|

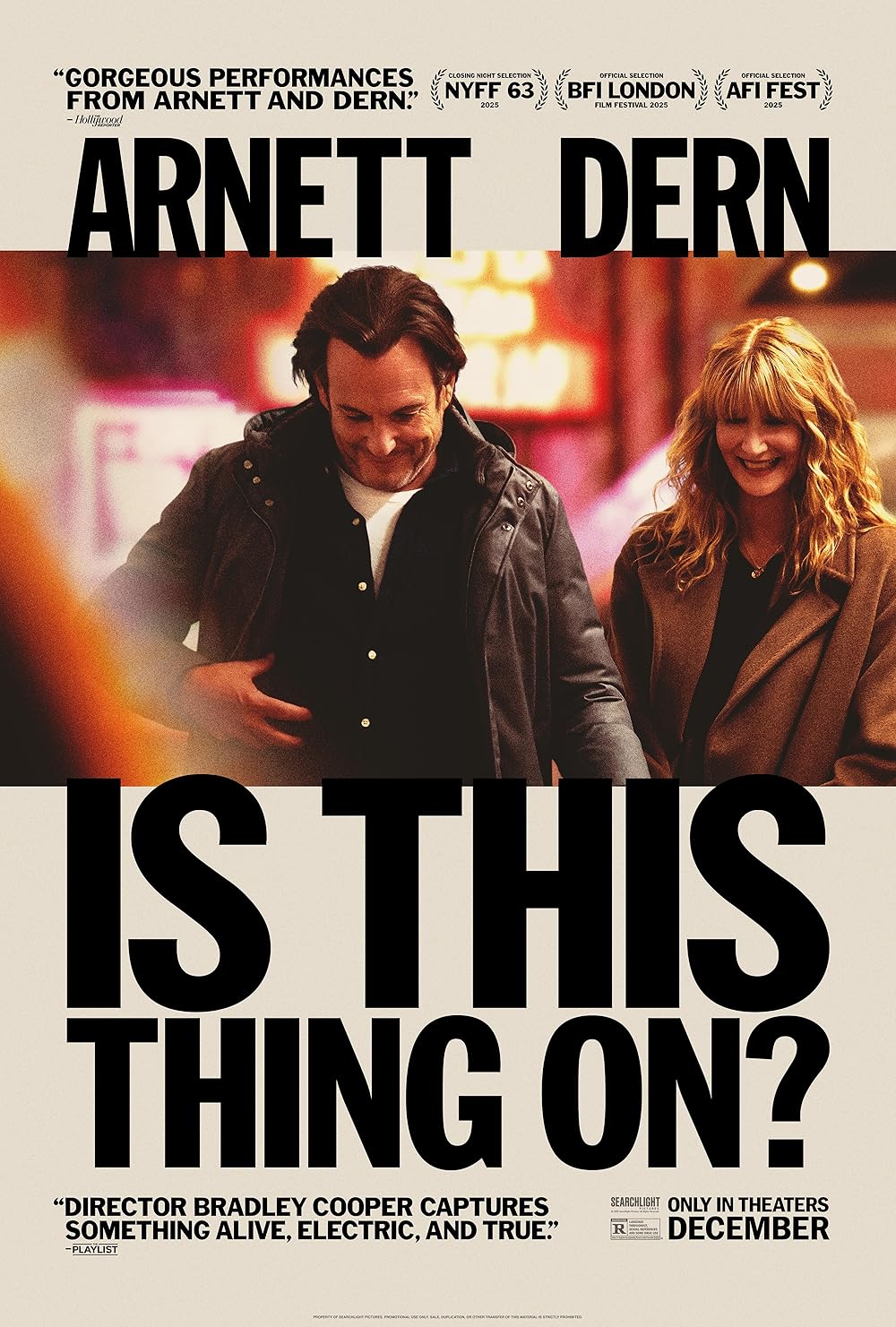

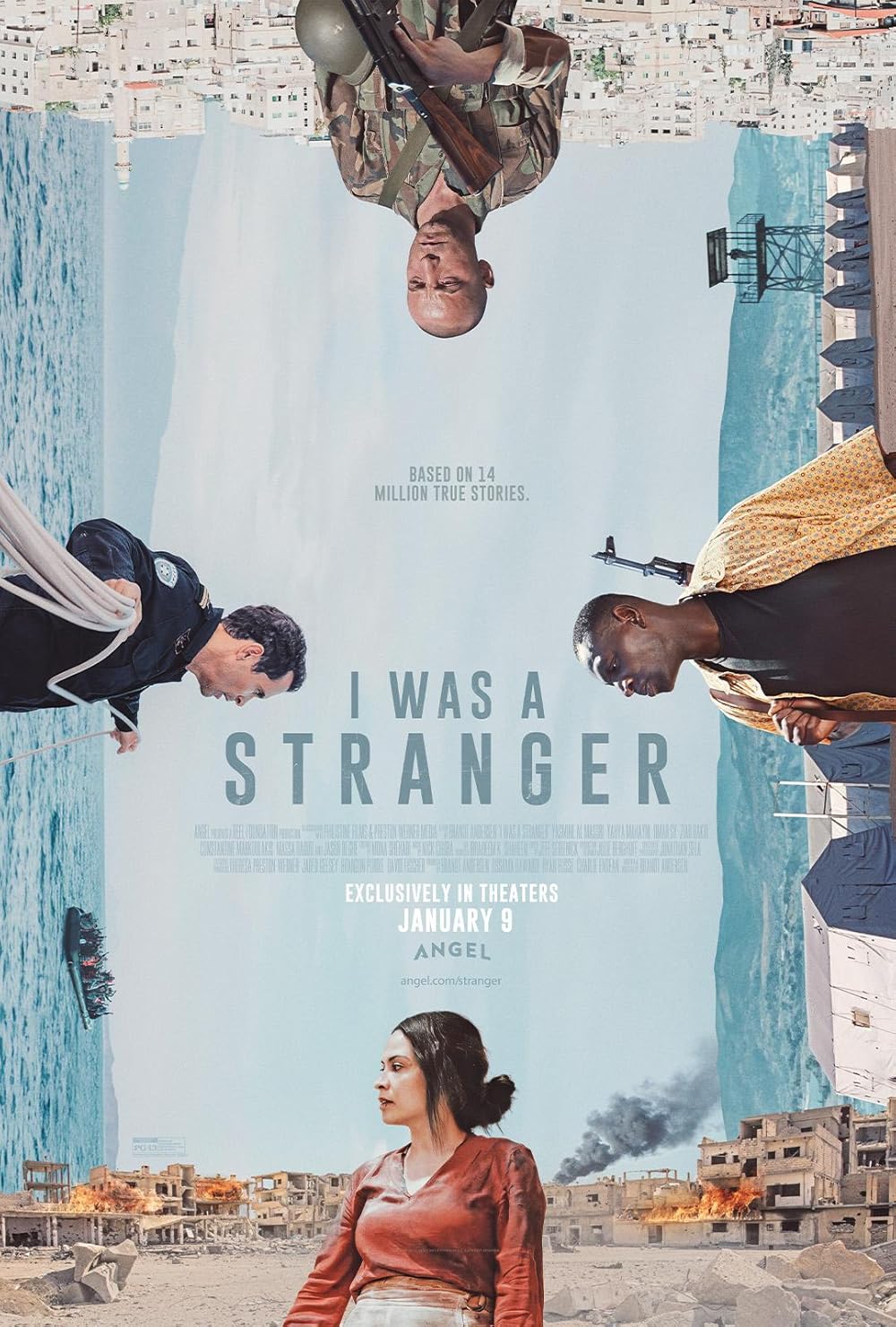

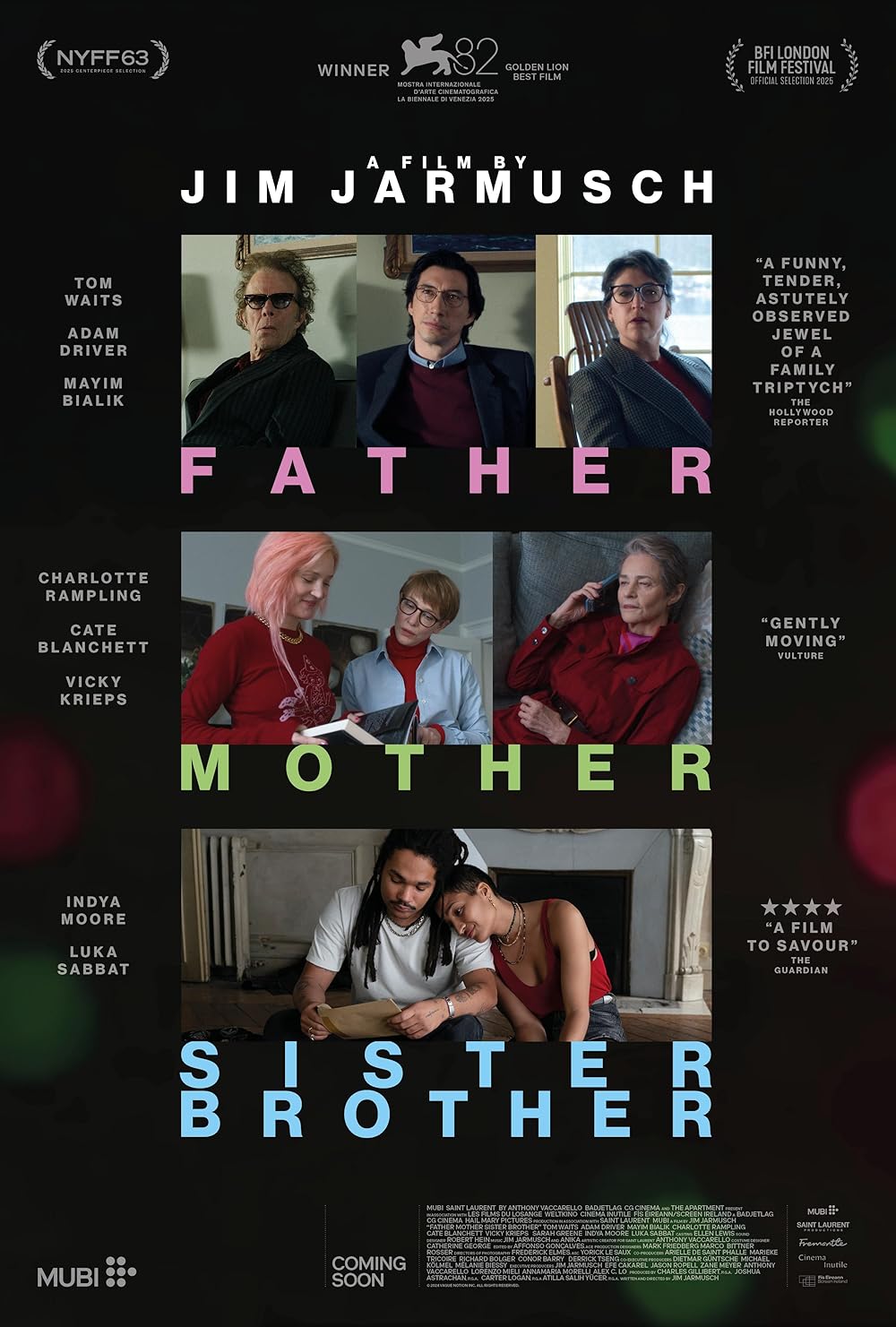

New

Releases |

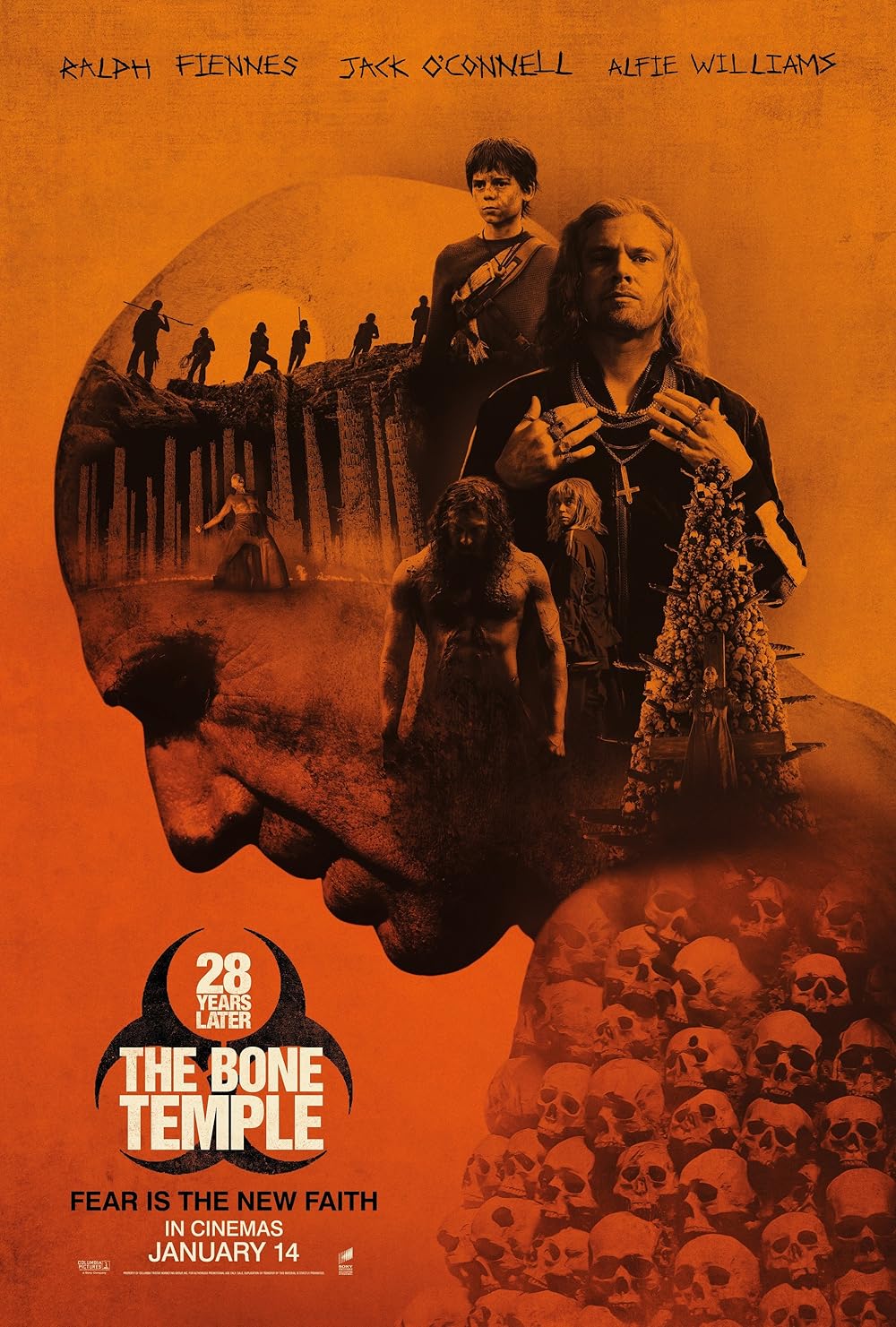

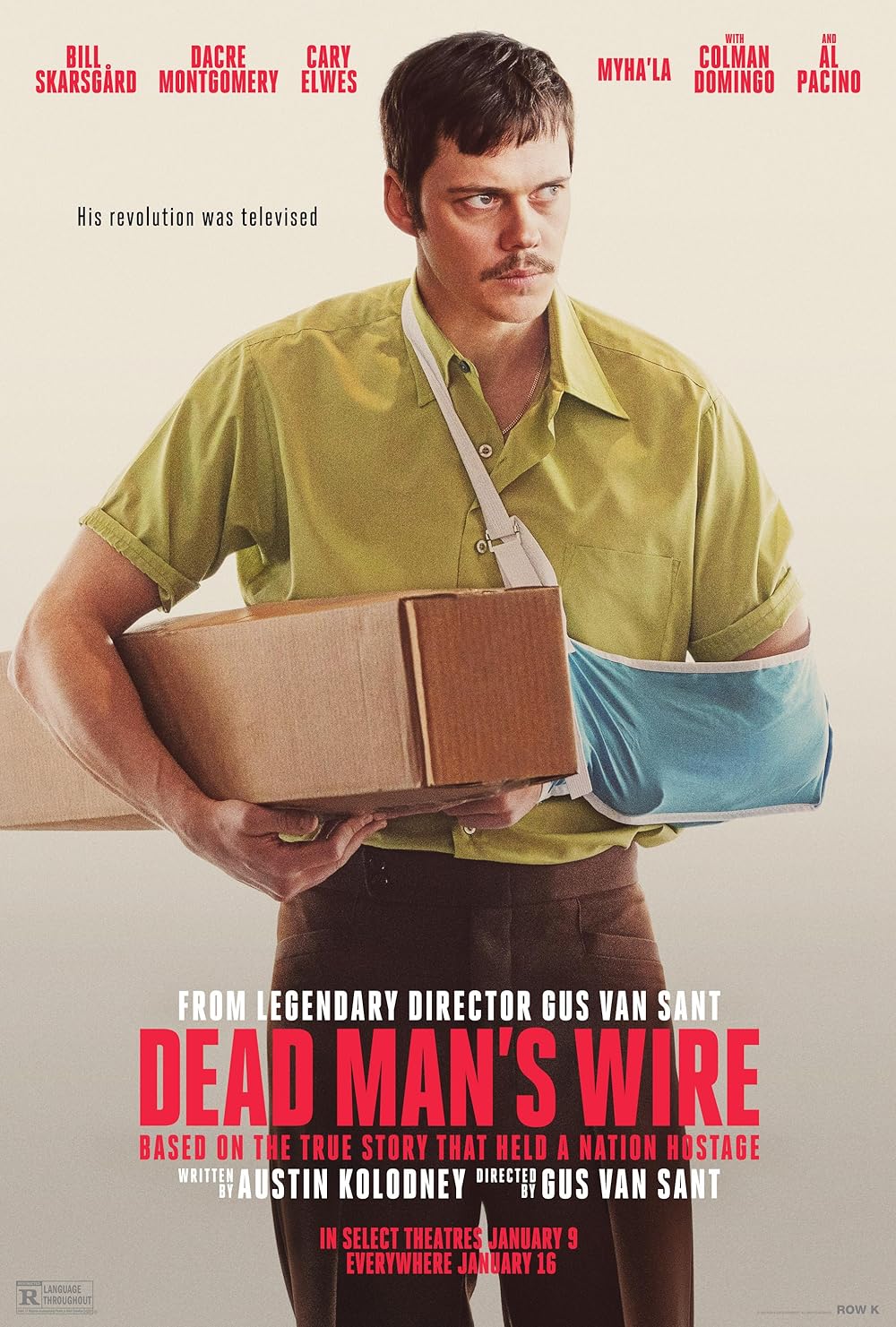

January 16, 2026

|

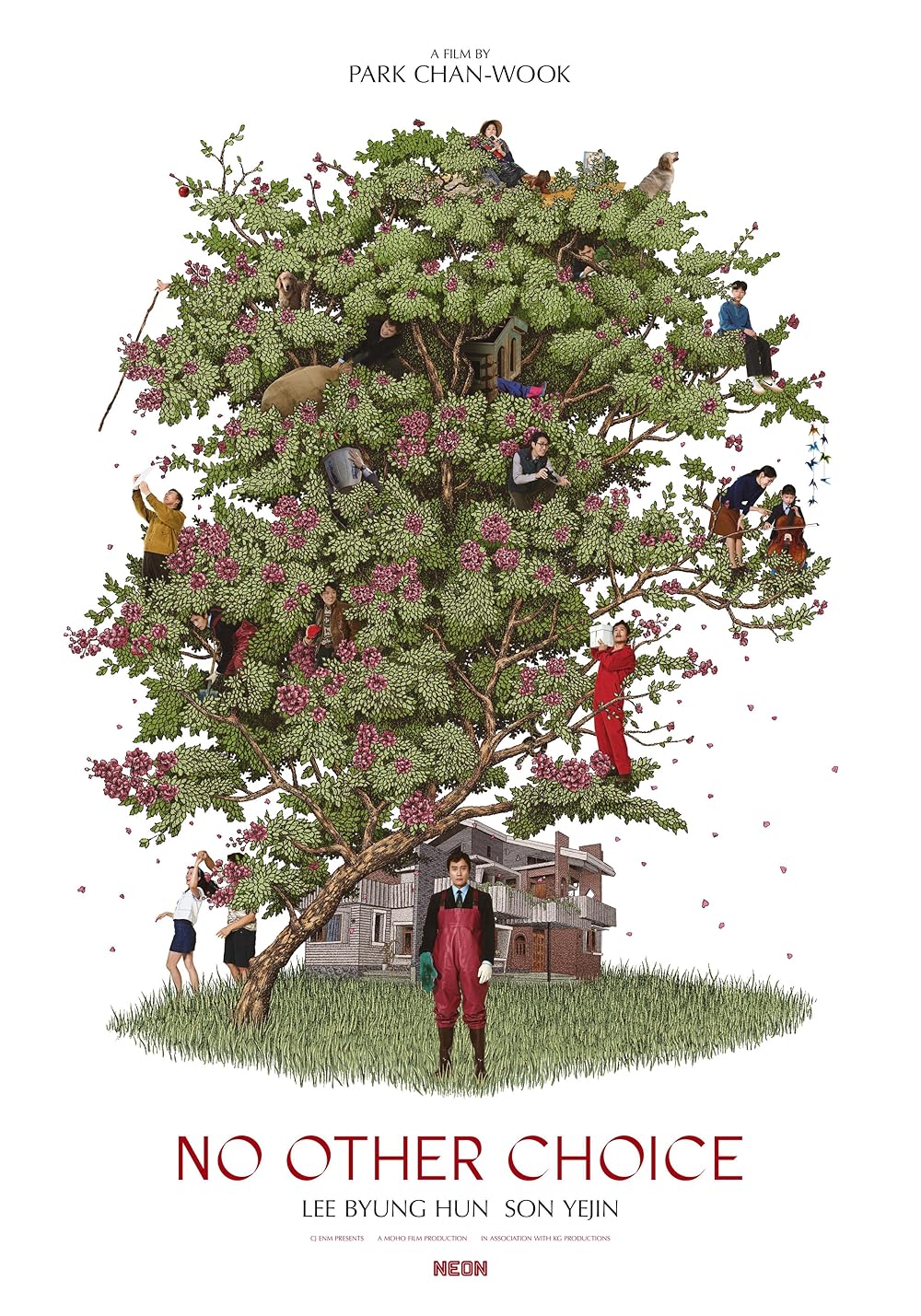

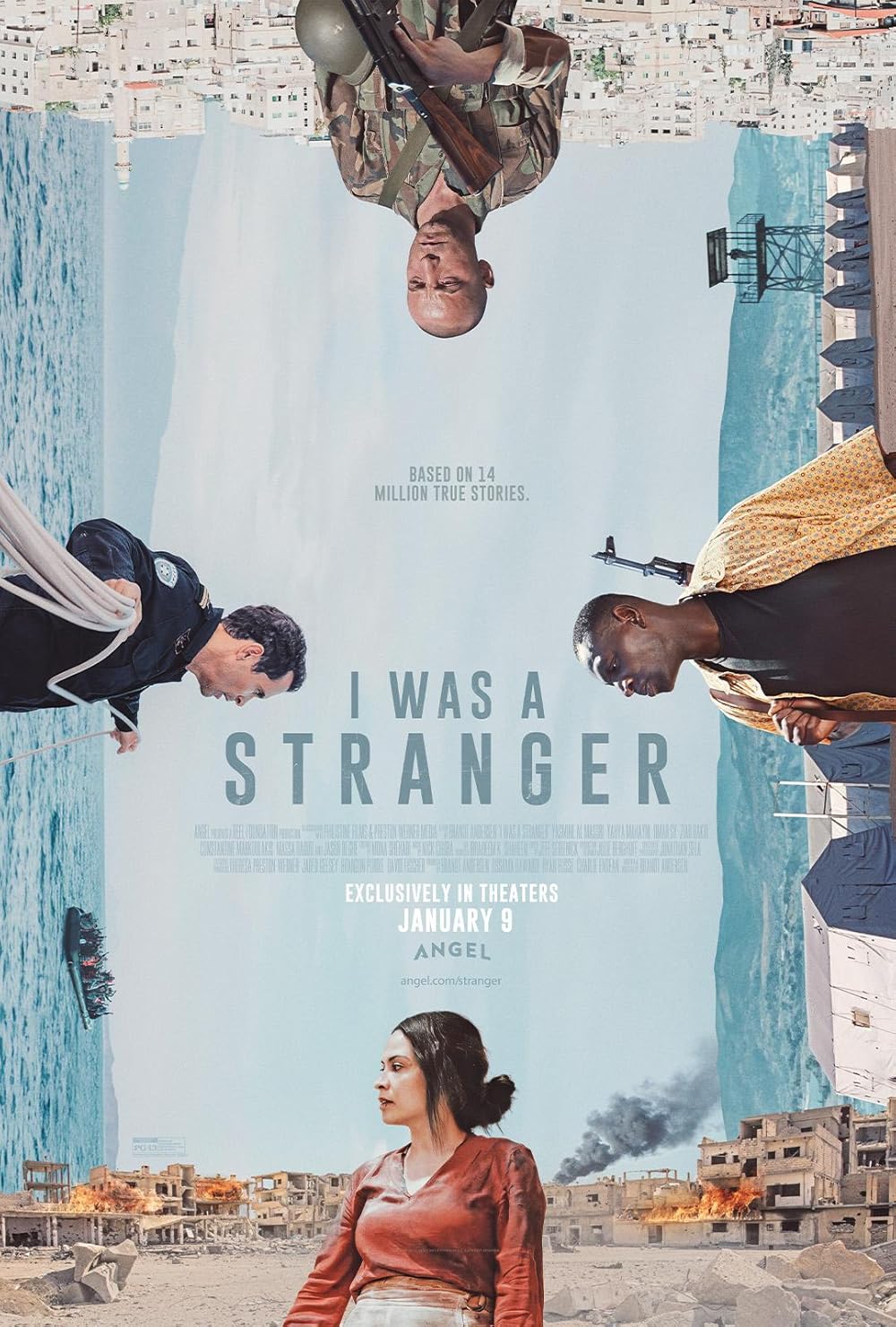

January 9, 2026

|

January 2, 2026

|

December 26, 2025

|

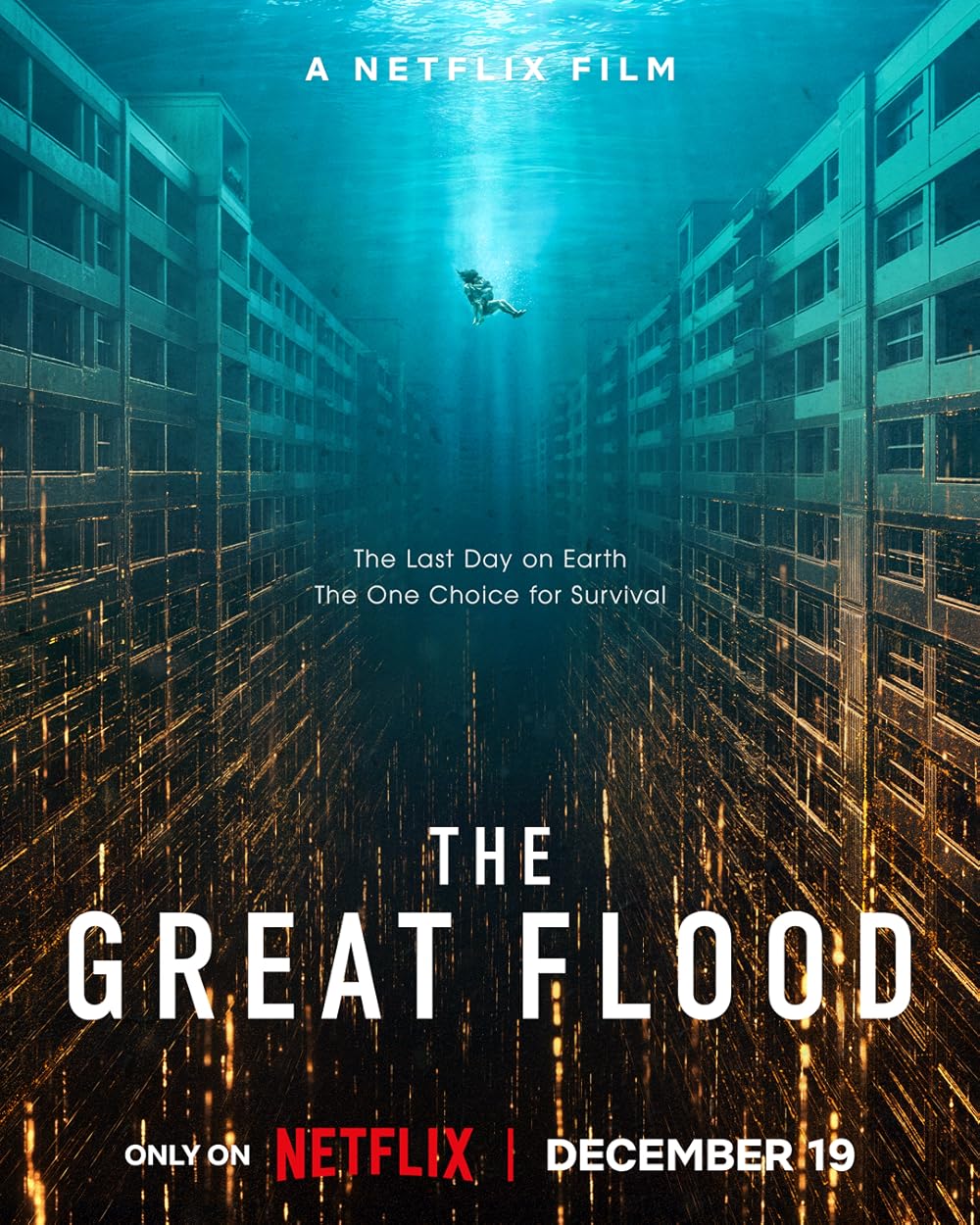

December 19, 2025

|

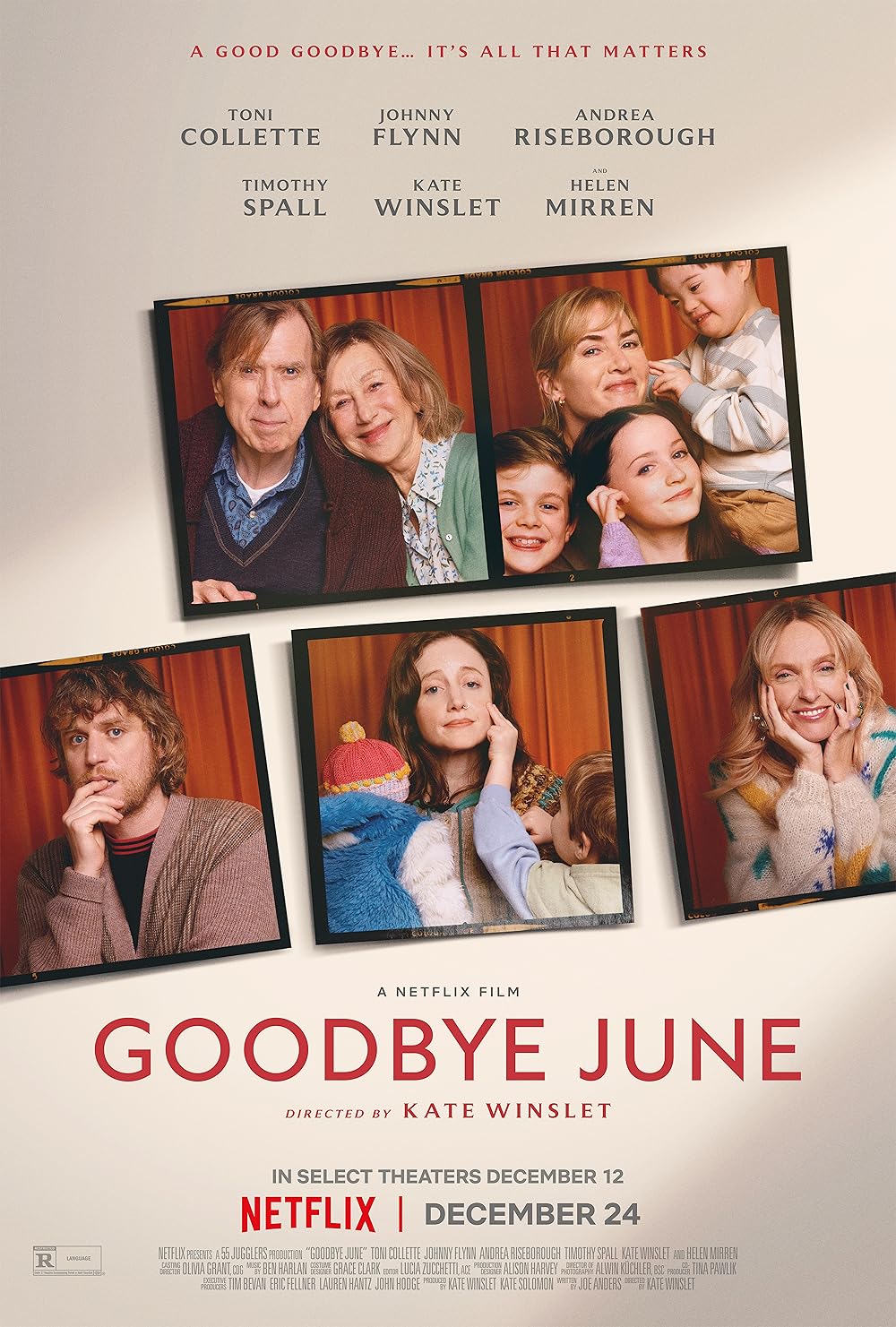

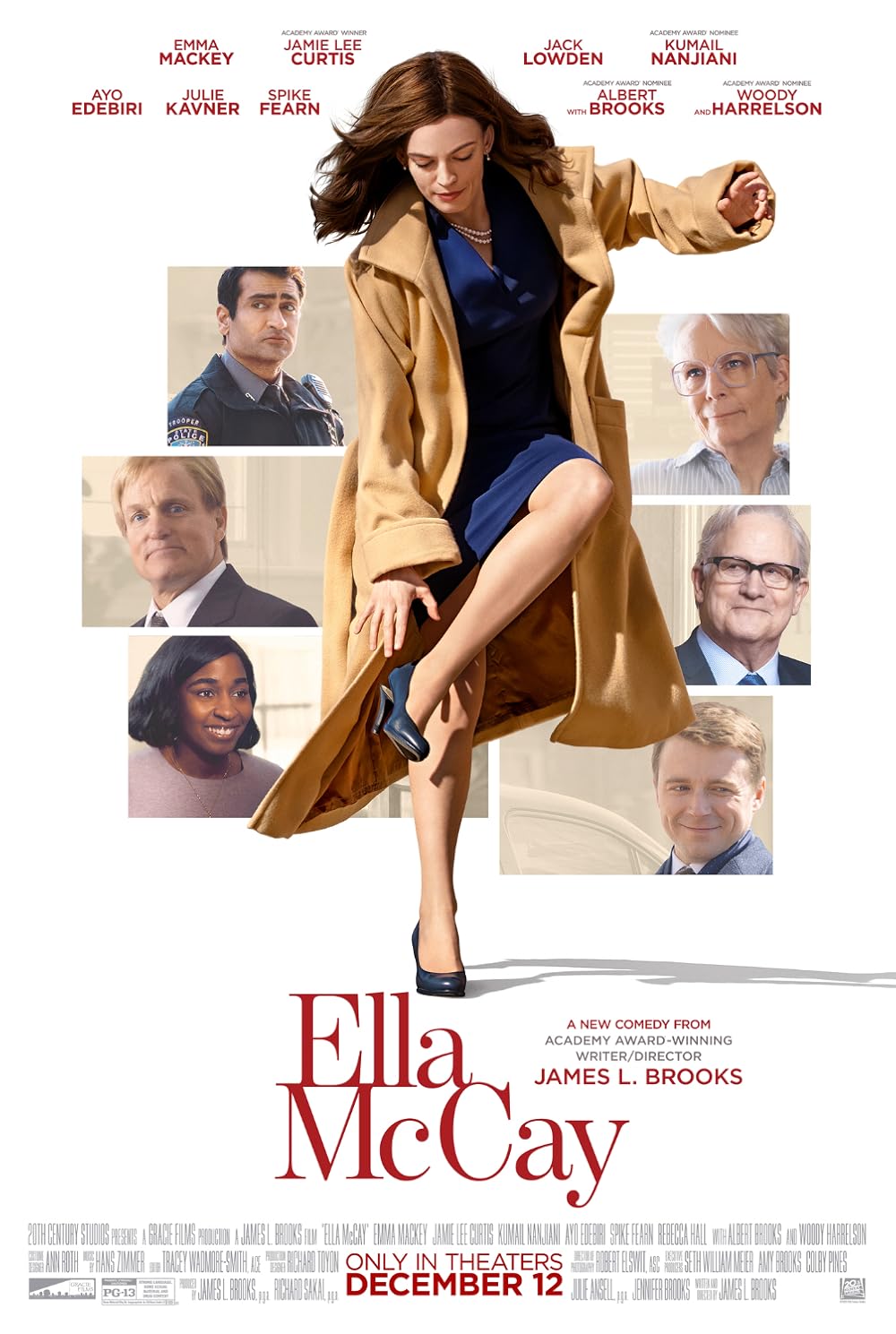

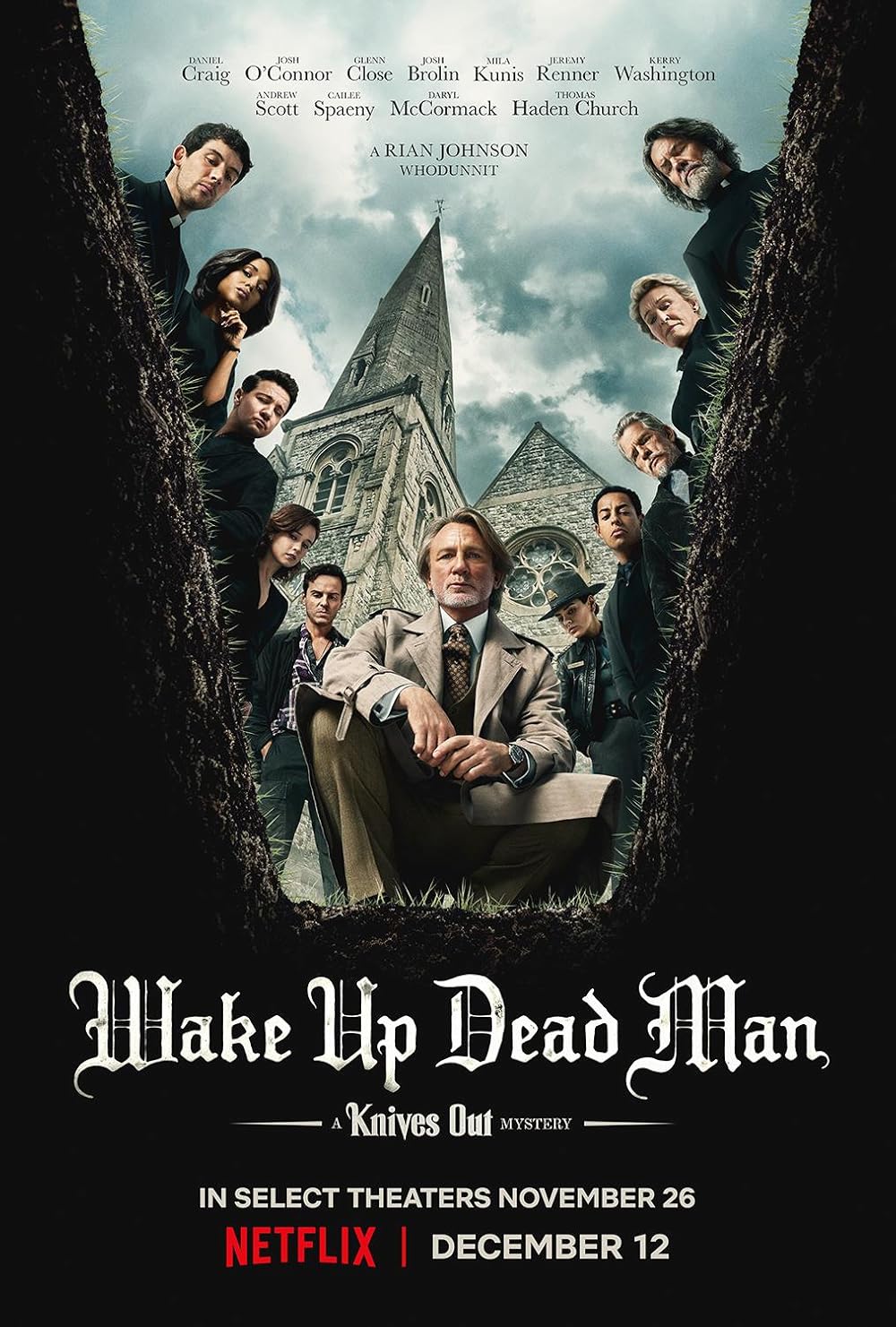

December 12, 2025

|

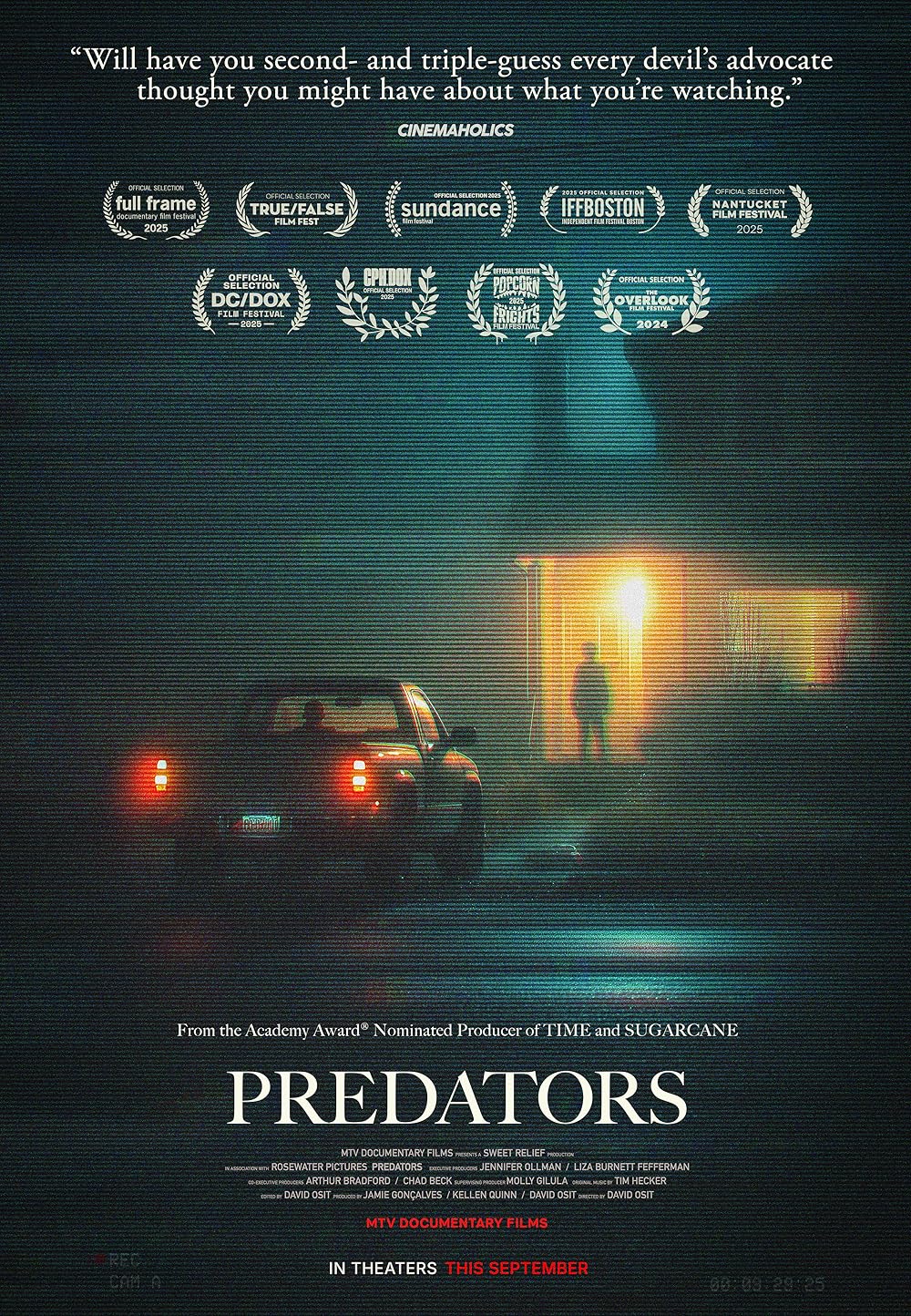

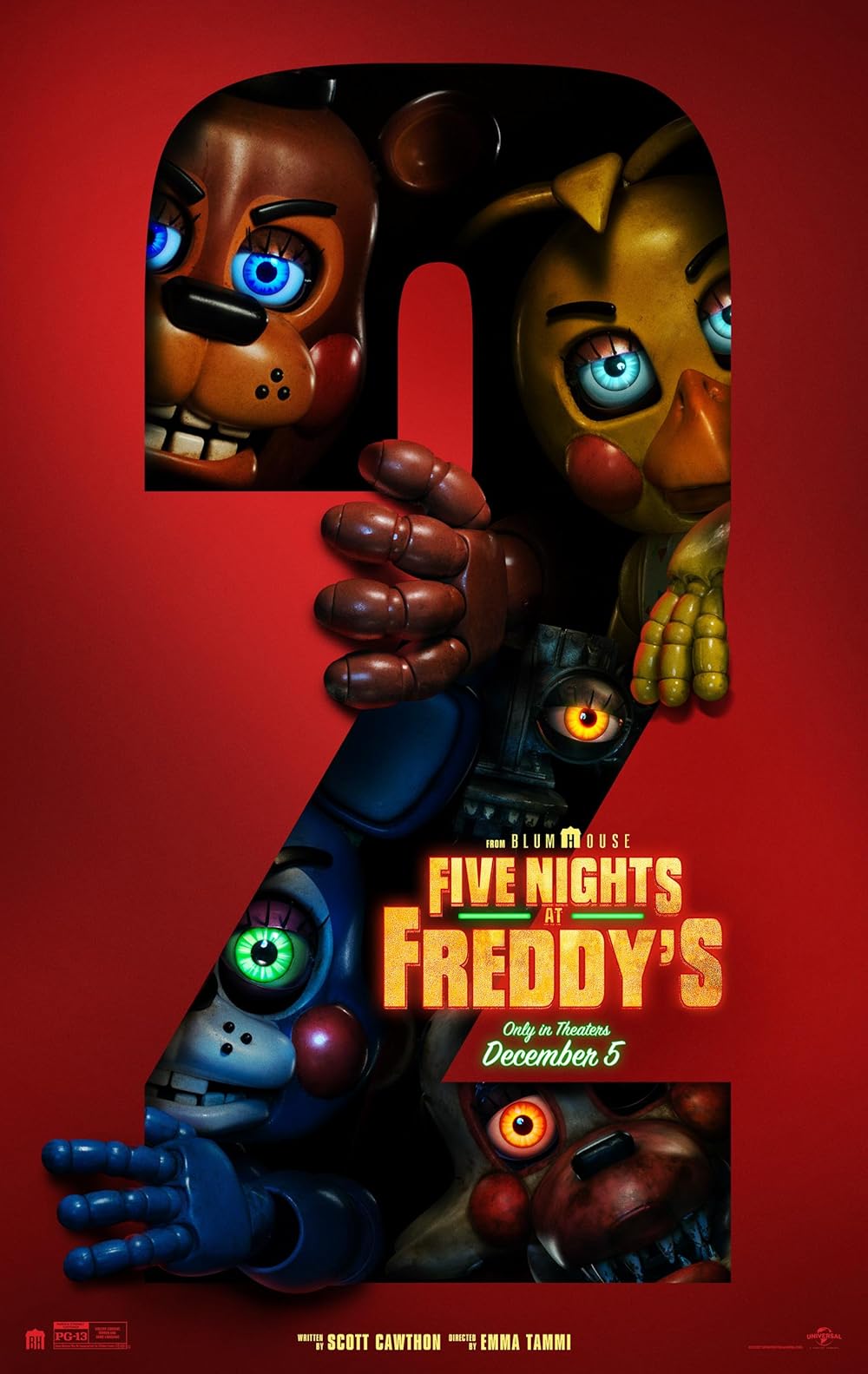

December 5, 2025

