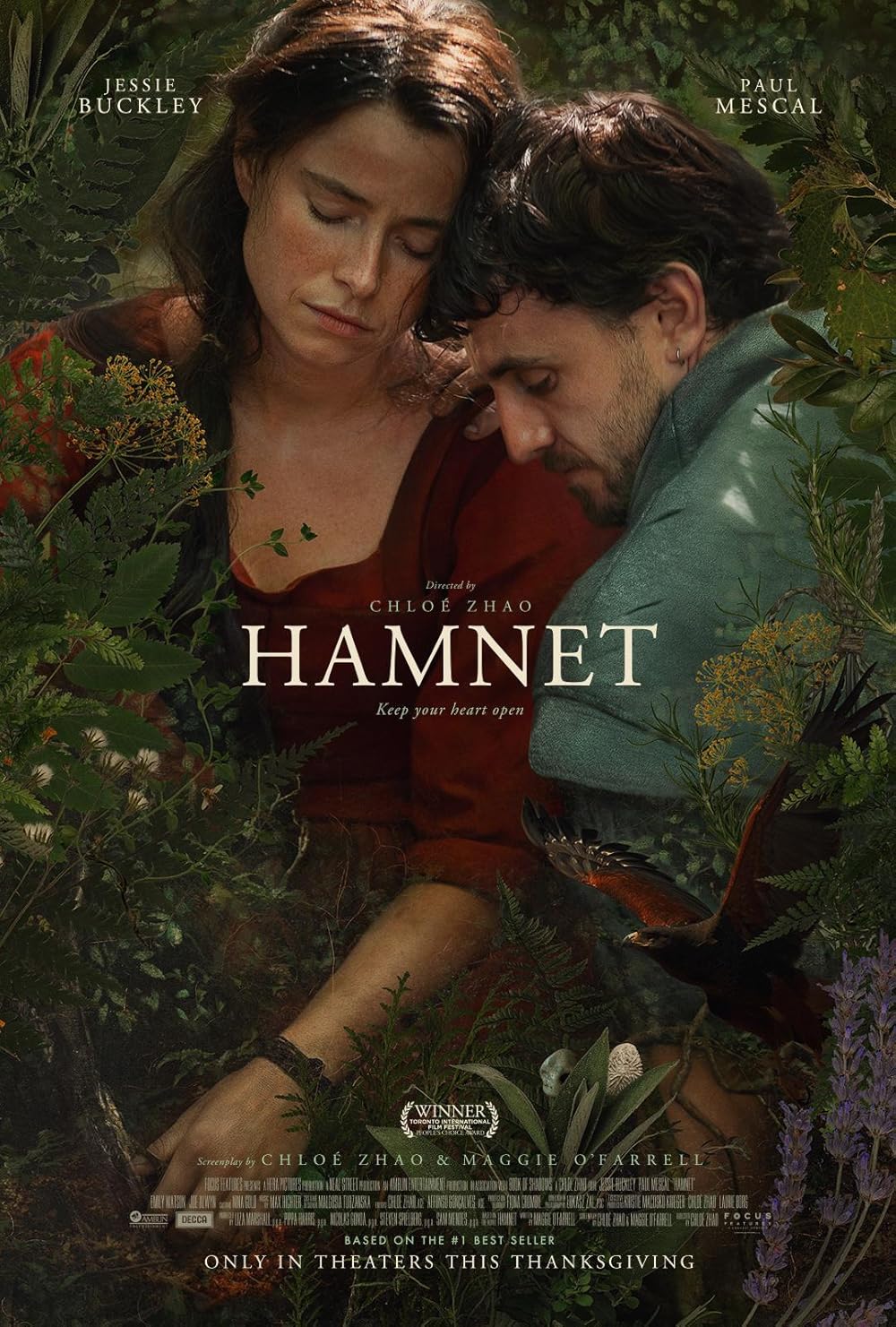

Todd Most Anticipated #5

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

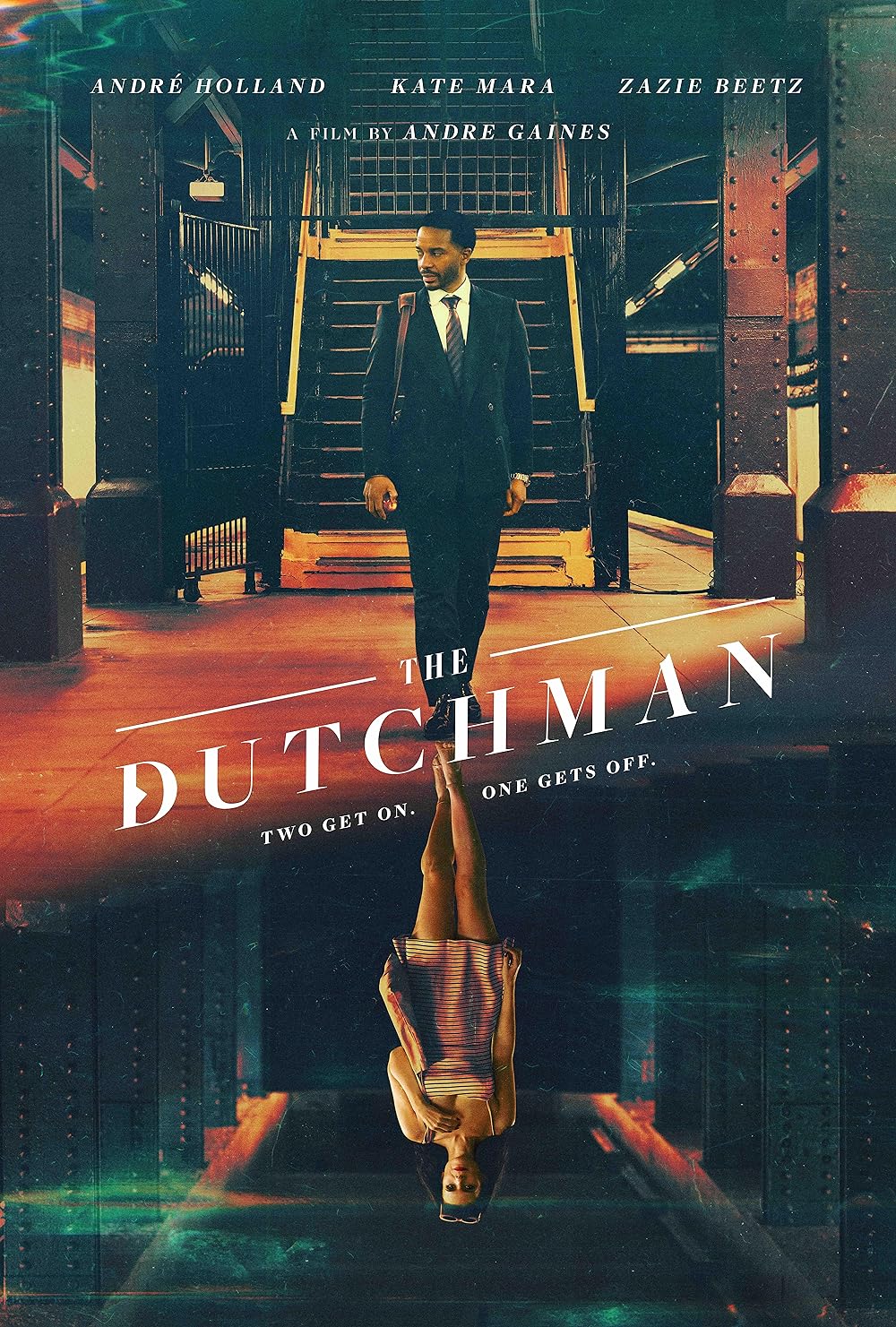

