|

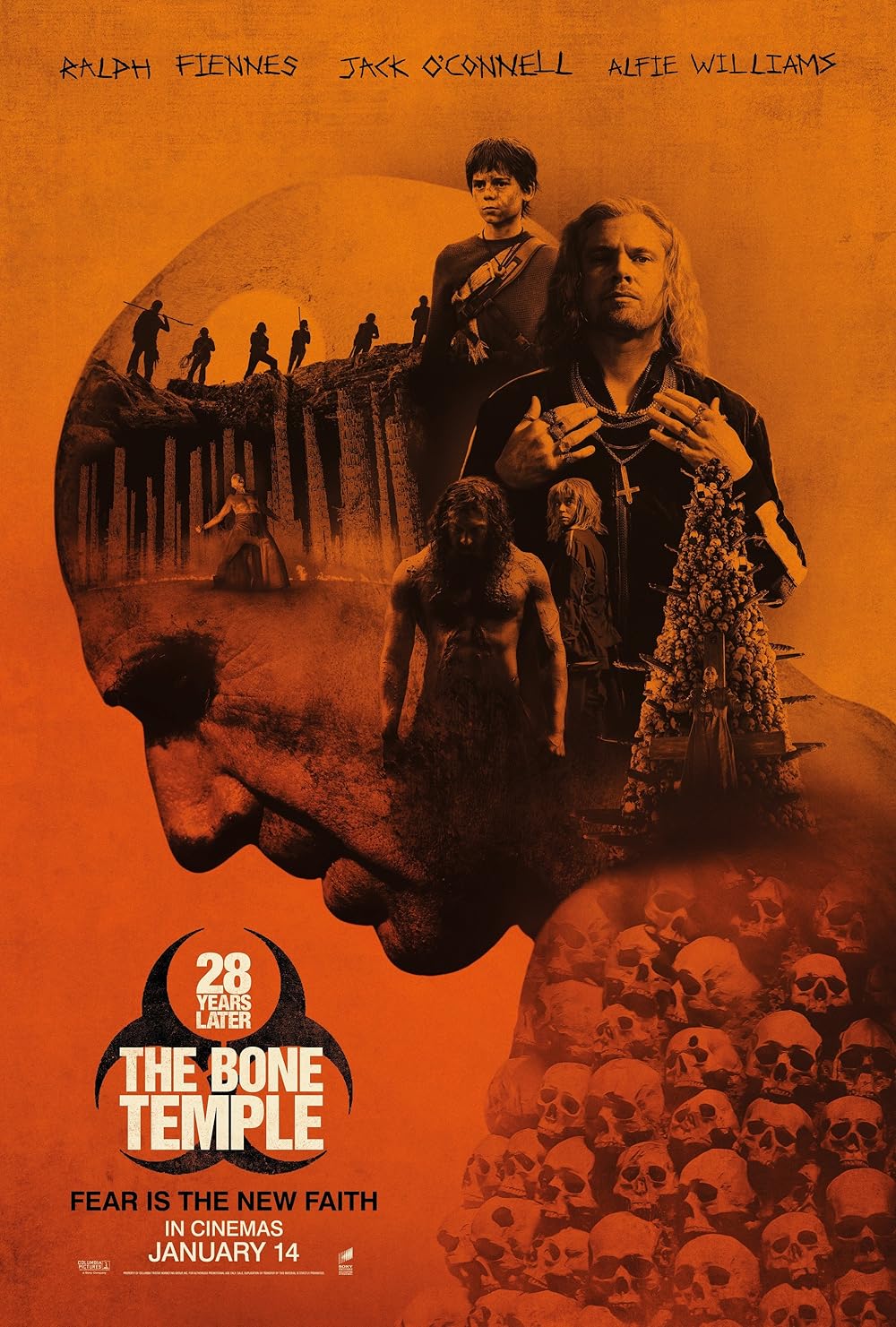

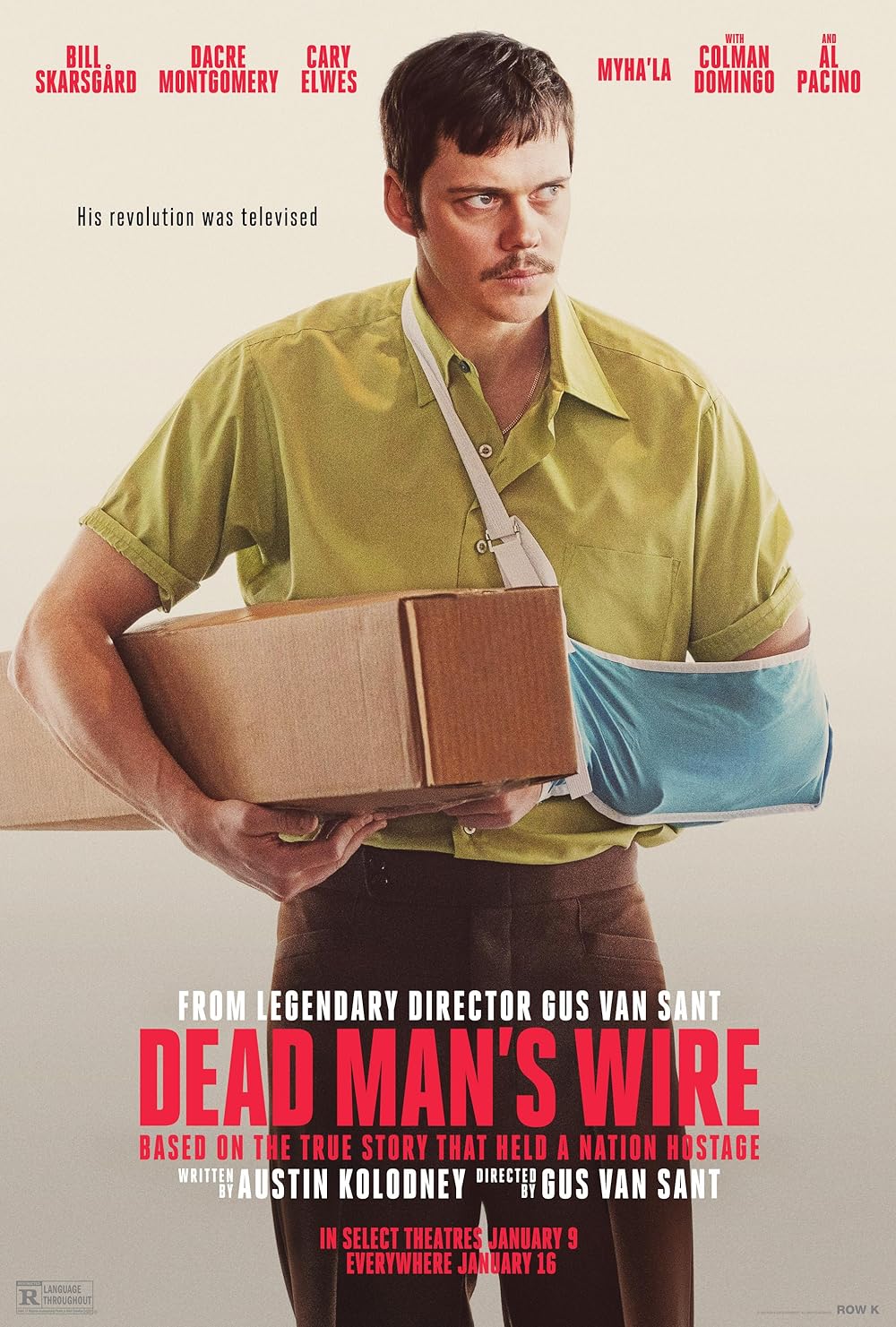

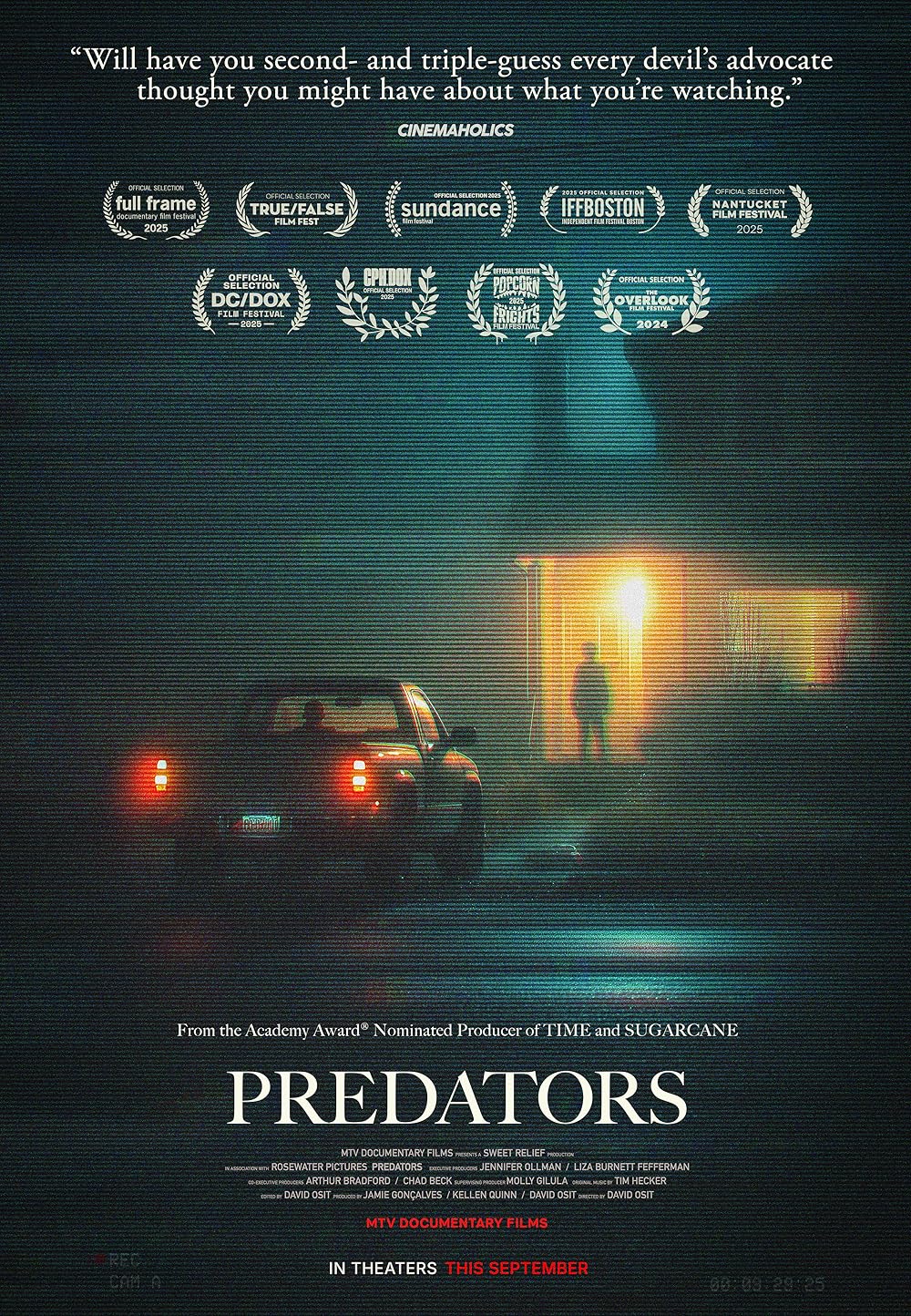

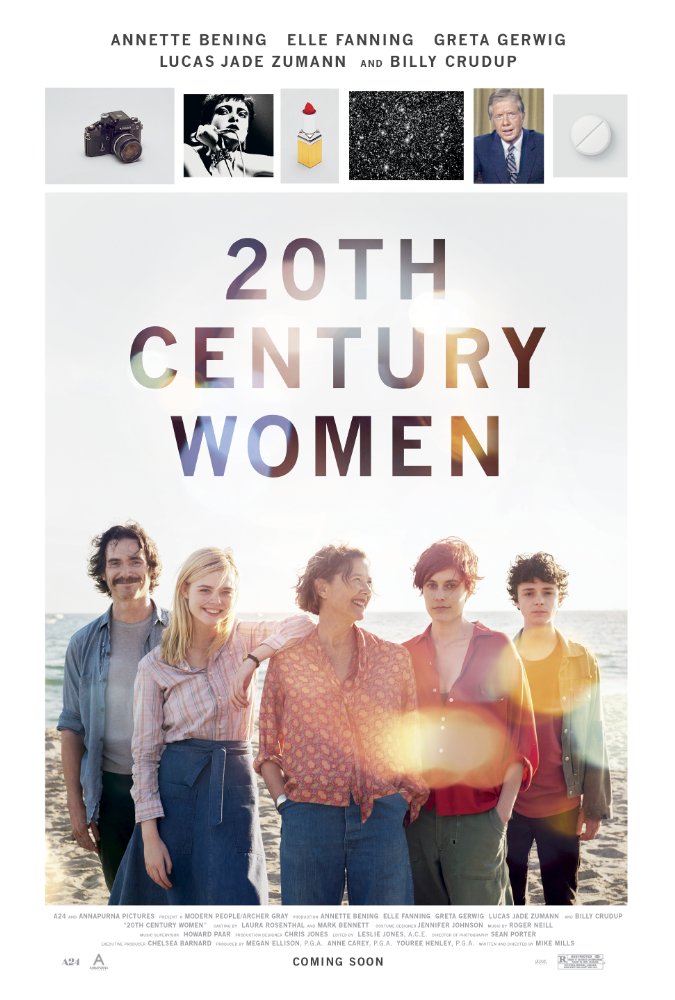

New

Releases |

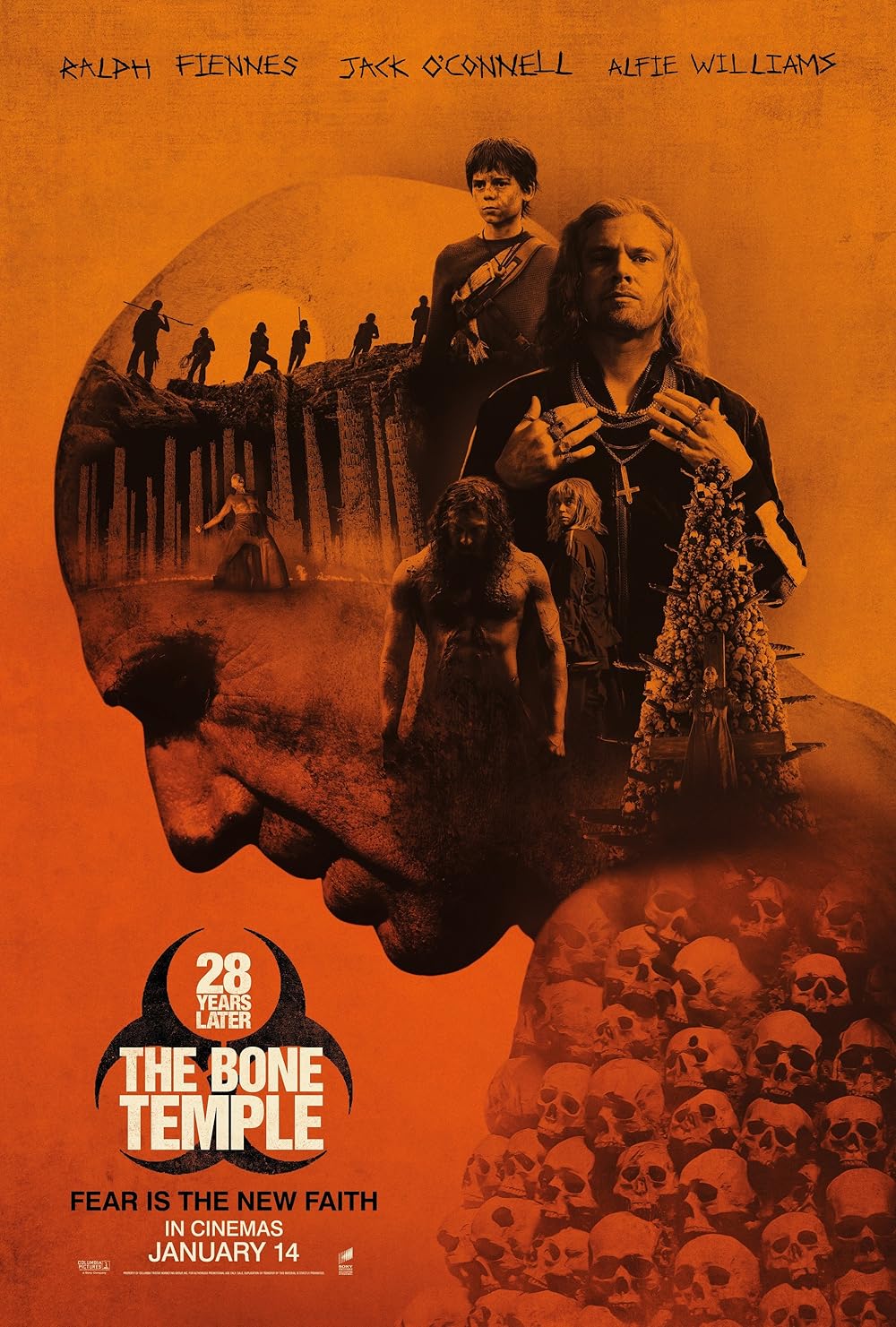

January 16, 2026

|

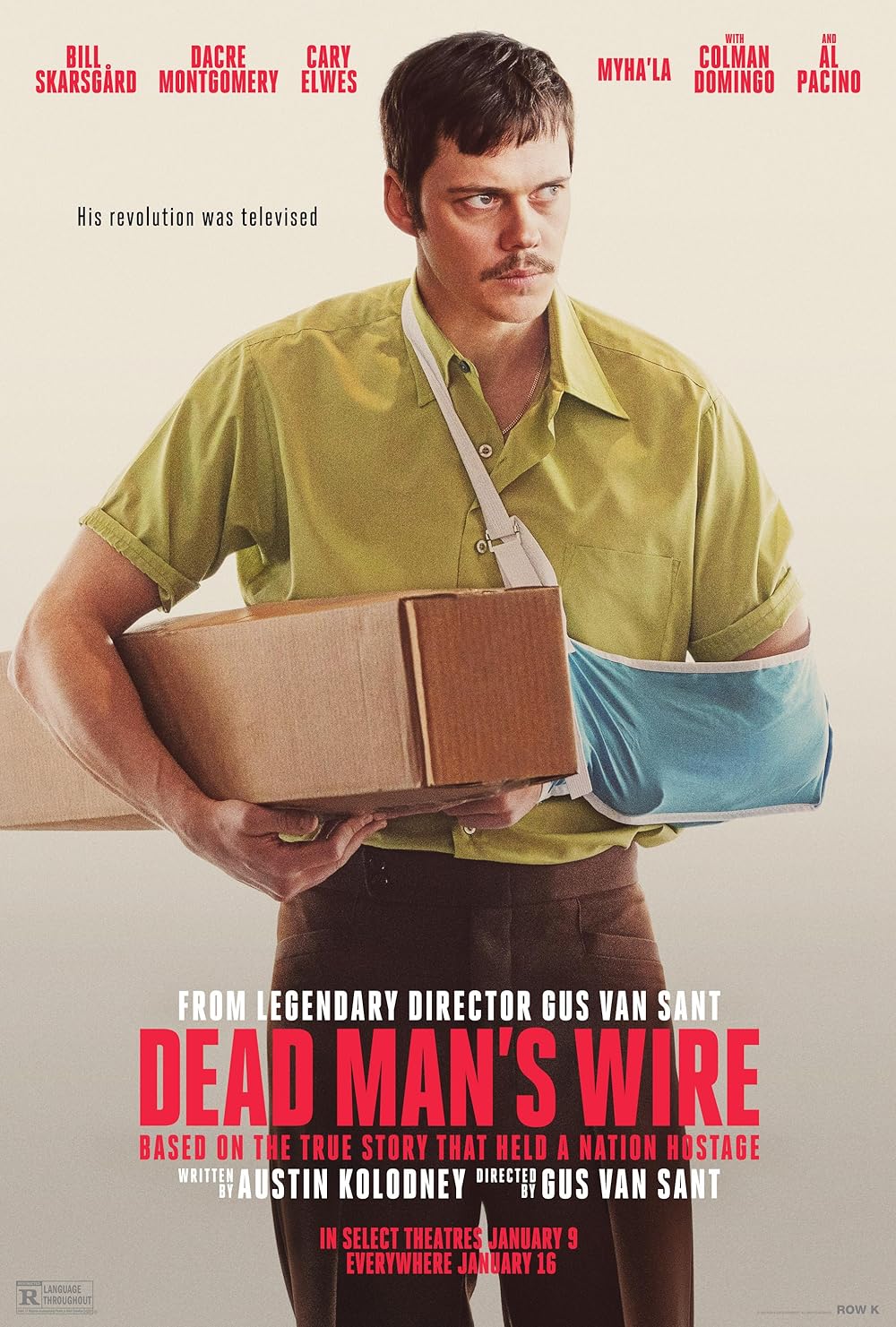

January 9, 2026

|

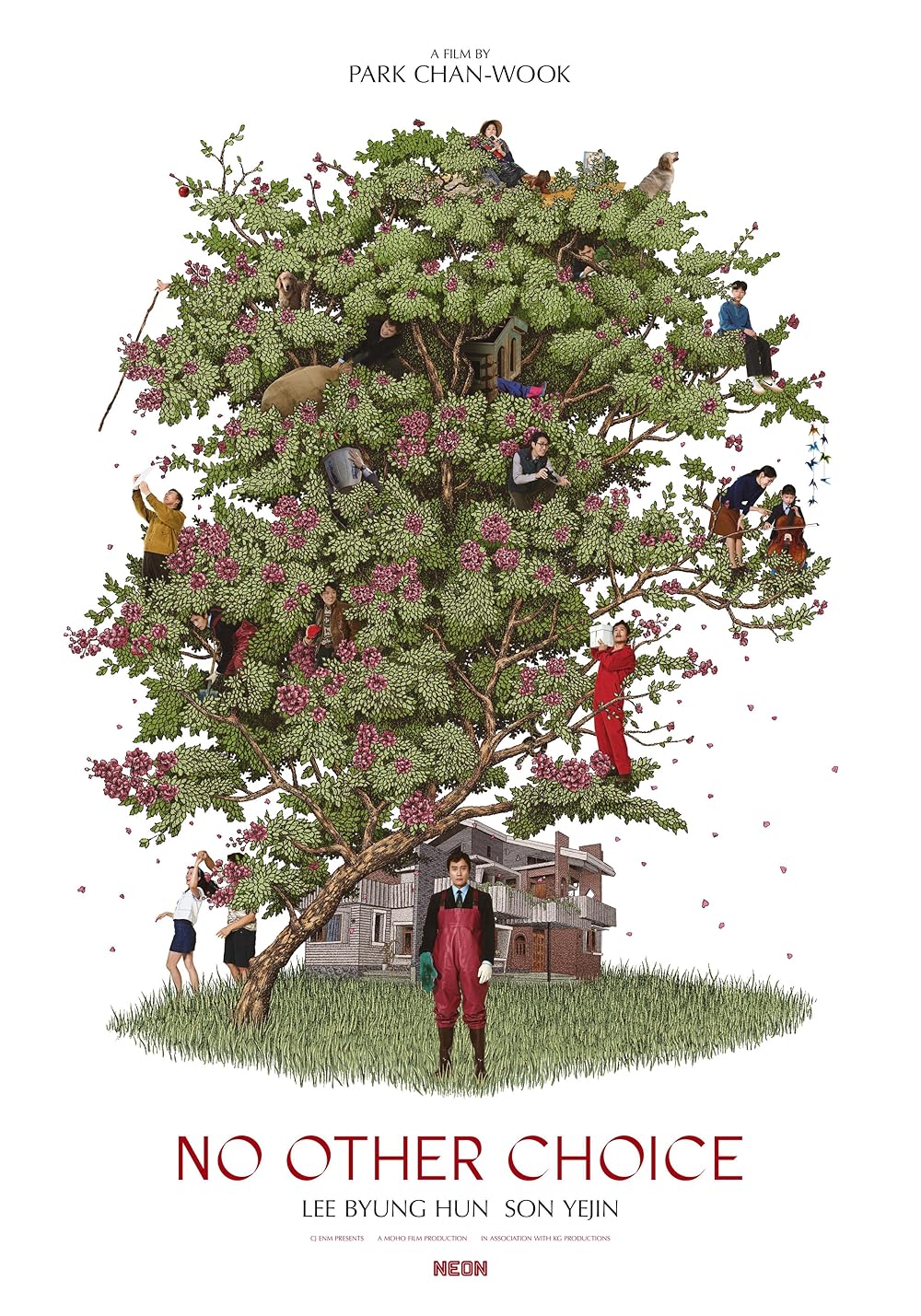

January 2, 2026

|

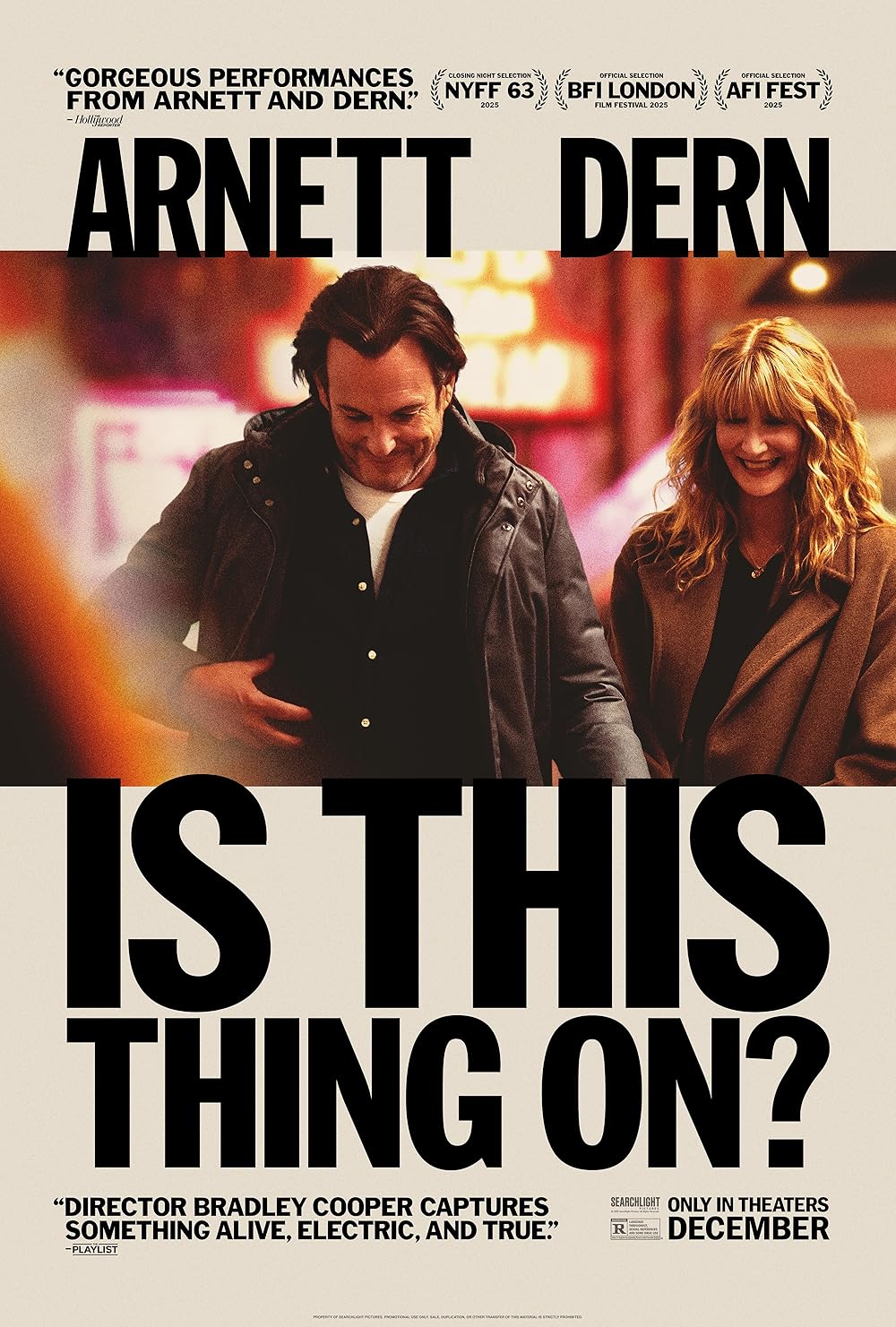

December 26, 2025

|

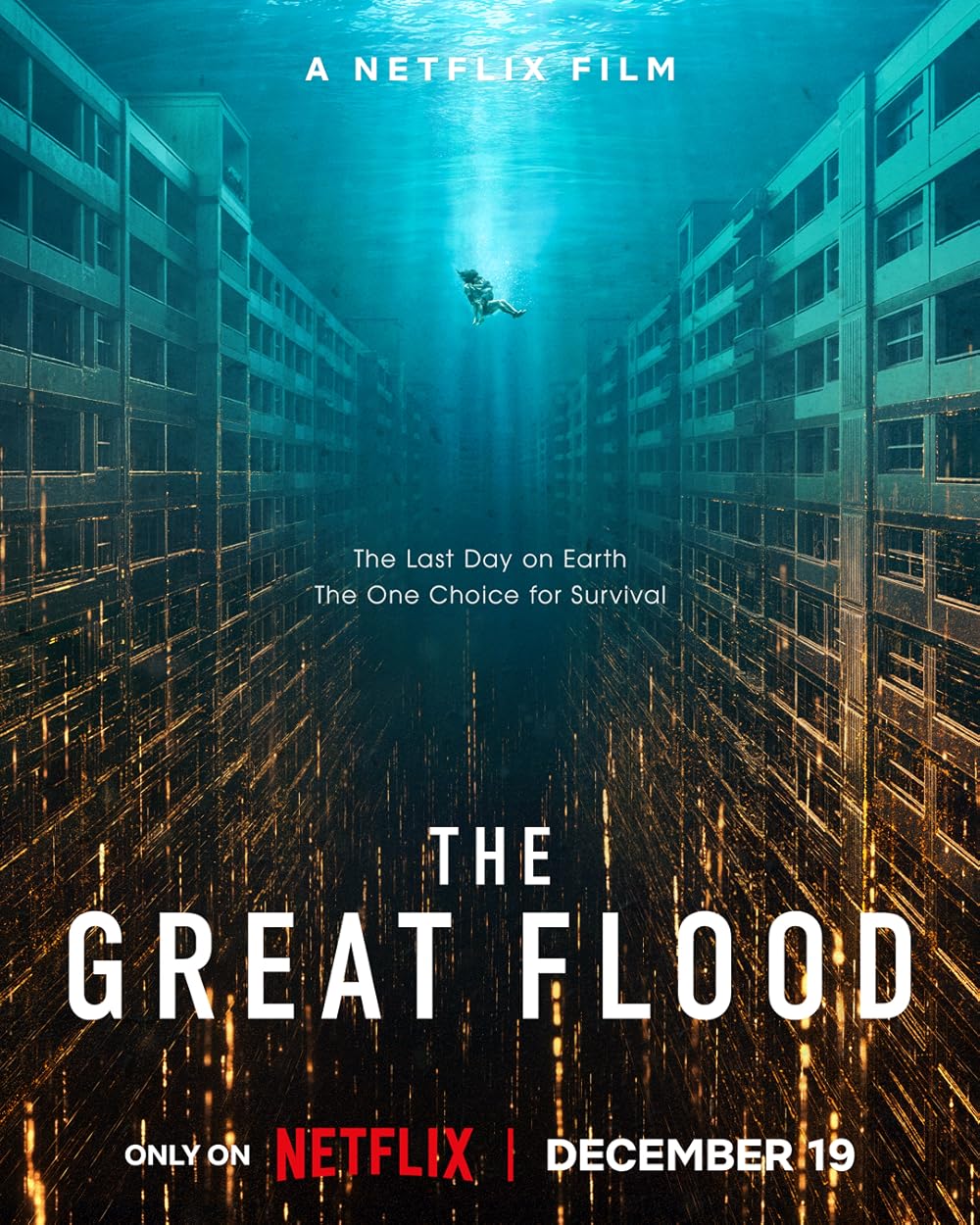

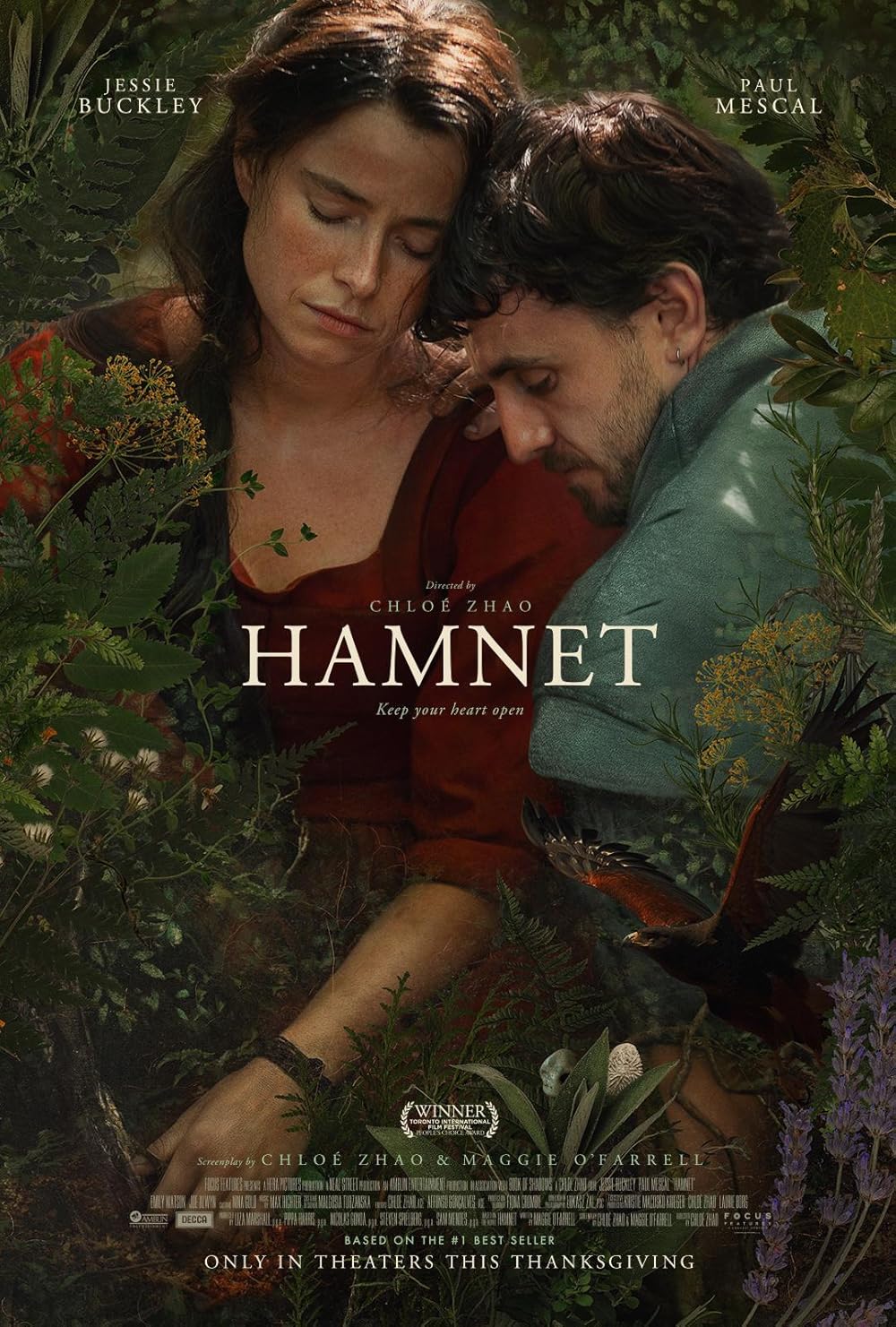

December 19, 2025

|

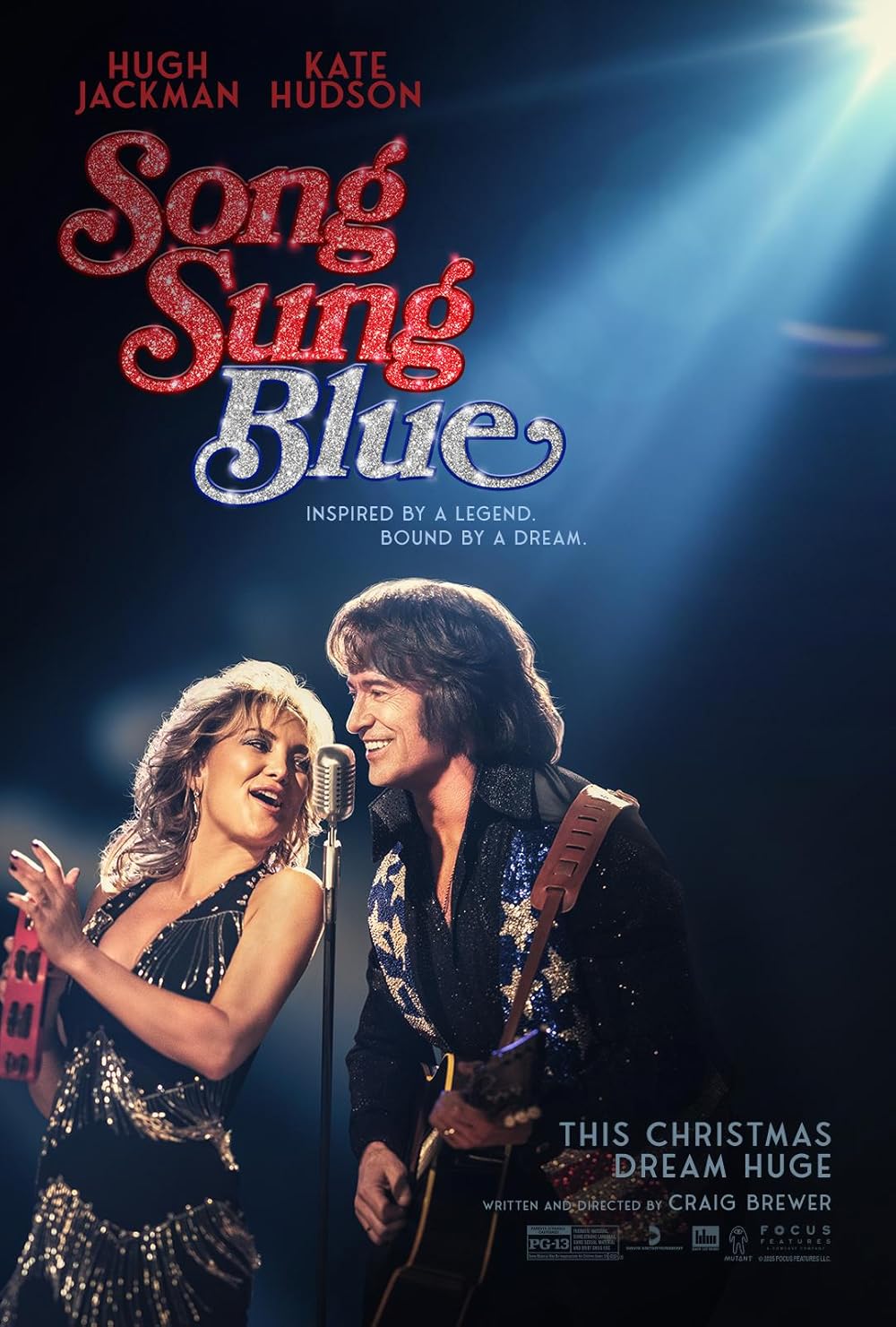

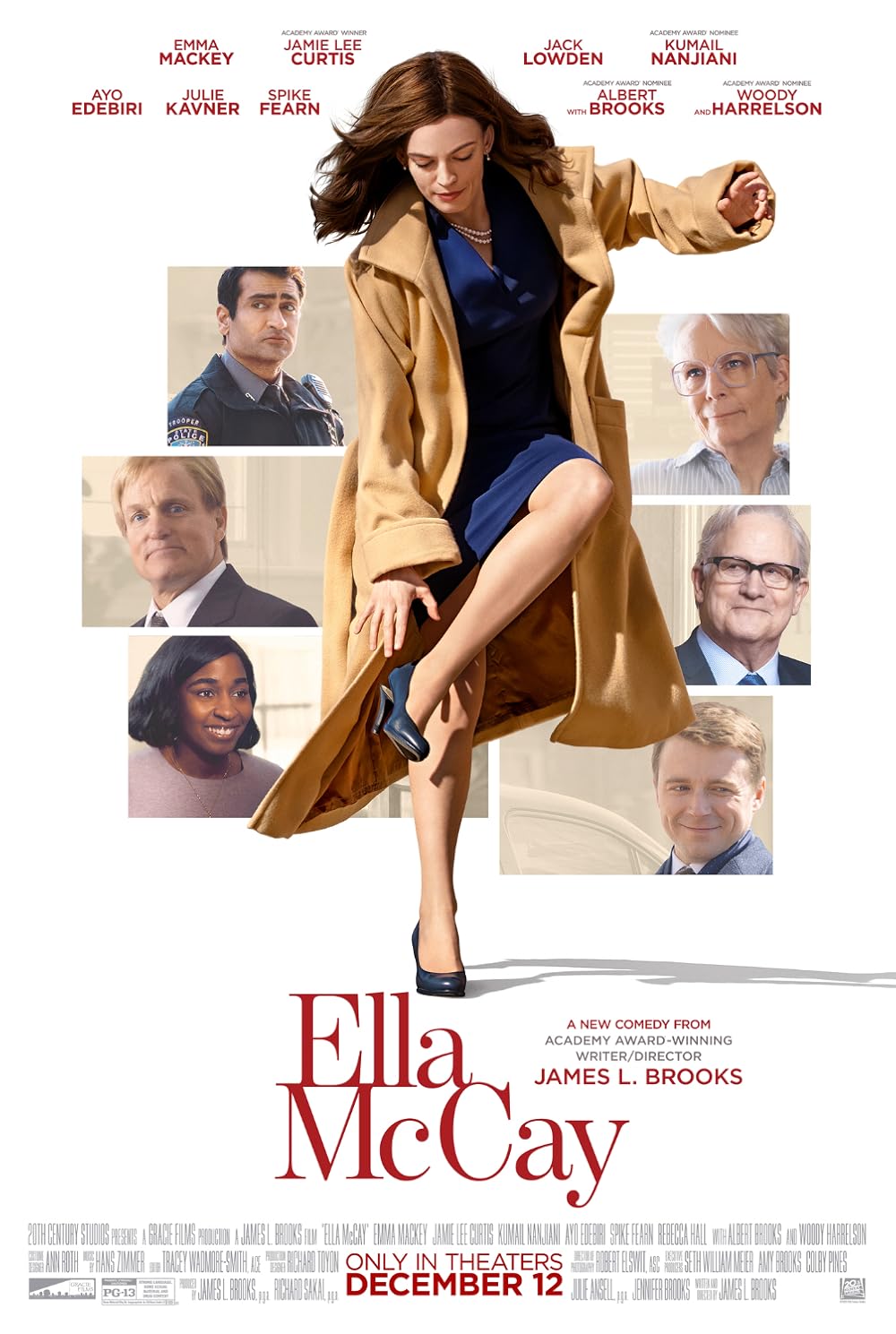

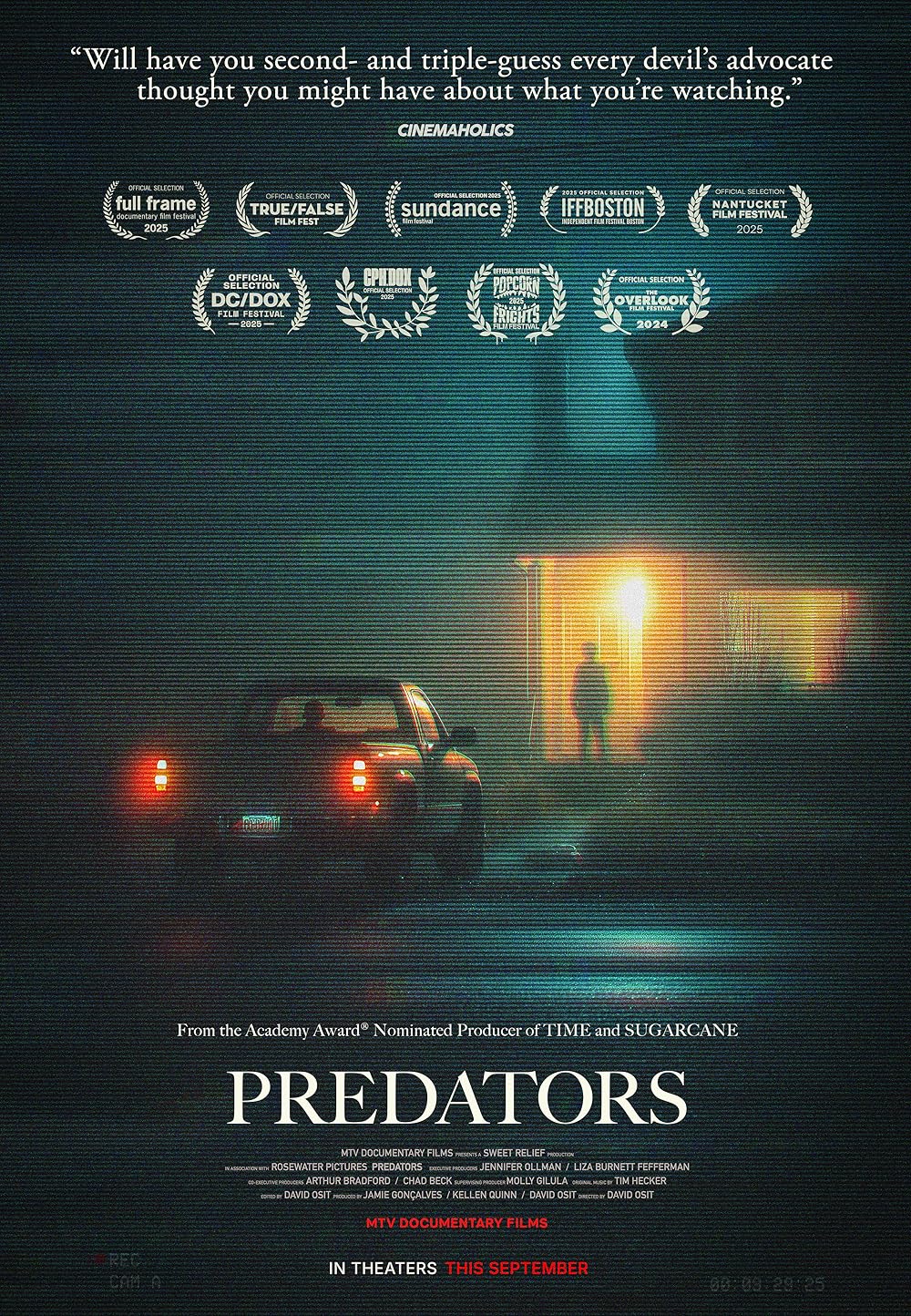

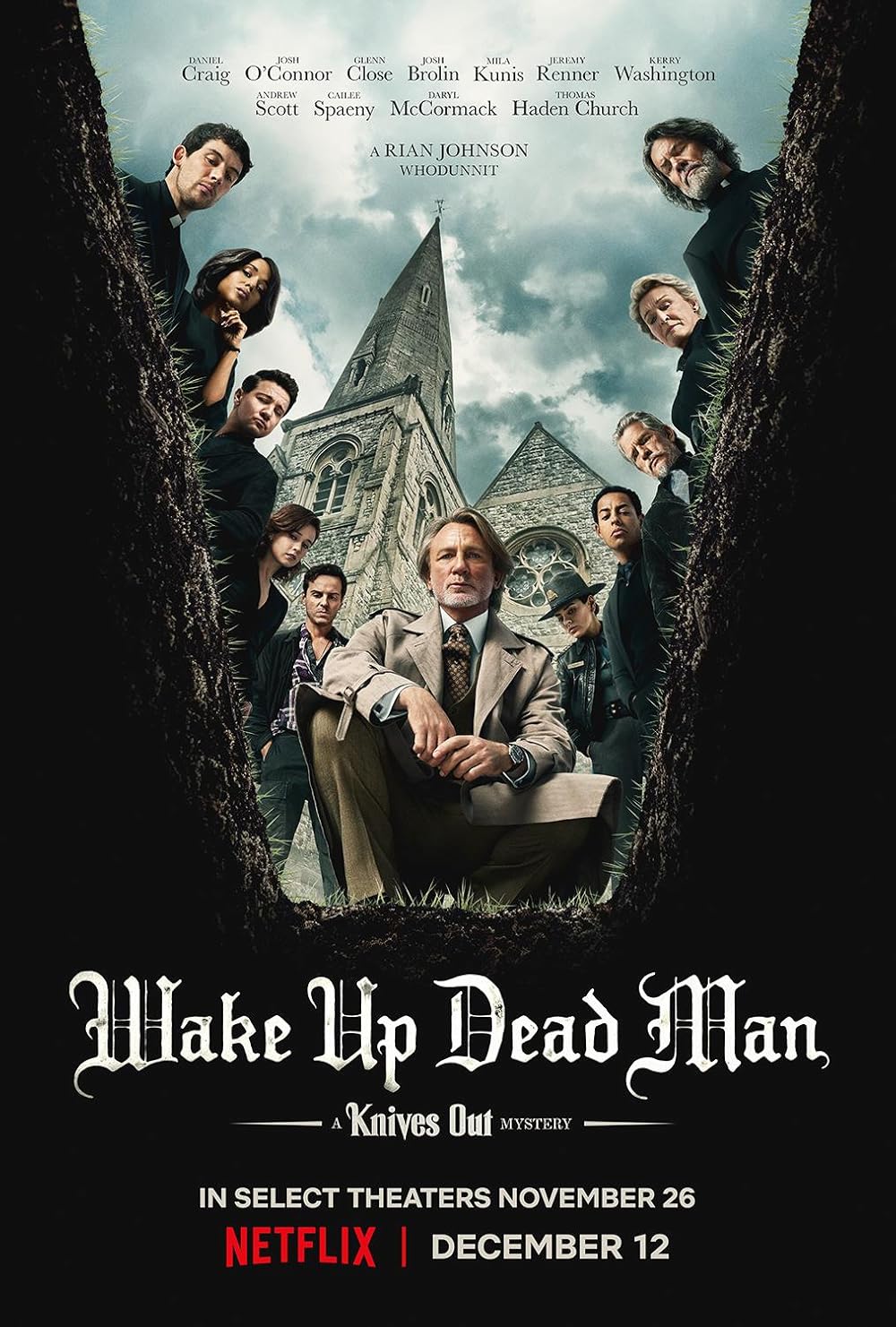

December 12, 2025

|

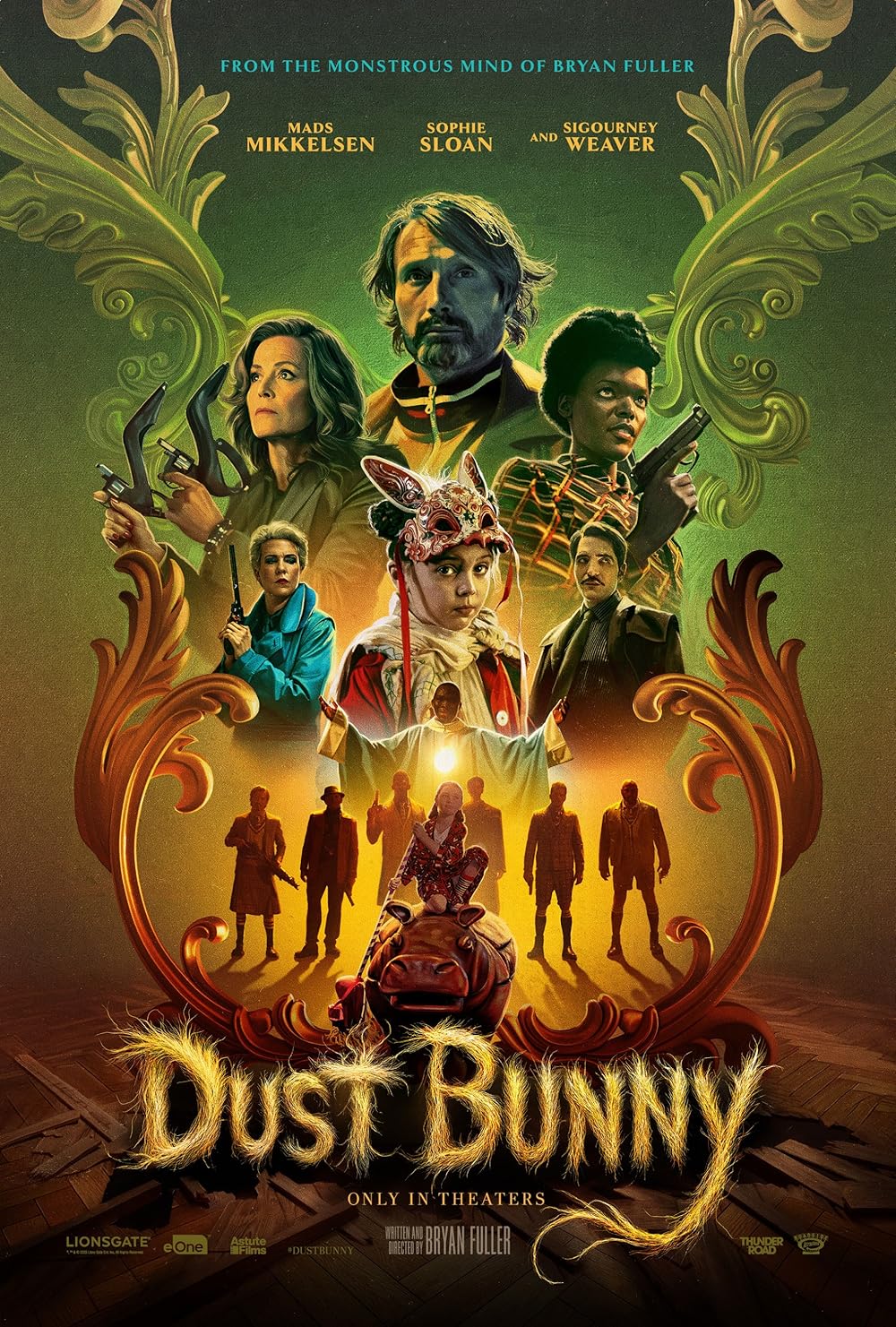

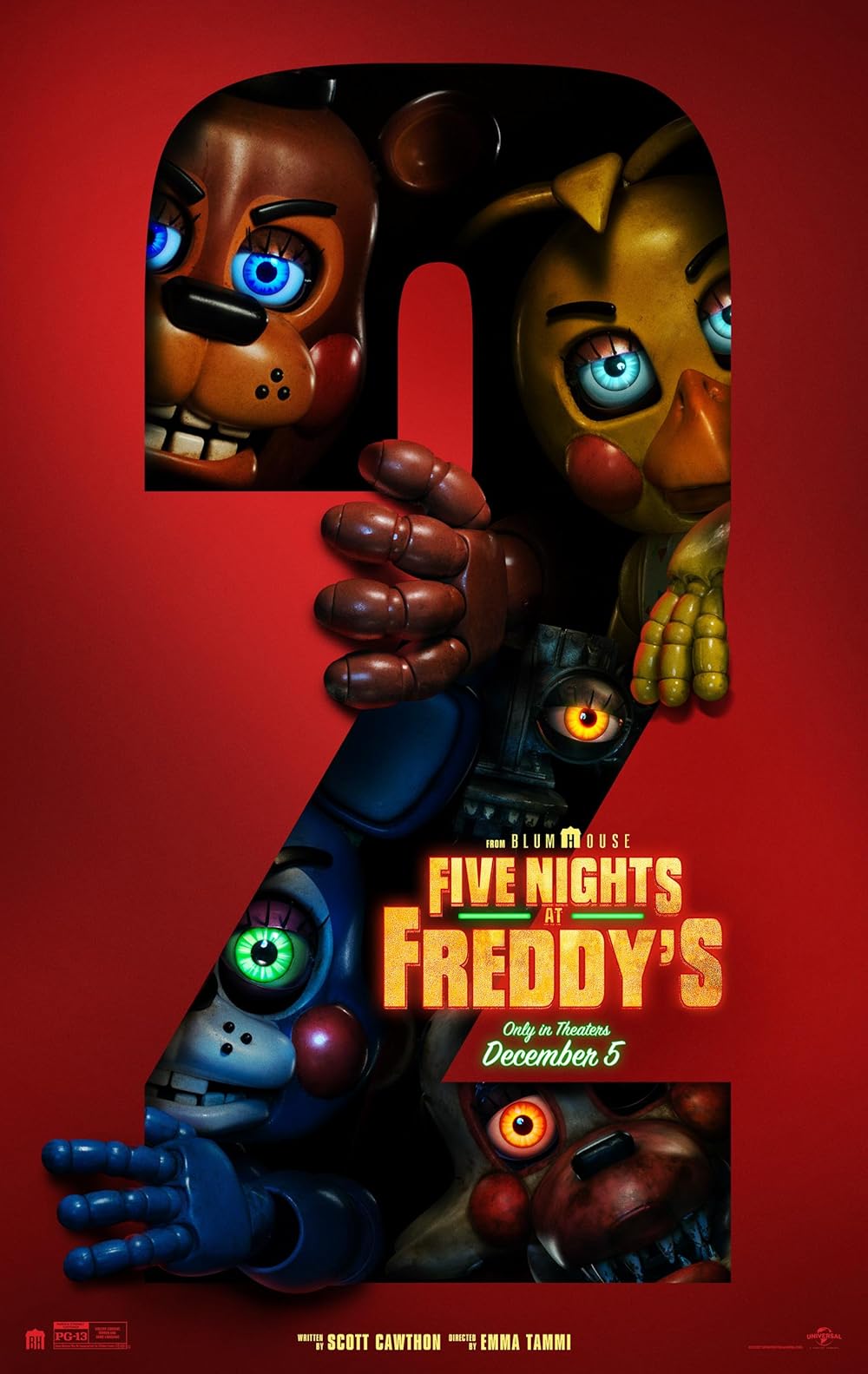

December 5, 2025

|

|

|

|

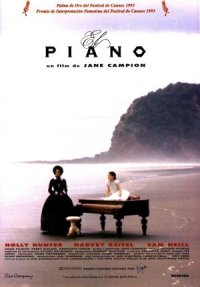

The Piano

(1993)

Directed by

Jane Campion

Review by

Zach Saltz

In Jane

Campion’s

The Piano (1993),

the outwardly nebulous concept of a woman’s will serves as the central

basis for understanding her inwardly repressed psyche.

The word “will” has been prescribed to mean many things -- will

as an auxiliary verb, meaning to enable, or will as a noun, meaning an

ardent desire or wish.

Will

power refers to the strength or capability to withstand hardships.

Nietzsche wrote of an acerbic “Will to Power” serving as the

central basis for the belief that innovators should make their own

pragmatic values.

But the

will of the central woman in

The

Piano has less to do with intrinsic potency of emotion or caustic