|

|

|

|

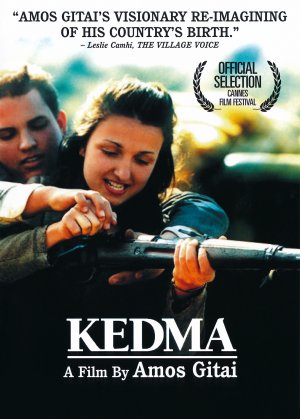

Kedma

(2002)

Directed by

Amos Gitai

Review by

Zach Saltz

Amos Gitai’s

Kedma (2002) begins with a women slowly and seductively removing

her top, and proceeding to fall on a bed where her husband makes

passionate love to her.

The

scene is unabashedly erotically-charged, as the camera casually and

voyeuristically intrudes on the couple’s quiet intimacy in apparent

isolation.

But after a few

moments, the husband, Janusz, inexplicably stops midway through, puts on

clothing, and walks away from his visibly distressed wife, only to

reveal a host of desolate onlookers, robed in dark, heavy clothing.

Janusz then climbs up a ladder and steps on the main deck of the

freighter the couple have been traveling aboard all along.

Contrasting the highly personal, serene lovemaking are images of

seasick passengers vomiting overboard, while others huddle together for

warmth amidst the cold ocean breeze.

Intimacy and comfort must be sacrificed for the sake of a dream.

These

onlookers are European Jews aboard the Kedma

(meaning “Toward the

Orient”), one of the many rusty old cargo freighters transporting its

displaced war-ravaged passengers to the Holy Land of Palestine. The date

is May 7, 1948 – only a handful of days before the independent Israeli

state will be declared, and the solemn faces of the

Kedma’s

passengers, a continental cross-section of concentration camp survivors,

illustrate an attitude that is hardly gleeful about the prospect of yet

another journey into diaspora as a result of persecution.

“I want to cry, I want my tears to reach the whole world,” a

sober chanteuse somberly sings to her fellow exiles.

Another man quietly asks: “If God loves us so much, where was He

when they were killing us in the camps?”

If there is any hope that Holocaust survivors can band together

and form their own autonomous state, it will rely on their ability to

unify through mutual grievance over the loss of their loved ones;

indeed, their conversations with one another are comprised squarely

personal accounts from the ghetto and the Eastern front (in one

revealing scene, a Russian asks a Pole what to shout in battle instead

of “Long live Stalin!”)

Once the

Jewish passengers reach land, they immediately encounter a band of

flag-waving British soldiers equipped with automatic weapons; the unit

is immediately overrun by Haganah units bringing the

Kedma

passengers to safety at the nearby Kibbutz.

By this time the British, sensing the growth of the Haganah after

their raids of Arab districts in Jerusalem (known as Plan D), had slowly

began to withdraw troops from fortified strongholds, “cleansing”

themselves of the imminent bloodshed that was sure to ensue from the

Arabs and the Jews.