10th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

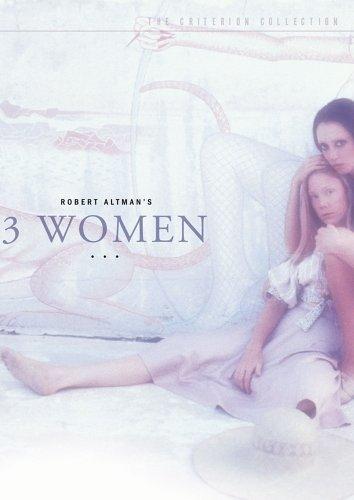

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Zach |

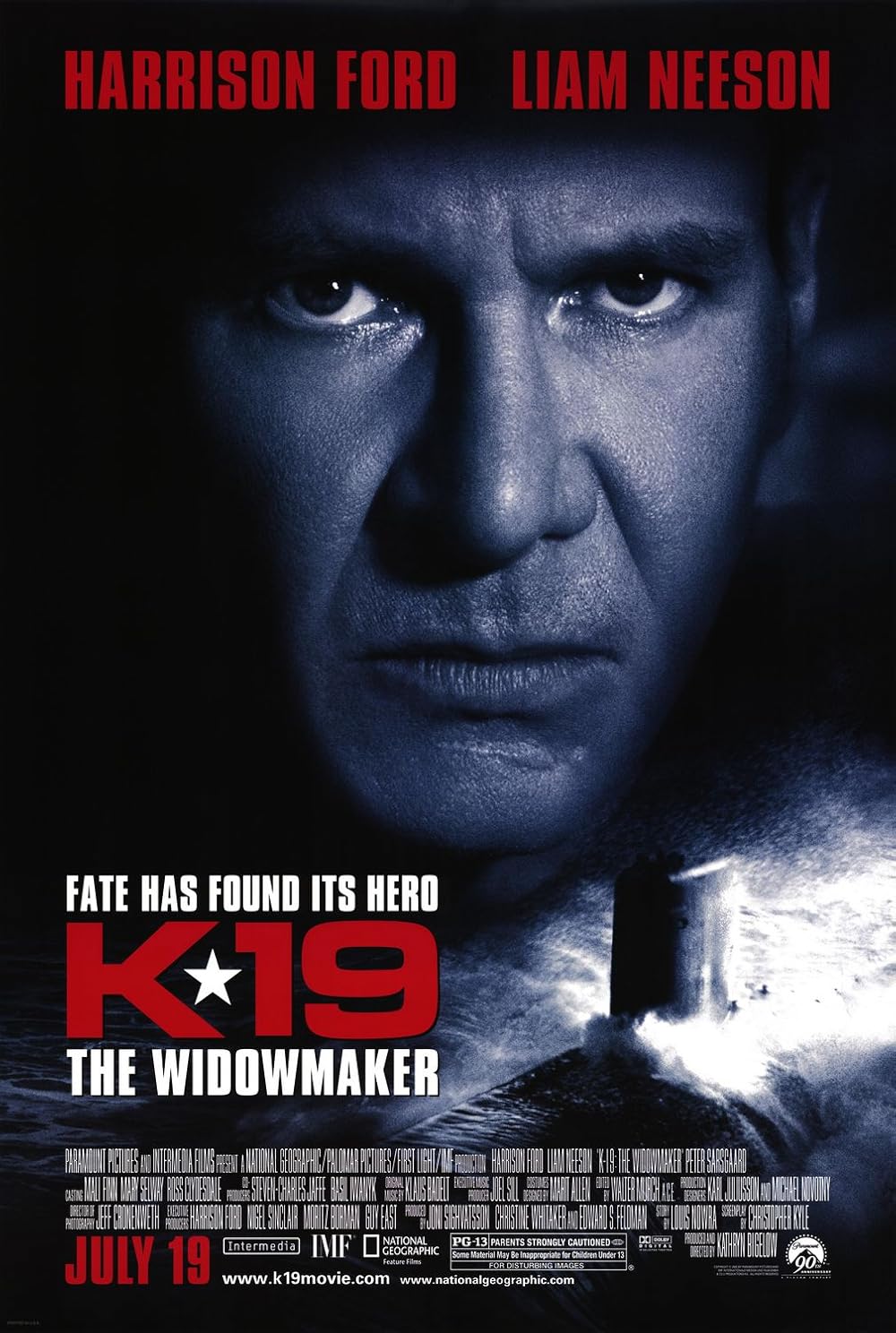