control than a sort of supernatural prowess that ultimately determines

her fate.

The will is not

religious, but it has enough power to make its patients (or victims,

depending on circumstance) question its motives just as people question

the presence of an Almighty figure, and by the end of the film, this

woman wonders why her will has let her live.

The woman,

Ada (played by Holly Hunter), is immediately cast as an outsider upon

arrival in the lush forest of New Zealand -- as both a mute, as a Scot,

and (most egregiously) as a woman.

These characteristics naturally beg for discrepancy in initial

appraisal of her: while the native Maoris are at first shocked at her

pallid visage (“Look how pale,” one says about both

Ada

and her daughter, “like angels”), Stewart, her new husband, calls her

“stunted” with a frigid look of disappointment.

This woman does not look like the figure in the photograph he has

studied and subsequently used as a reflector to hastily comb his hair.

Of course how could he possibly be all that responsive to a

mysterious woman he himself called a “dumb creature?” (His rationale for

betrothal is that God, like him, loves dumb creatures, too.)

Invariably

their marriage is a façade, and the only proof of its existence comes in

the form of a shabbily-shot photograph of bride and groom passively

sitting next to each other in the midst of a downpour.

Ada

wears a silly gown that she defiantly rips off afterwards, and Stewart

peeks through the camera, confident in his steadfast grasp of the time

and setting.

This motif of

peeking secretly through a hole will reverberate in a later scene when