But

Gitai is careful in assessing their assumed bloodthirsty hostilities;

indeed, the central scene of the film occurs when a group of lost Jews

encounter a band of Arabs on horseback who have been driven out of the

region.

Klibanov, the

navigator, asks an Arab woman at the head of the pack from whom the

group is fleeing.

“The

Jews,” she replies, “and who are you fleeing from?”

“The British,” solemnly replies Klibanov.

It does not take long for the Arabs to realize that they have

encountered the very people responsible for their mandatory departure,

and it appears that a skirmish has begun – until both sides, exhausted

from traveling, simply give up and let each other pass.

Fatigue, piety, and resentment toward foreign invaders may be

perhaps the only two things the Arabs and the

Kedma Jews share,

but both are powerful forces in mobilizing support for each side’s

mission to peaceably inhabit the Holy Land.

Sadly and

inevitably, however, the mutual desire for peace is not long-lasting,

and the Jews’ desire for arable land and sustenance is overtaken by a

desire to fight for that land – not merely to assert their control of

it, but to legitimize their claim to it as a result of their perceived

superior ethnicity.

“I

hunger not for bread, nor thirst for water, but to see your bodies

riddled with bullets,” a young man named Menahem valiantly proclaims

regarding the Arabs.

It is

in this virulent capacity for fighting that writer-director Gitai makes

a critical judgment toward the Jews; “if you want to live, you must

forget,” one refugee says of the Holocaust, “and if you want to survive,

you must forget.”

But while

the painful memories of the bloodshed of family members lost to vicious

Nazis occupies a central place in the minds of the

Kedma Jews,

they appear to have conveniently forgotten the torment of seeing their

own ghettos overrun with soldiers executing men, women, and children at

will – which is precisely what the Haganah units do without guilt to

local Arab villages and evacuees.

Indeed, a

question one must ask when viewing a story involving Arab-Israeli

relations is whether its author creates a fair and balanced perspective

on both sides; Amos Gitai appears to accomplish this balance extremely

well.

The viewer does

sympathize with the Kedma

Jews as a result of their plight from

Europe, but perhaps not so much with their actions.

Crucially, however, the director also includes a scene of

truculent Jews bullying a hapless elder Arab couple and confiscating

their mule to carry a dead body.

“We’re not trained like you, we’re not organized,” the old man

shouts, as he is abandoned in the middle of a battlefield.

Some critics, such as J. Hoberman, have called the episodic and

polemic nature of Kedma “less a movie than a symptom inviting

diagnosis”; but this is precisely Gitai’s point with his emphasis on

long, expressive shots of empty land, suggesting that true possession of

Israel was as vague and vacant in 1948 as it is today.

Rating:

|

|

New

Reviews |

Reactions to the Nominations

Written Article - Todd |

2026 Oscar Predictions: Final

Written Article - Todd |

Todd Most Anticipated #5

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

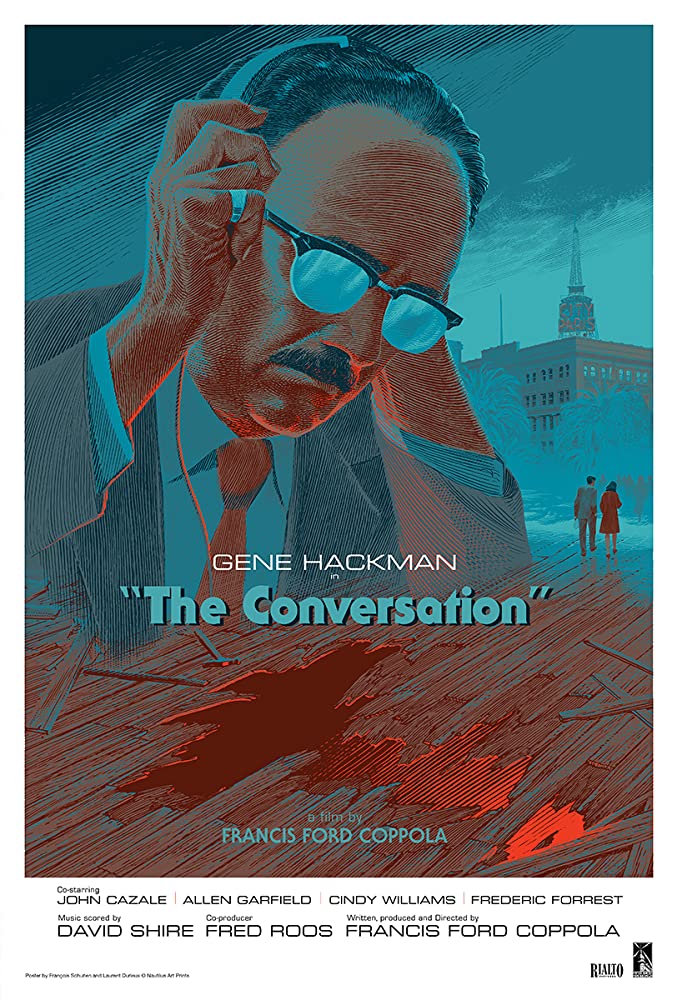

10th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Zach |

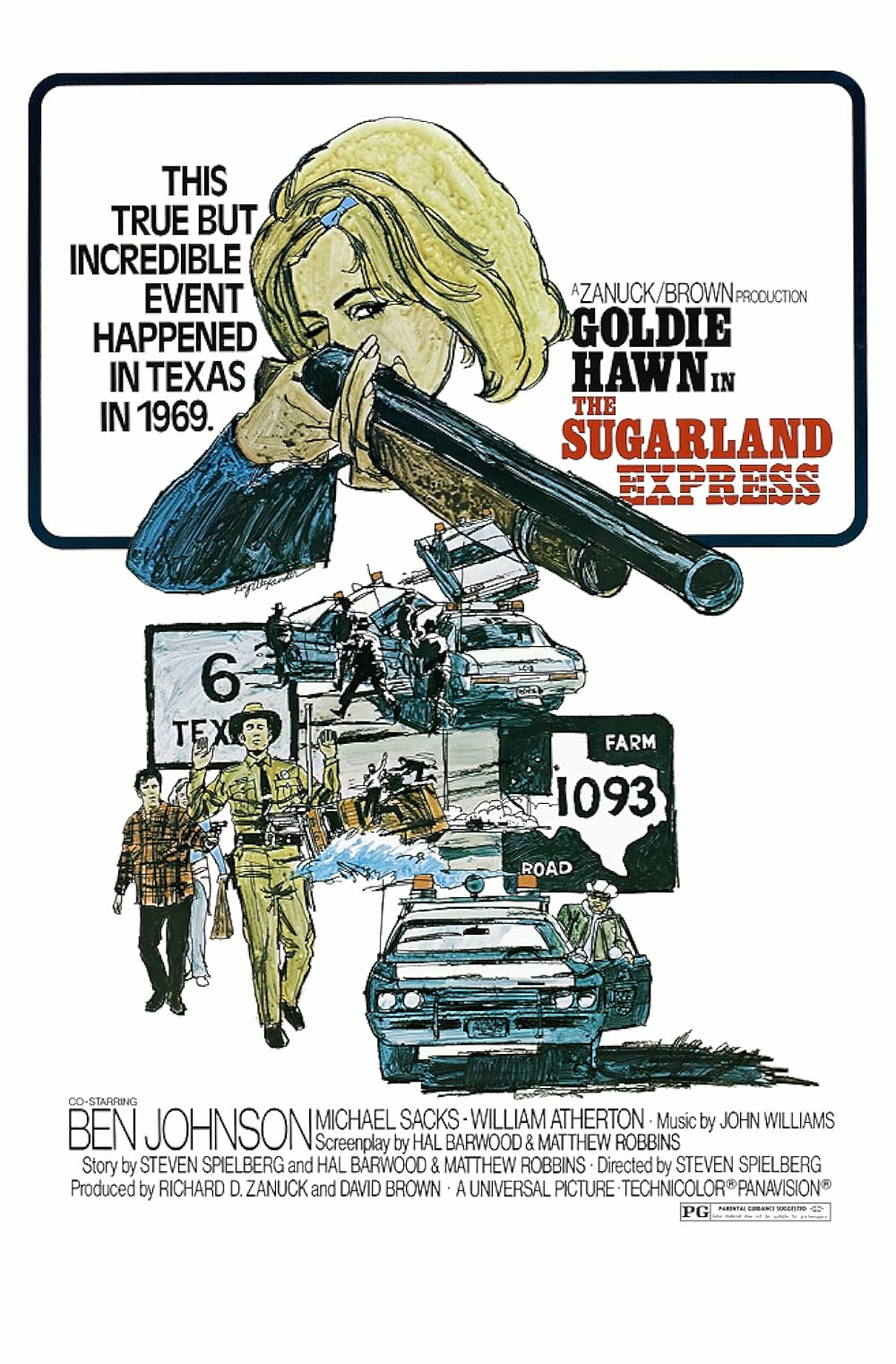

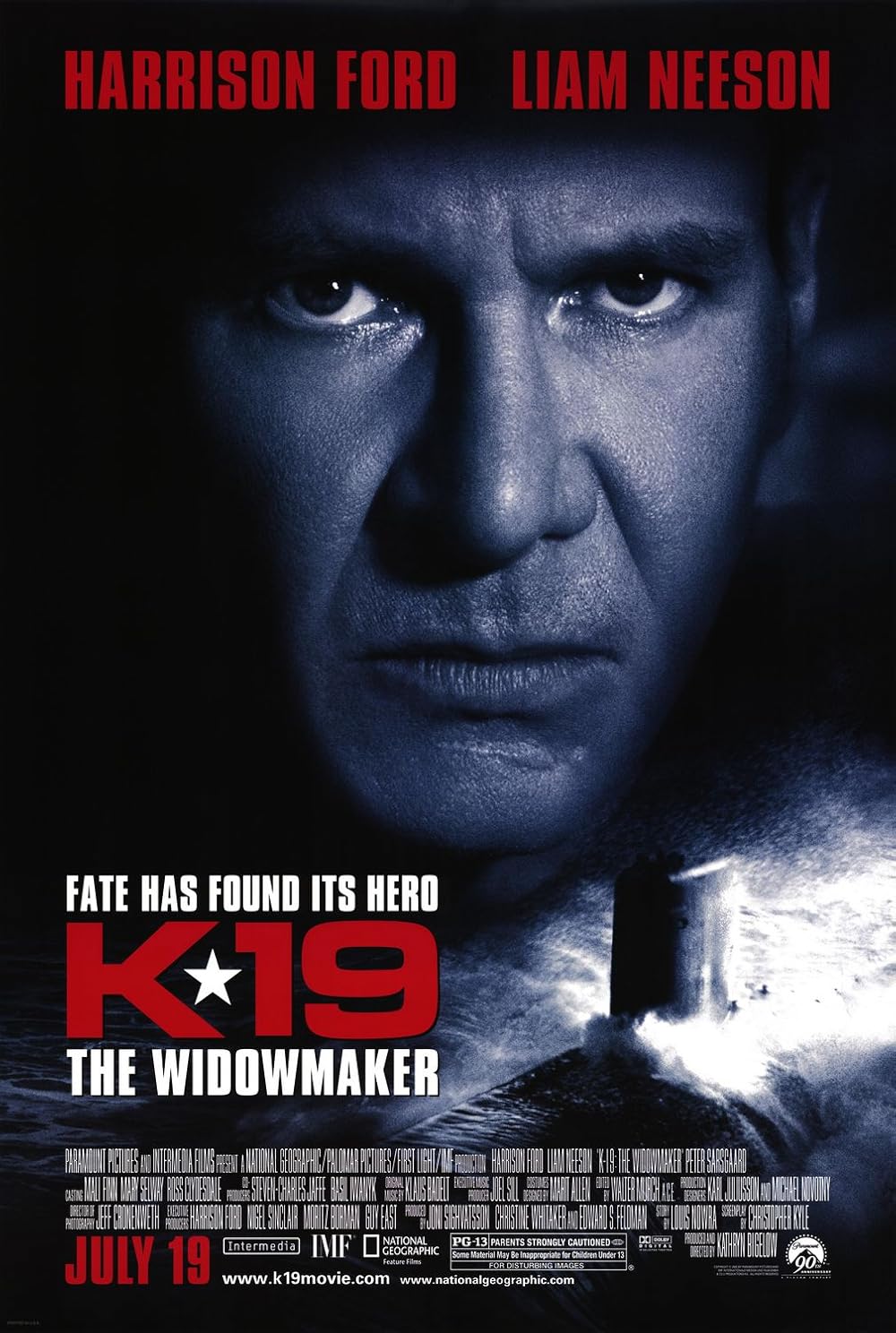

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

2027 Oscar Predictions: Jan.

Written Article - Todd |

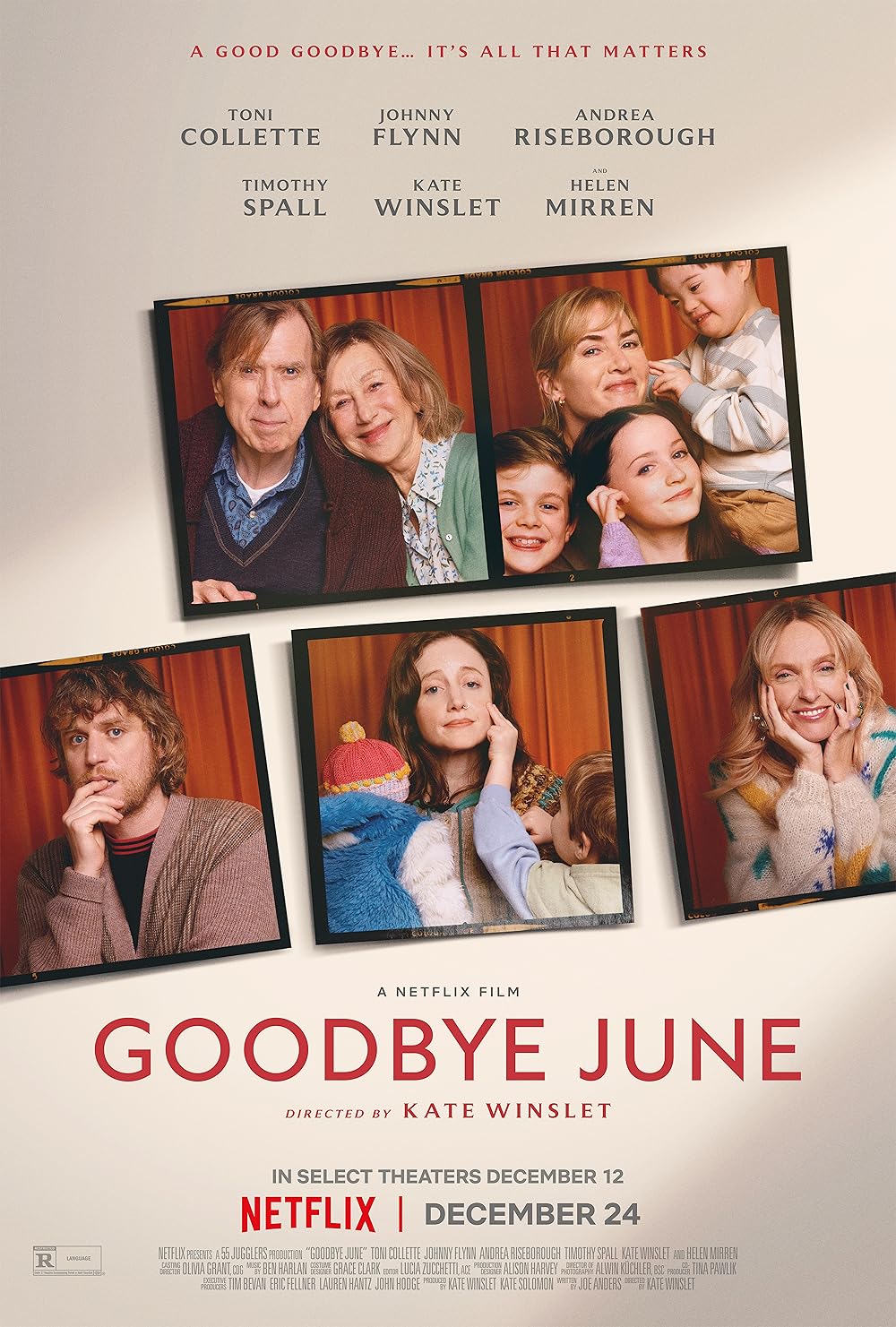

Terry Most Anticipated #2

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