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

2027 Oscar Predictions: Jan.

Written Article - Todd |

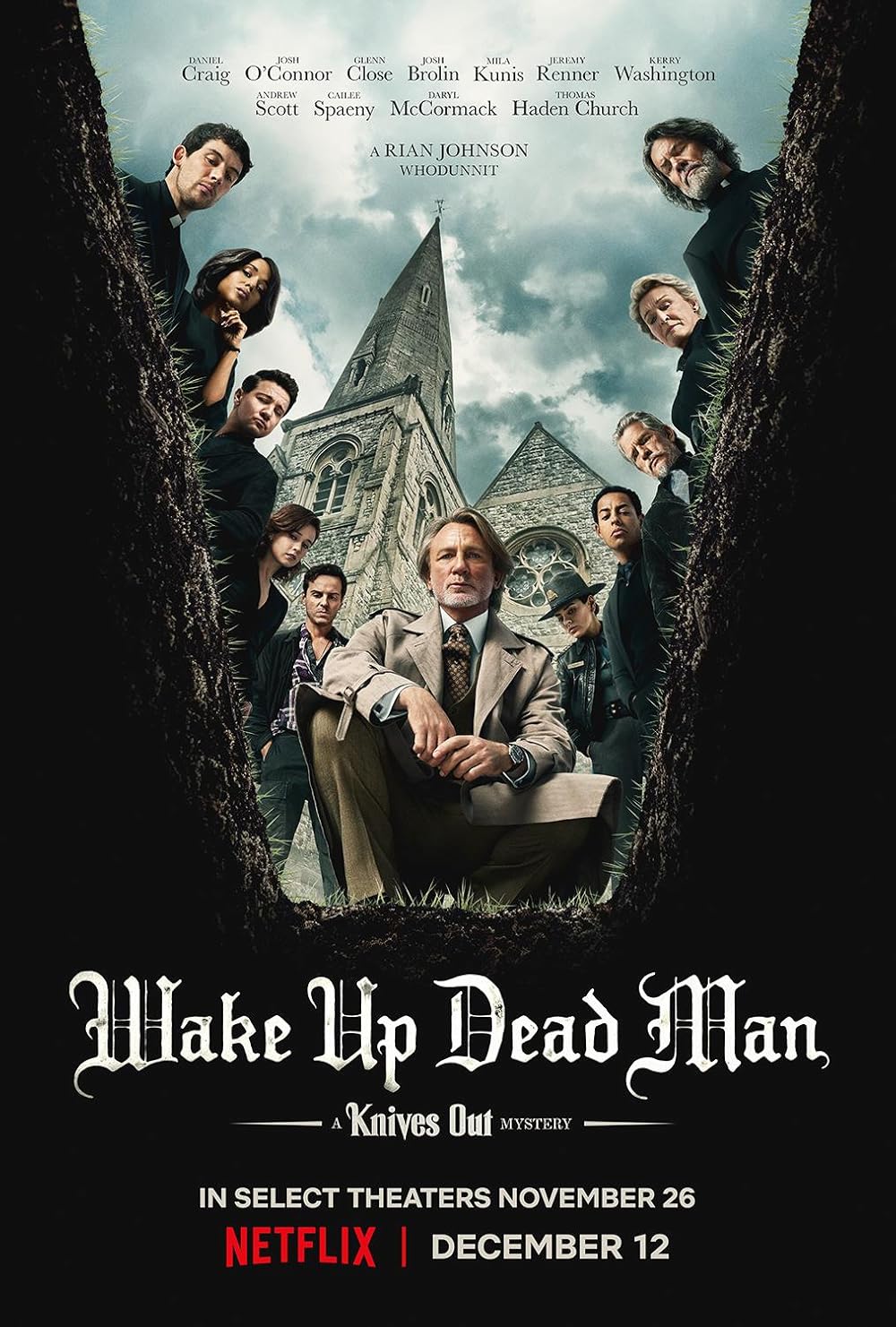

Terry Most Anticipated #2