Stewart looks through a peephole in Baines’ wall to find a sight not

quite so inhibited and under control.

The idea of control was very important in repressive Victorian

society, and Ada’s illicit capitulation to Baines’ sexual blackmail

coupled with the atmosphere of uninhibited Maoris represent stark

backlash to the all-too-formal elements of the European society left

behind by its white émigrés.

Stewart

throughout the film seems profoundly unaware that he is living in rustic

New Zealand rather than aristocratic England; he is so disillusioned

that he cannot even understand the significance of the sacred Maori land

he so vehemently desires.

“What do they want the land for?” He unabashedly laments to Baines.

“They don’t do anything with it.

They don’t cultivate it, they don’t burn it back, nothing.

How do they even know it’s

theirs?”

In his eyes, the

Maoris are savages, with their immoral nakedness and rambunctious

sexuality.

Stewart asserts

his cultured manners by wearing clean shirts and pants and a noble yet

ultimately pitiful top hat.

Indeed, hearty scenes such as when Ada and Flora carefully

tread through a massive pile of mud illustrate a rugged and bucolic

atmosphere that reflect the insidiousness of Stewart’s proclamations of

English male sensibility and decency.

Baines, on

the other hand, is a precursor to what Joseph Conrad must have been

imagining when he created the character Kurtz in

Heart of Darkness.

Here is a man who does not attempt in any way to announce his

European roots, and instead fully assimilates into the Maori culture,

speaking their language and painting his face with their symbolic