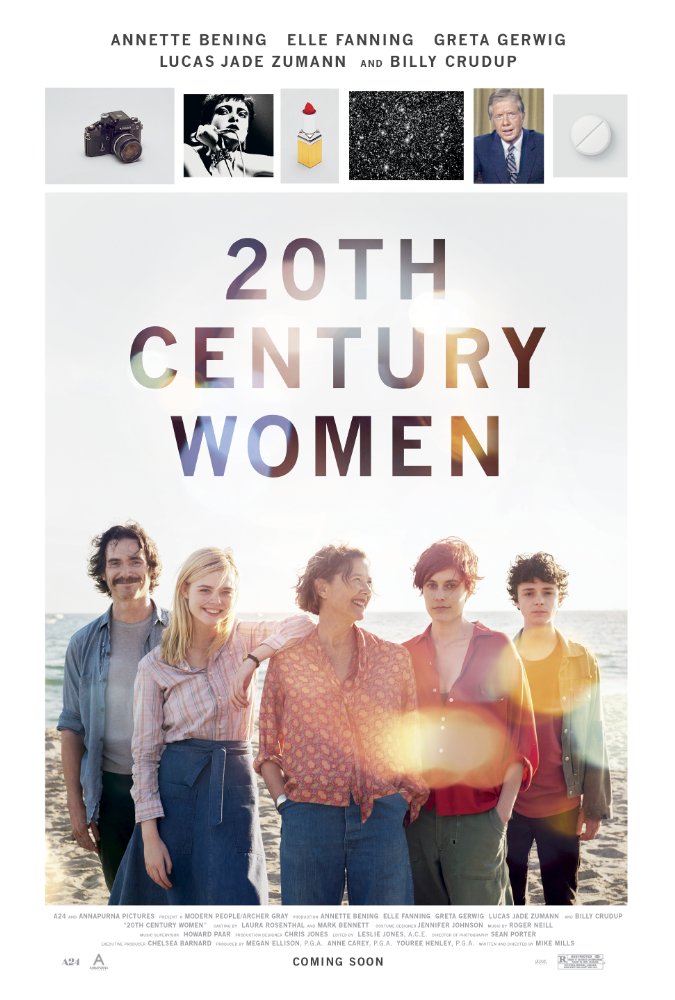

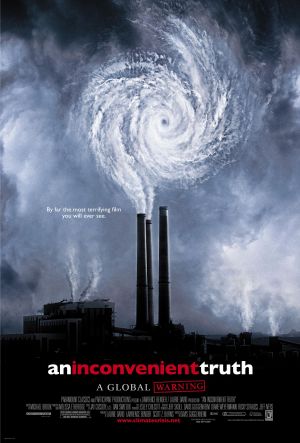

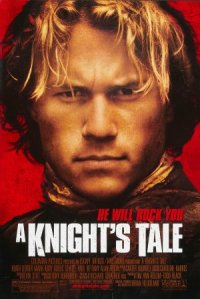

20th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Trivia Review - Adam |

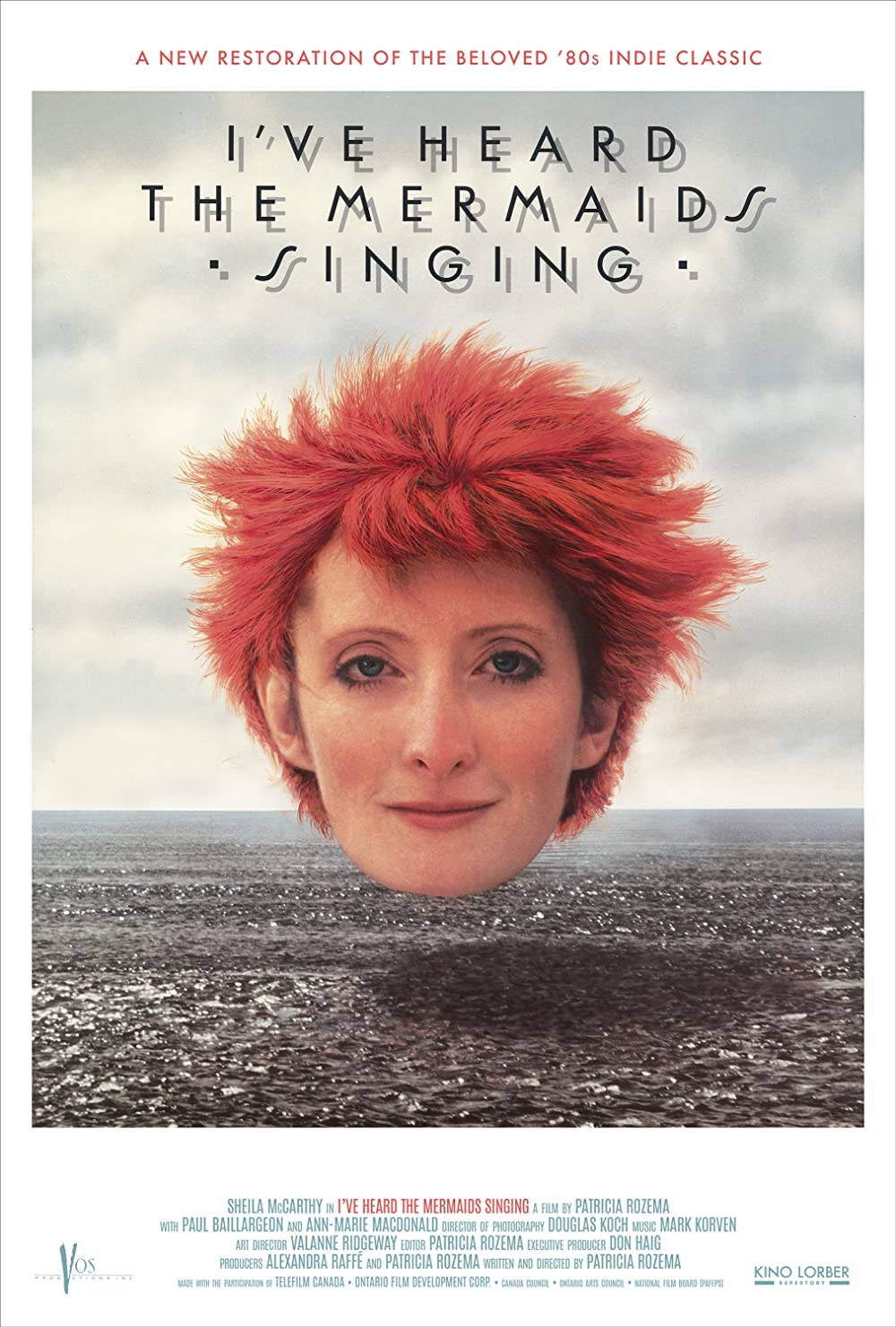

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Terry |

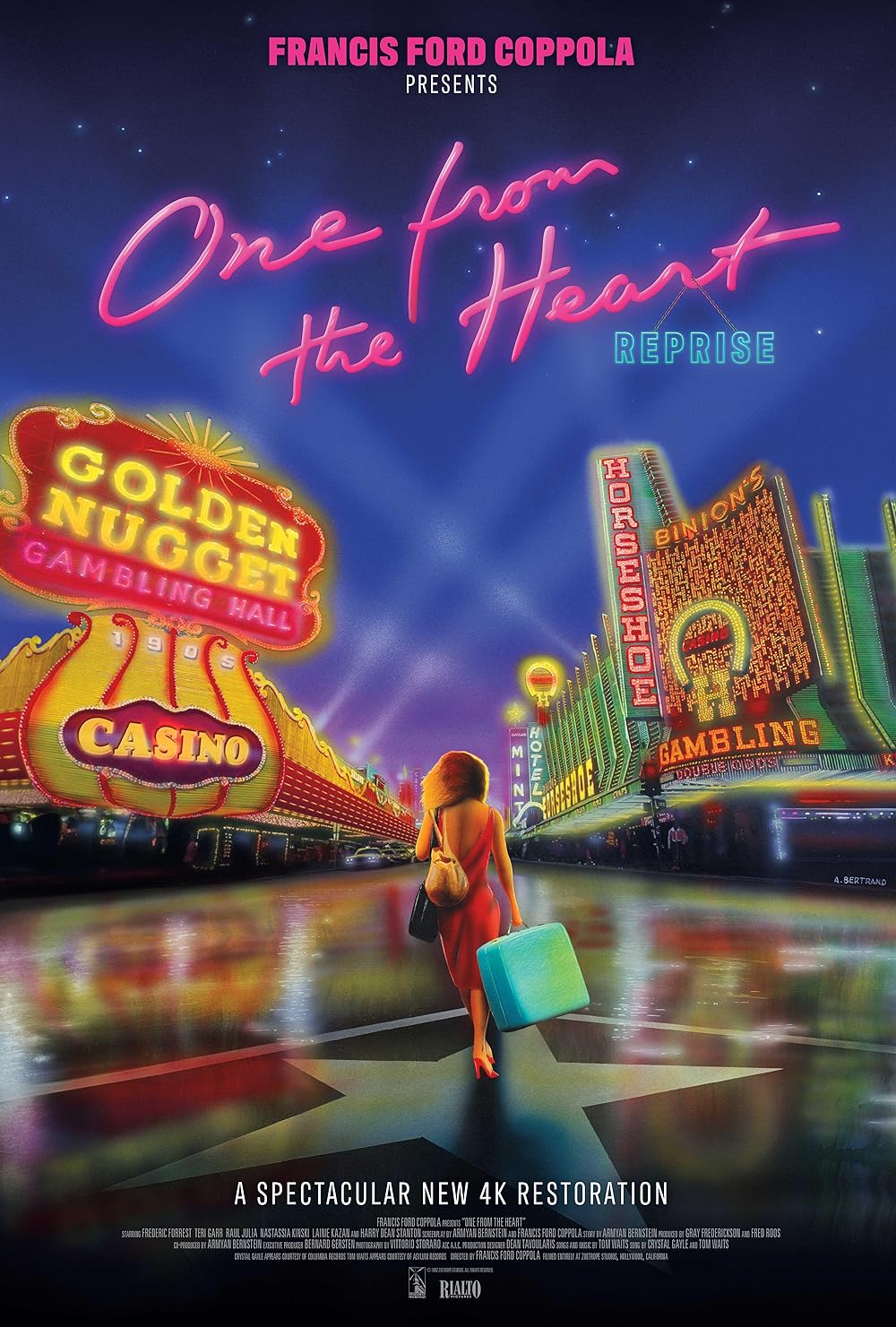

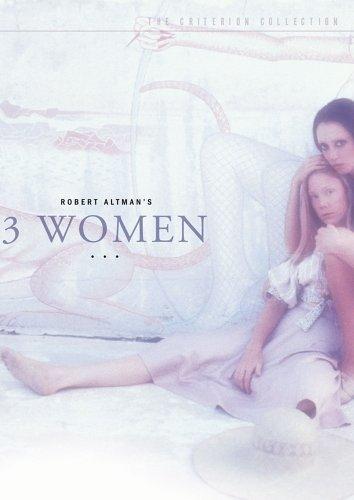

25th Anniversary

PODCAST DEEP DIVE |

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Terry |

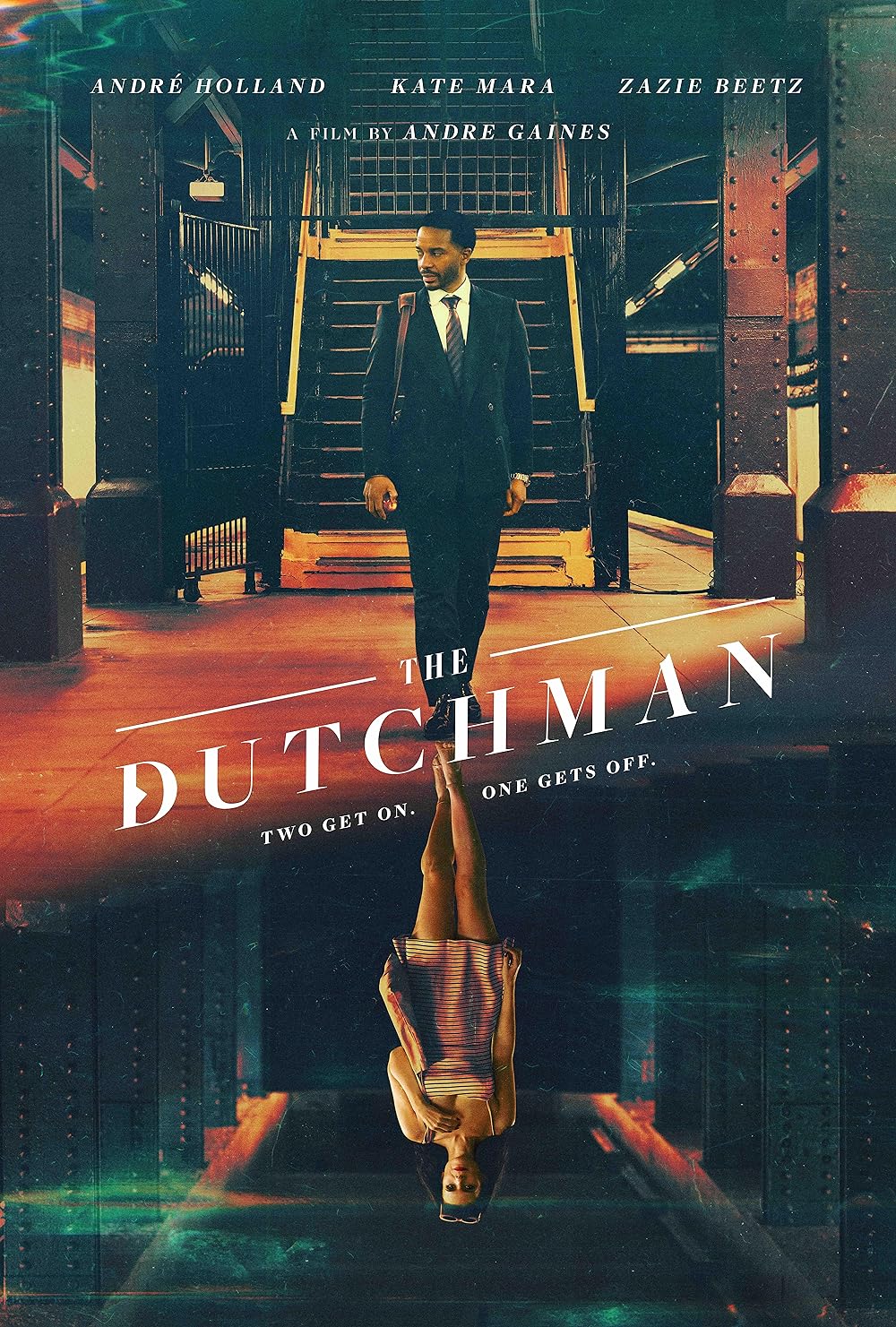

Indie Screener Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

|

|

|