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

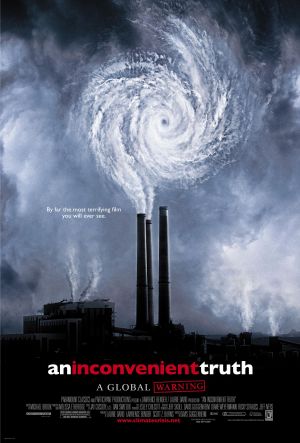

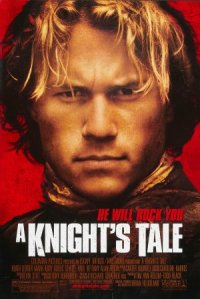

20th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Trivia Review - Adam |

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Terry |

25th Anniversary

PODCAST DEEP DIVE |

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Terry |

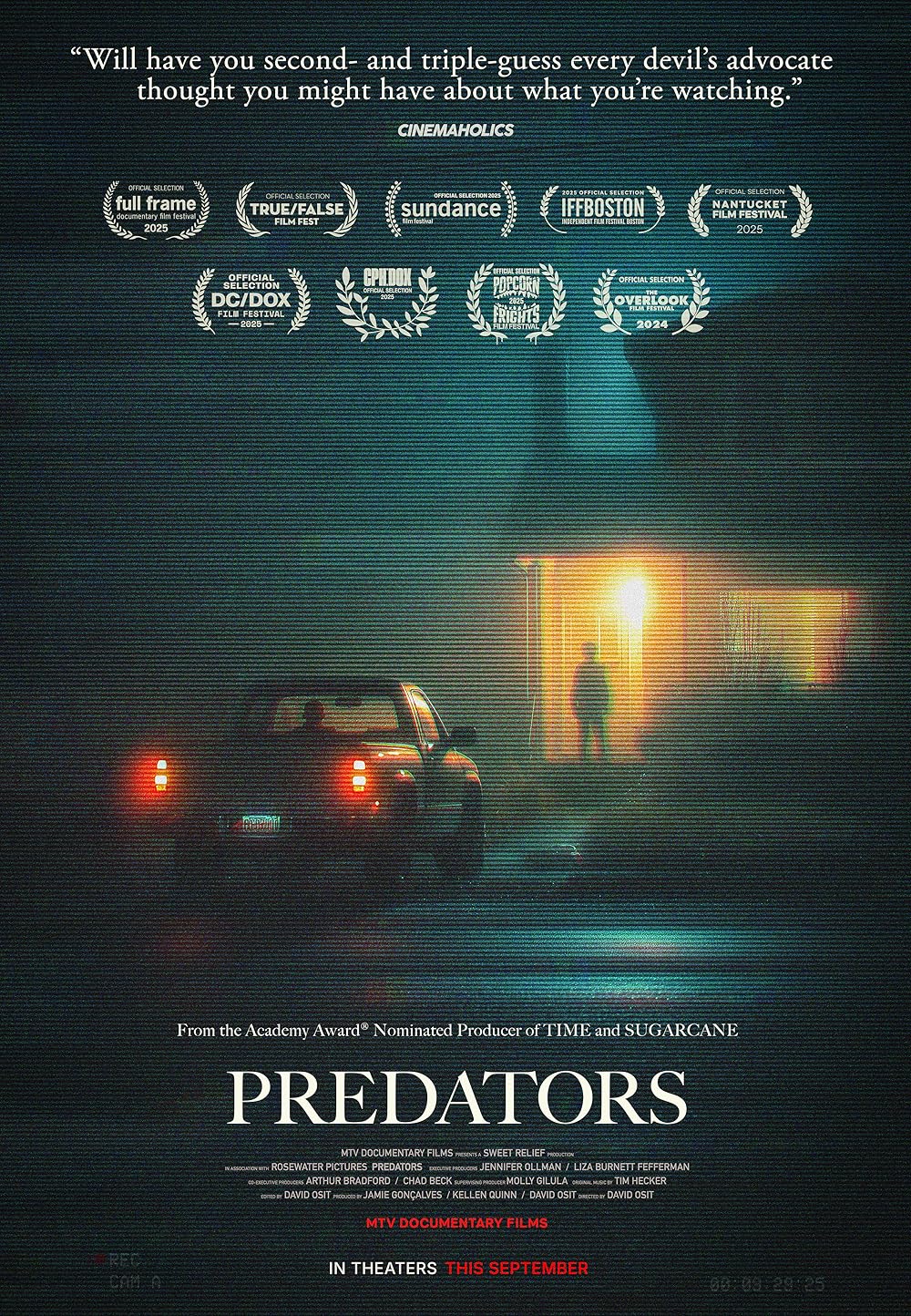

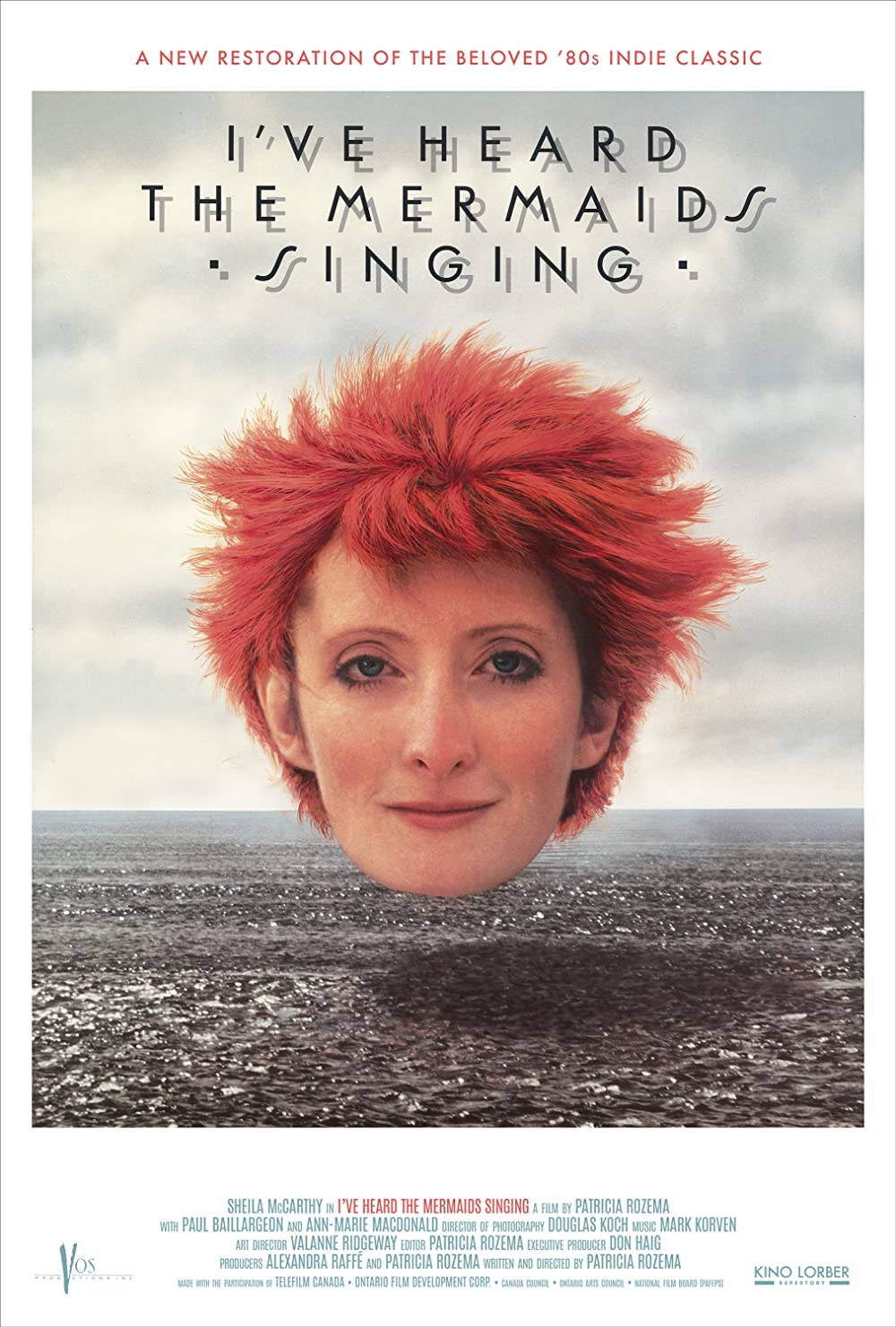

Indie Screener Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

|

|

|