illustrations.

His untidy

clothes reflect his dismissal of “cultured society,” and indeed, an

important element of

The Piano

(with its obvious Victorian roots) is the way in which clothes

reflect the suppressive nature of hierarchical roles in the closed

society.

Ada

wears a tightly-fit corset with a bustle, and a hoop skirt that extends

far beyond her tiny legs.

This leads to the film’s most erotically-charged moment, when the

scruffy Baines, beneath the piano, spots a lone tiny hole in the

fittings that sticks out like a sore thumb; and as he covers up the hole

with his fingers, the viewer reads this as a sublimation of tender

aggression toward the harsh formal society in which both characters have

been deemed outcast.

One motif of

The Piano is that of

bargaining.

Besides the

negotiations aforementioned between Stewart and the Maoris, Ada is shamelessly used as a personal

bargaining tool of Stewart to acquire 80 acres of land -- by agreeing to

give Baines his wife’s piano.

When Ada begins to feebly teach

Baines piano lessons, their sessions quickly turn into sensuous

lovemaking as a result of a lurid offer to return the piano to its

rightful owner.

The

transformation of Ada is most clearly seen

in her changing attitude toward Baines; at first, she is repulsed by him

and is shocked by his brash attempts to caress her neck and “lie with

him,” but there is no denying the economical benefits of succumbing to

his fantasies (there are, after all, only 36 black keys on the piano).

But later when Baines gives the piano to Ada (as both a gift and

a poignant artiface of a relationship he knows cannot last -- “It’s

making you a whore and me wretched”), she insolently returns to his hut;

for now it is not her beloved piano she seeks, but comfort -- both

friendly and sexual -- that only Baines can offer her.

Hence, the initial illicit sexual bargaining beginning as a

masochistic master-slave antagonism has blossomed into a renaissance of

a deeper sense of necessity and greater self-worth.

In that sense, it is an exchange of wills -- the will to dominate

through frivolous bargaining superseded by the will to love and satisfy

in the idylls of mutual affection.

Of the many

dichotomies in the film, the most pervasive lies between reality and

illusion.

While the film

itself is mostly void of formalistic elements (the only noticeable

examples are the employment of Ada’s voiceover and the curious animation

when Flora speaks of her father to Aunt Moorag), the invisible presence

of Ada’s will always adds a supernatural atmosphere to the story, as if

we are being told a legend or a fable out of place and time unblemished

by modern encumbrances.

As

in Gothic literature, pathetic fallacy serves as a barometer of emotions

being played out, as the black rain begins to fall when Stewart

discovers

Ada’s

gift to Baines (the “key” to her heart).

An earlier scene on the sunny beach featuring Flora performing

ecstatic cartwheels represents the ephemeral joy that is found in the

liberating yet sparse wide open spaces of the island.

And the underwater images toward the end, shot by director

Campion in a wonderfully unusual stop-motion filming technique,

represent Ada’s “underwater grave” beneath a sea of

rapture -- not waving but drowning, to channel the famed Stevie Smith

poem.

And that

leads to the question of the ending, which some critics and viewers

argue makes the film actually lose a certain profundity by being too

conventional and “happy.”

In a story of such stark, lucid imagery and atmosphere, the “happily

ever after” epilogue may seem oddly out of place.

When considering this, I am reminded of what Ursula Le Guin once

wrote: “The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants

and sophisticates, of considering happiness something stupid.

Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting” (336).

But the characters of

The

Piano have encountered so many struggles over the course of the film

that the viewer is left with nothing but a fervent sense of hope that

the story’s resolution will find them at a happy place for once.

Campion is keenly aware, however, of the sharp critical

repercussions of a traditional happy ending to the stoic atmosphere the

film has so meticulously maintained, and wisely chooses instead to focus

the last images of

The Piano

on the stunning capabilities of Ada’s will to at once seemingly end her

life while sparing it the very next moment.

This ambiguity of the ultimate path of Ada’s will has led Carol

Jacobs to suggest that

The Piano

has not one or even two, but three entirely discrete endings,

effectively leaving the viewer without the complete and total

satisfaction of the “happy” ending with Ada teaching piano back in

Nelson, but certainly not without some relief that she has been

liberated from her prison on the island.

Despite the initial confusion, we are sure of one thing, as

Ada

so perfectly articulates: that her will has chosen life, simply and

sweetly, and for this, we can surely all be thankful.

Rating:

# 2 of 1993

|

|

New

Reviews |

Reactions to the Nominations

Written Article - Todd |

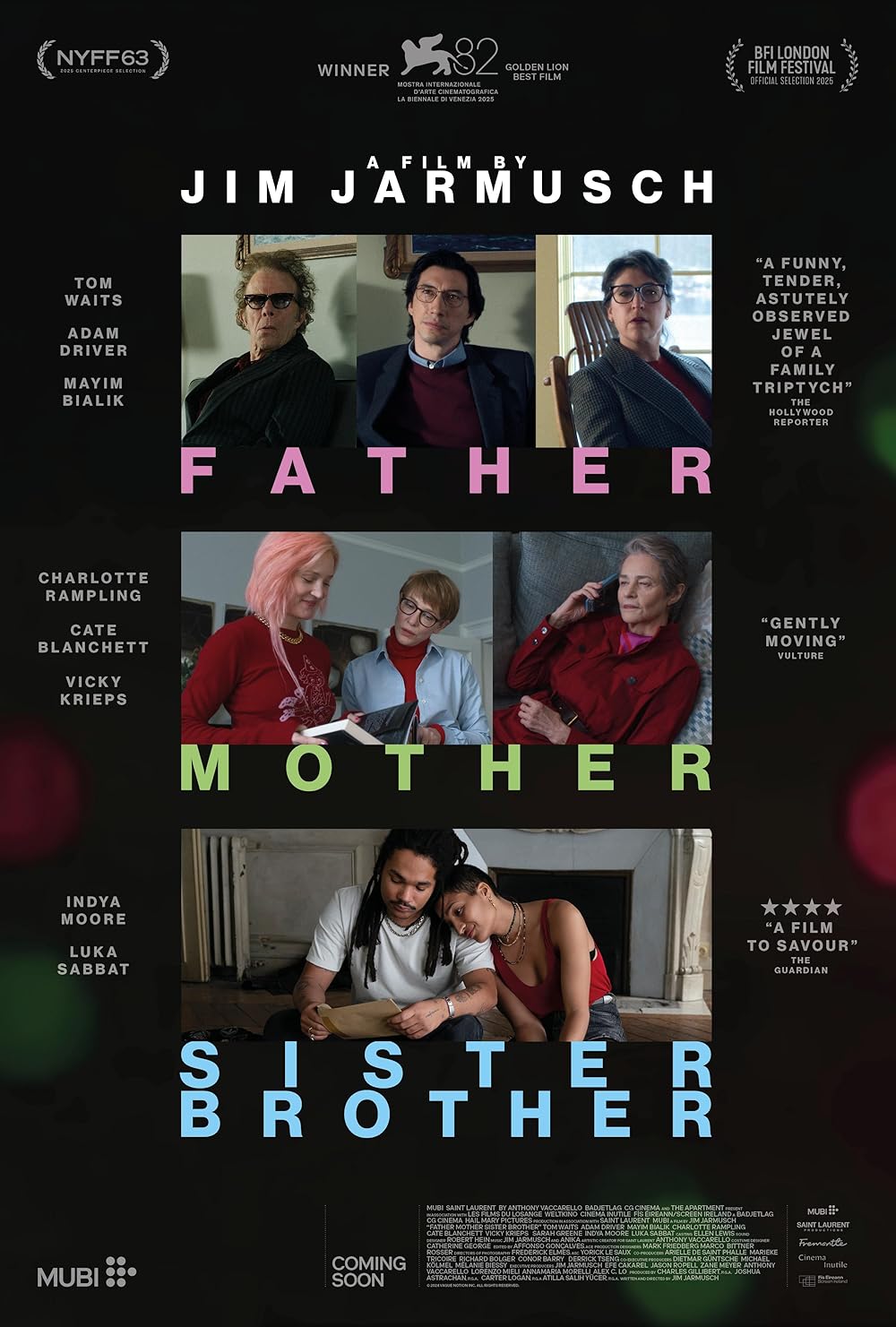

2026 Oscar Predictions: Final

Written Article - Todd |

Todd Most Anticipated #5

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

10th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

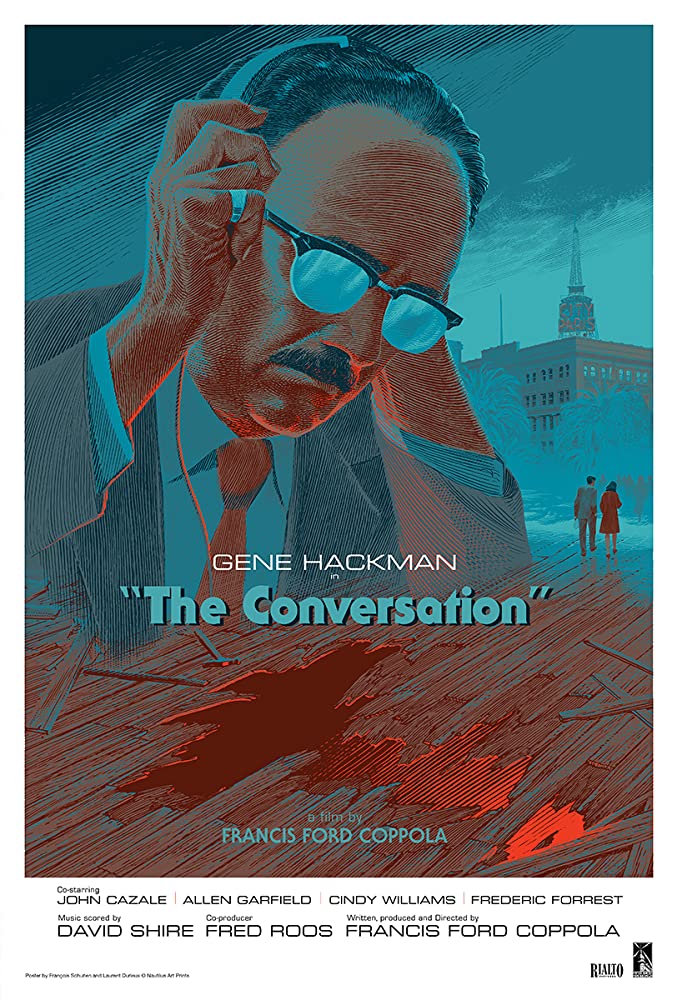

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Zach |

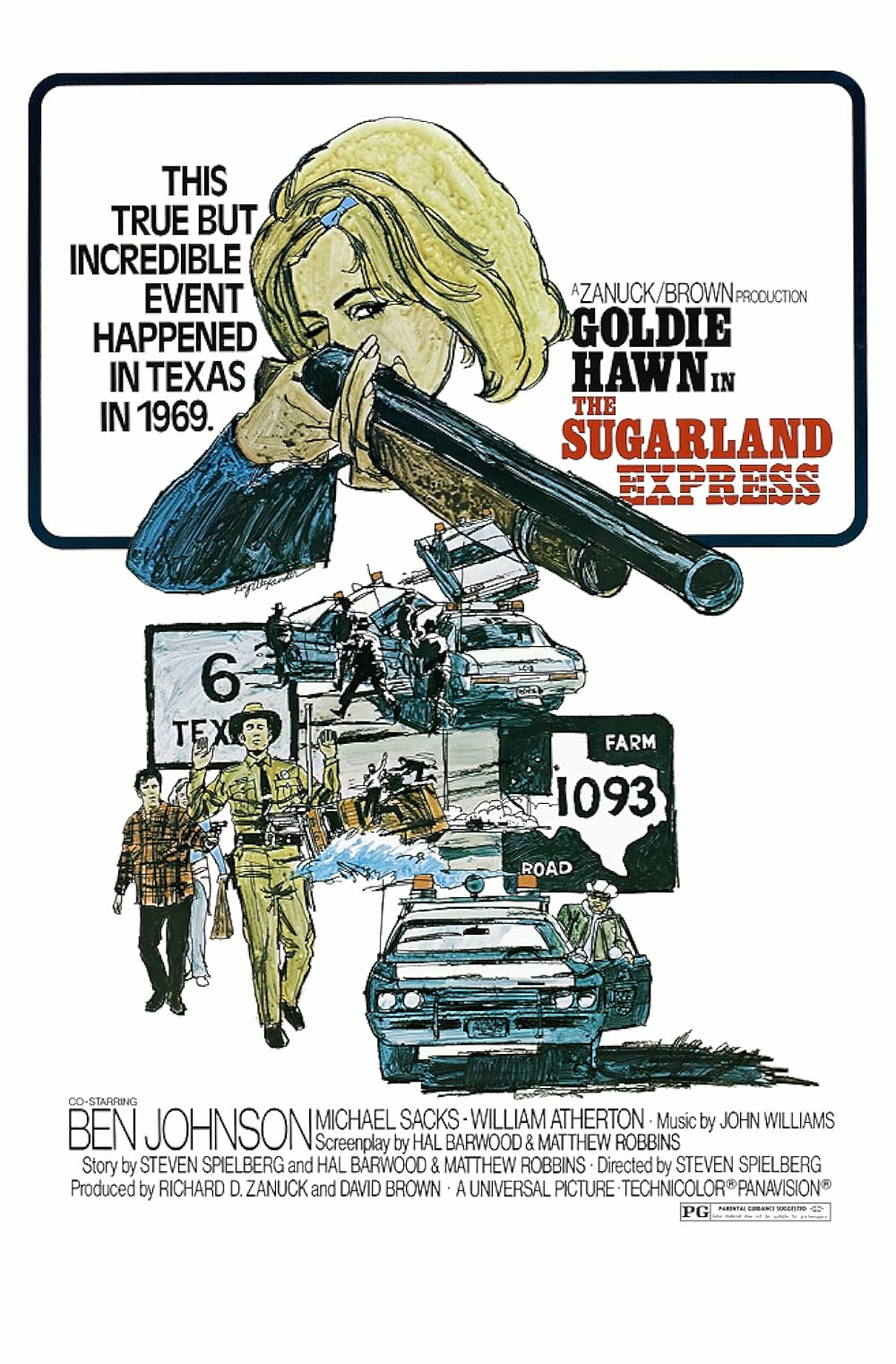

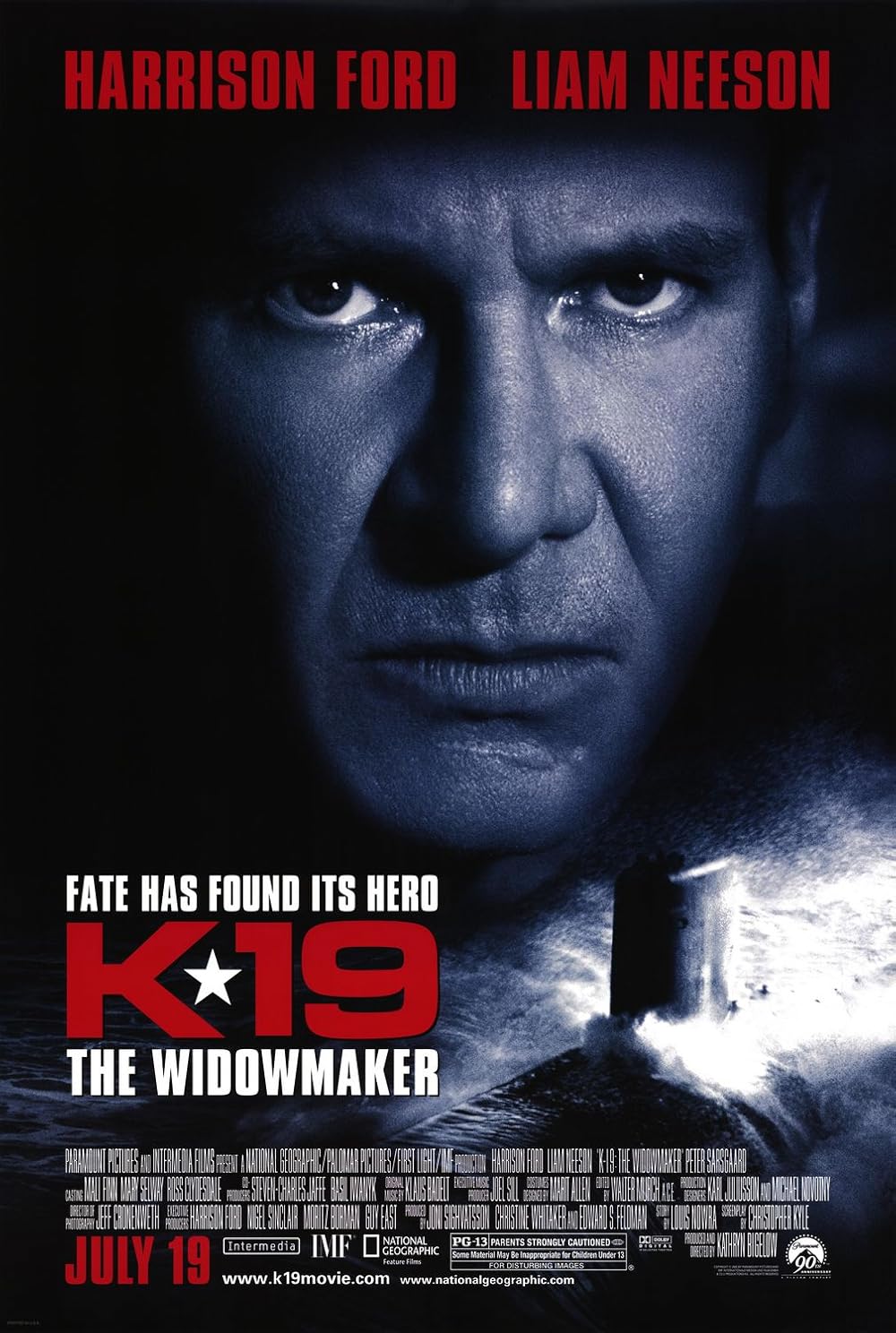

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

2027 Oscar Predictions: Jan.

Written Article - Todd |

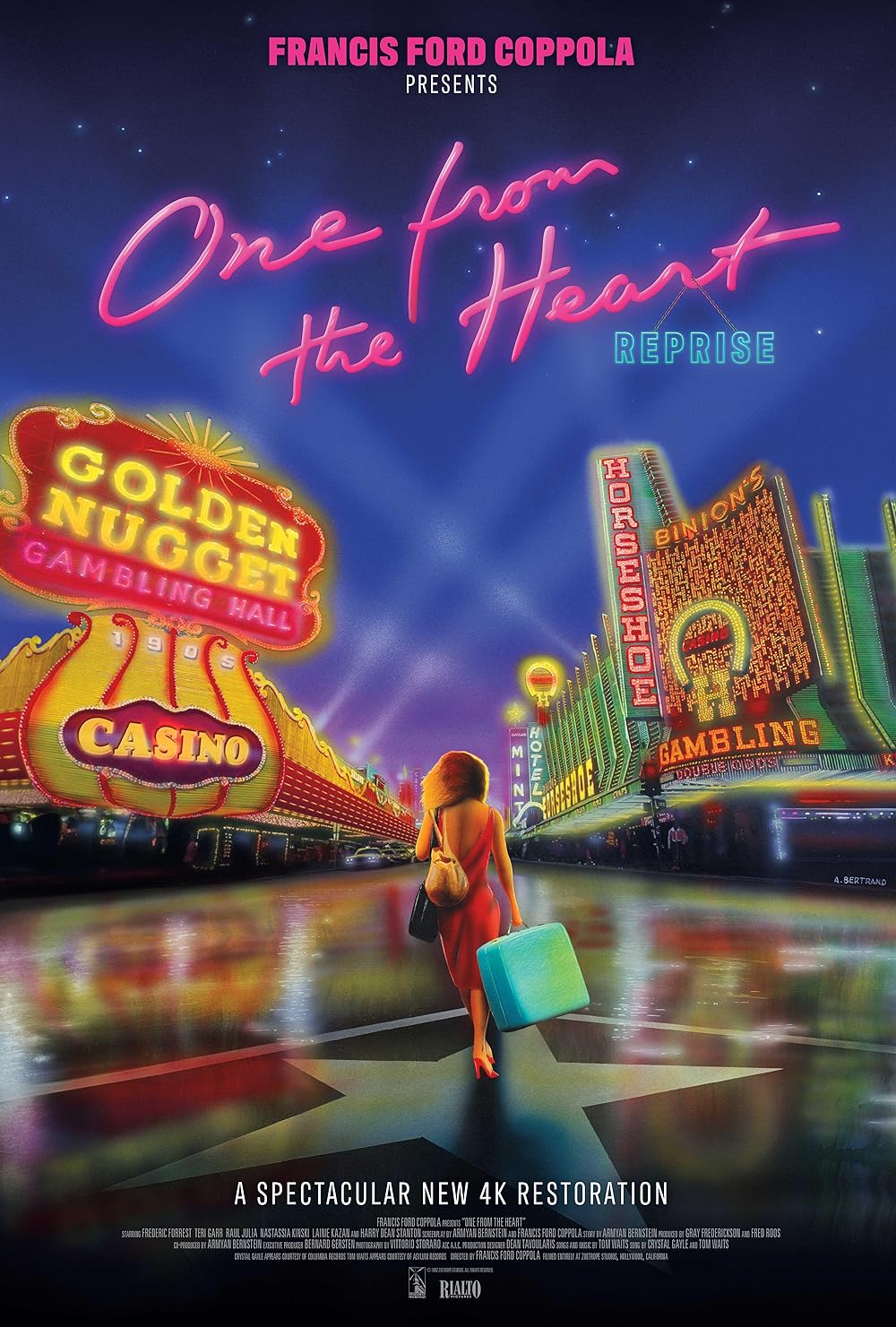

Terry Most Anticipated #2

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

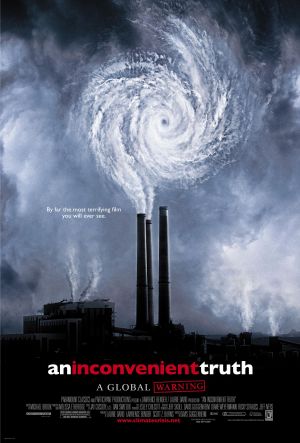

20th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Trivia Review - Adam |

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Terry |

25th Anniversary

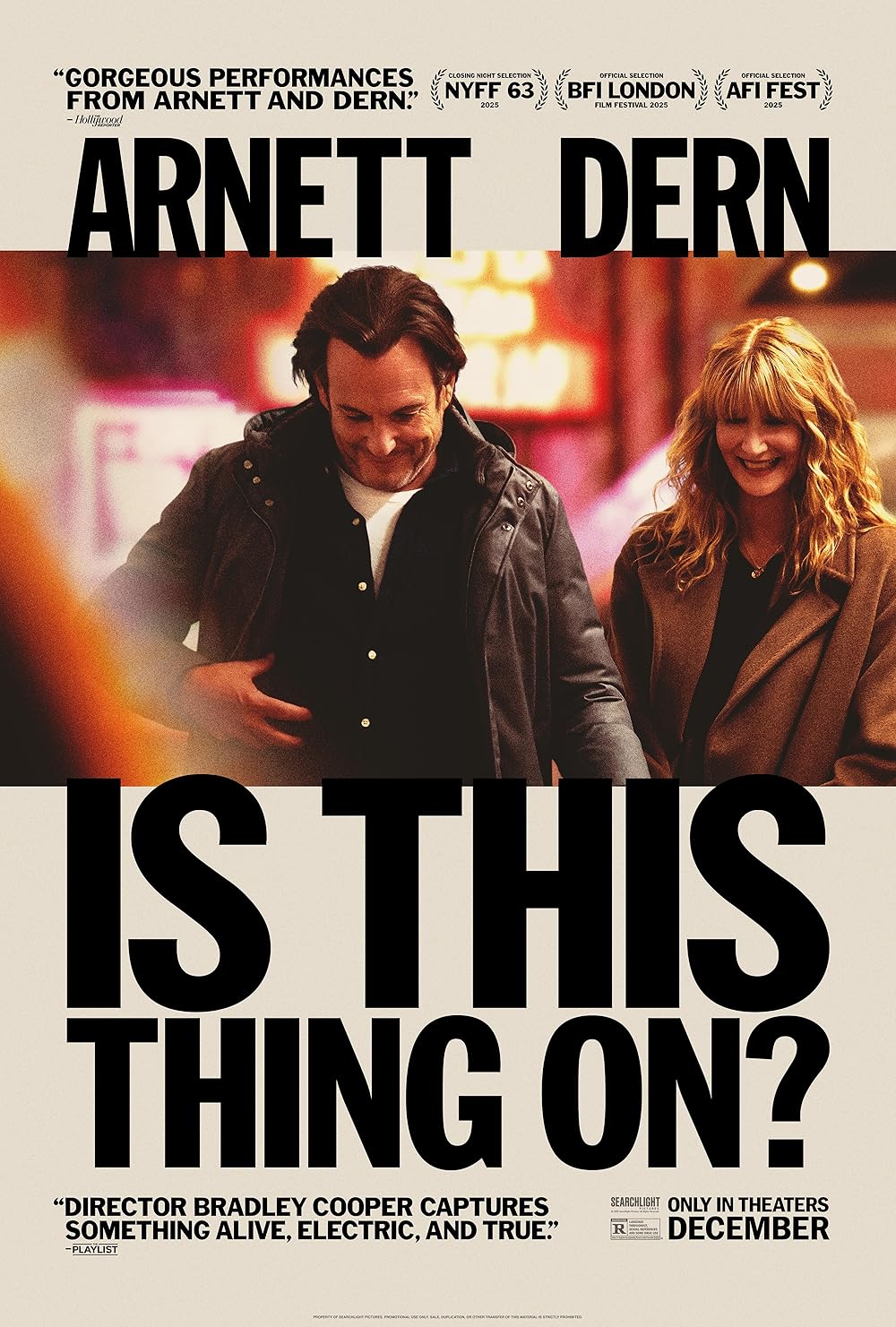

PODCAST DEEP DIVE |

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Indie Screener Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

|

|

|